Even if you don’t remember many facts from high school biology, you may still remember the cells, eggs and sperm needed to make a baby. Maybe you can imagine a swarm of sperm cells fighting each other in a race that would become the first person to penetrate the egg.

For decades, scientific literature has explained the concept of humanity in this way, with cells reflecting the perceived roles of women and men in society. The eggs were thought to be passive while the sperm was active.

Over time, scientists realized that sperm is too weak to penetrate the egg, and that the union is more mutual because the two cells work together. It is no coincidence that these findings were made in the same time when new cultural ideas for a more egalitarian gender role were established.

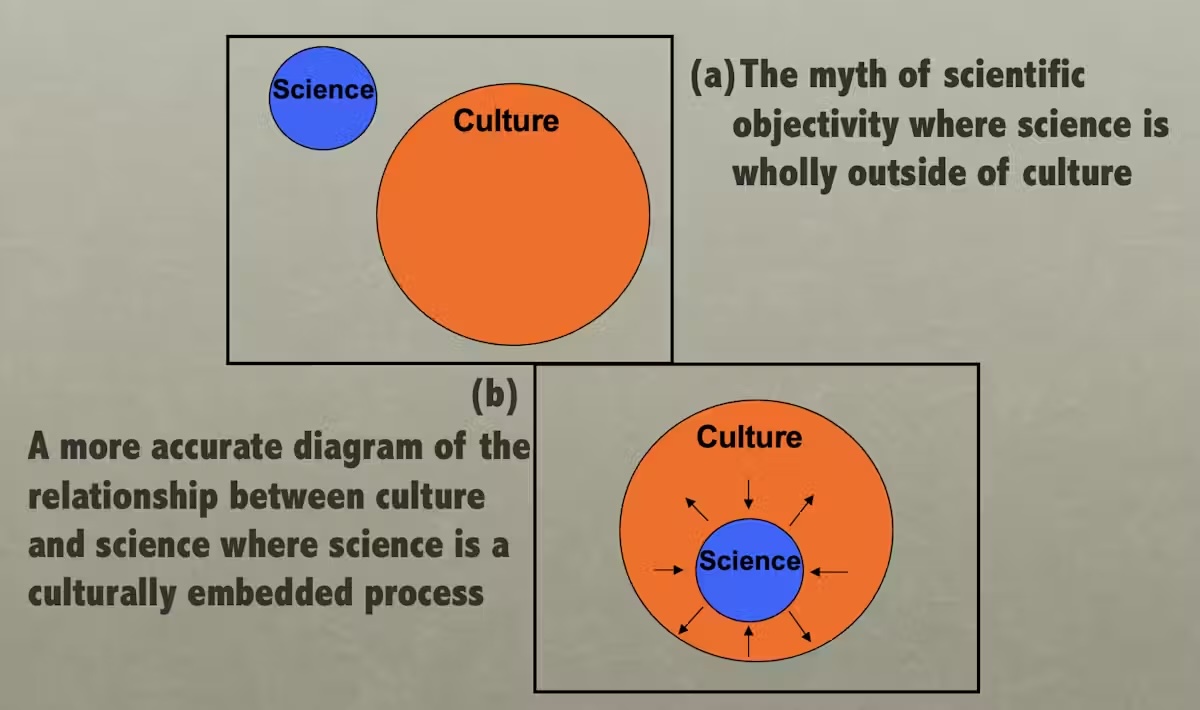

Scientist Ludwik Fleck is believed to have first described science as a cultural practice in the 1930s. Since then, understanding continues to build that scientific knowledge is consistent with the cultural norms of the time.

Despite these insights, beyond political differences, people continue to strive for the idea that they are rational and separable from scientific values and beliefs, and continue to demand scientific objectivity.

When I entered my PhD, I felt the same way about the 2001 Neuroscience Program. But after reading a book by biologist Anne Faust Sterling, a book called Sex the Body put me on a different path. It systematically exposed ideas of scientific objectivity and demonstrated how cultural ideas about gender, gender and sexuality could not be separated from scientific discoveries. By the time I completed my PhD, I began to integrate social, historical and political contexts and look at my research more comprehensively.

