A new study from Imperial College London reveals how “pirate” bacteriophages can hijack other viruses, infect bacteria and combat drug-resistant infections.

Bacteriophages hijack other viruses and invade bacterial cells and spread. This is a process that may be available for medical use in the treatment of drug-resistant infections.

This finding reveals an interesting novel mechanism by which bacteria acquire new genetic material, including properties that may result in bacteria becoming more pathogenic or more resistant to antibiotics.

However, researchers believe that these pirate phages will pave new avenues in tackling the development of antibiotic resistance global health threats and rapid diagnostic tools.

What is a bacteriophage? And how does it affect other viruses?

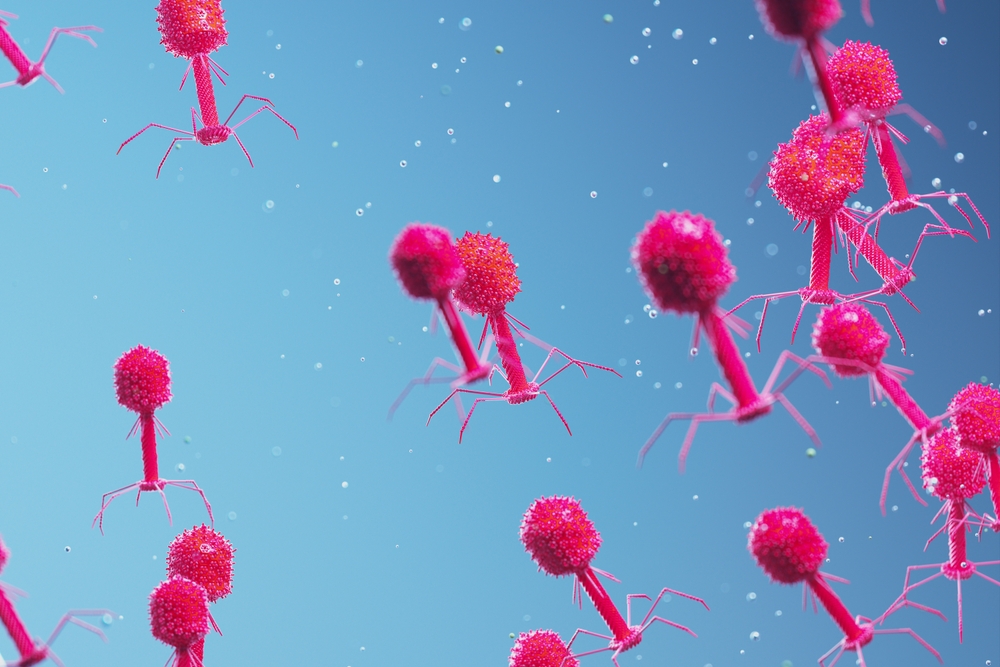

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect and kill bacteria. They are one of the most abundant creatures on the planet, and are often highly specific, each coordinated to attack only one bacterial species.

Structurally, they resemble microscopic syringes. Use a DNA-packed “head” section and a tail section packed with spiny fibers that latch into bacteria and inject genetic payloads.

Nevertheless, phages are still not safe from parasites. They can target small genetic elements called “phage satellites.”

As part of the study, the team focused on a powerful phage satellite called capsid-forming phage-induced chromosome islands (CF-PICI). These genetic elements are able to spread genes due to antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity, and are found in over 200 bacterial species.

However, it was unclear how they were able to move efficiently.

How CF-PICI attacks other bacterial species

First discovered by the team in 2023, CF-PICIS can build its own capsid (the “head” of the virus), but lacks a tail. In other words, by itself, it produces non-infectious particles and cannot infect bacteriophages.

In their latest research, researchers discovered a missing part of the puzzle: the CF-PICIS hijack tail has a tail from unrelated phages, creating a hybrid “chimeric” virus. The result is chimeric phages carrying CF-PICI DNA within their own capsids, but with a phage-derived tail.

Importantly, some CF-PICIs hijack tails of completely different phage species, effectively expanding the host range. Because the tail determines which bacteria are targeted, this copyright infringement causes CF-PICI to penetrate new bacterial species and explain essentially a widespread abundance.

Developing powerful new diagnostics for ABR

Researchers say that its meaning may be important to science. By understanding and utilizing this molecular copyright infringement, researchers believe that satellites can be redesigned to target antibiotic-resistant bacteria, overcome stubborn bacterial defenses such as biofilms, and even develop powerful new diagnostic tools.

“These pirate satellites don’t just tell us how bacteria share dangerous properties,” explained Dr. Tiago Diaz da Costa, an Imperial School of Life Sciences. “They were able to outmane some of the most challenging infectious diseases we are facing and stimulate the next generation of treatments and testing.”

Professor Jose Penades of the Imperial Bureau of Infectious Diseases added: “Our early studies first identified these strange genetic factors.

“We found that these mobile gene elements form capsids that can exchange ‘tails’ taken from other phages to put their own DNA into host cells. It’s an ingenious habit of evolutionary biology, but it also teaches you how to spread antibiotic-resistant genes through a process called transformation. ”

The Imperial Team hopes to file patents to further develop the work and begin testing the technology’s translation application.

AI Co-Scientist Tools Make New Advances

The linked projects were coordinated through the Fleming Initiative (partnership between Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust).

Called “co-scientists,” the platform is designed to help scientists develop smarter experiments and accelerate their discoveries.

To test the platform, the Imperial team raised the same basic scientific questions that pushed their work. How does CF-PICI spread across so many bacterial species?

Armed at this starting point, using web searches, research papers and databases, AI independently generated independently generated hypotheses reflecting the team’s own experimentally demonstrated ideas.

Researchers say this shows the extraordinary potential of AI systems for “super charging science” by accelerating it rather than replacing human insights.

Source link