From questions that scientists have begun, the beliefs of those who are conducting the research, their choice of research design, interpretation of the final results, and cultural ideas always inform “science.” What if fair science is not possible?

You might like it

The emergence of ideas of scientific objectivity

Science has become synonymous with the objectivity of the Western University System over the past few hundred years.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, some Europeans gained traction in challenging religiously appointed royal order. The integration of the university system has led to trusting religious leaders who interpret the word “God” and trusting “humans,” to making rational decisions for themselves and trusting scientists who interpret “nature.” The University System has become an important site for legalizing claims through theory and research.

Previously, people would generate knowledge about their world, but there were no strict boundaries between what is now called the humanities, such as history, English, philosophy, biology, chemistry, physics and other sciences. Over time, people split the discipline into categories as questions arise about how to trust political decisions. Subjective and objective. The division came with the creation of the opposites of other binary, including closely related emotional/rationality disparities. These categories were not simply considered opposite, but they looked at objectivity and rationality in a good hierarchy.

A closer look shows that these binary systems are optionally self-enhanced.

Science is human effort

Science is a field of research conducted by humans. These people, called scientists, are just like everyone else, part of the cultural system. Our scientists are part of our family and have a political perspective. We watch the same movies and TV shows and listen to the same music as non-scientists. We read the same newspapers, cheer on the same sports teams, and enjoy the same hobbies as others.

All of these clearly “cultural” parts of our lives are trying to influence how scientists approach our work and what we consider to be “common sense” that we don’t question when we experiment.

Beyond the individual scientists, the type of research carried out is based on questions considered relevant by dominant social norms.

For example, when I work in neuroscience in my PhD, I saw that different assumptions about hierarchy can affect a particular experiment or even an entire field. Neuroscience focuses on what is called the central nervous system. The name itself describes a hierarchical model, with parts of the body “in charge” of the rest. Even within the central nervous system there was a conceptual hierarchy in which the brain controls the spinal cord.

My research saw more of what happened peripherally in the muscles, but the dominant model had the brain at the top. The perceived idea that the system needs a boss reflects cultural assumptions. However, I realized that I can analyze the system differently and ask a variety of questions. Instead of having the brain at the top, another model can focus on how the whole system works together and works together.

Every experiment has a burned assumption that is also taken for granted, including definitions. Scientific experiments can be self-fulfilling prophecies.

For example, billions of dollars are spent trying to portray gender differences. However, the definitions of men and women are rarely stated in these research papers. At the same time, evidence is mounted that these binary categories are modern inventions that are not based on clear physical differences.

Related: Is there really a difference between men and women’s brains? Emerging Science is revealing the answer.

However, as categories have been tested many times, some differences are ultimately discovered without compiling these results into a statistical model. In many cases, no so-called negative findings that do not identify any significant differences have been reported. Sometimes, meta-analyses based on multiple studies that investigated the same question reveal these statistical errors, like searching for sex-related brain differences. Similar patterns of slippery definitions occur that reinforce the assumptions adopted in categories of race, sexuality and other socially created differences.

Finally, the final results of the experiment can be interpreted in a variety of ways, adding another point where cultural values are injected into the final scientific conclusion.

Settle into science when there is no objectivity

vaccine. abortion. Climate change. Sex category. Science is at the heart of most of today’s hottest political debates. There are many differences, but the desire to separate politics and science seems to be shared. On both sides of the political disparity there is accusation that scientists on the other side cannot be trusted because of political bias.

Consider the recent controversy over the US Disease Control Vaccine Advisory Panel. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired all members of the Advisory Committee on Vaccination Practices and said they were biased, but some democratic lawmakers argued that his move would introduce people who are biased towards pushing his vaccine’s ceptical agenda.

How do people produce reliable knowledge when it is impossible to remove all biases?

The understanding that all knowledge is created through a cultural process allows two or more different truths to coexist. This reality centers around many of today’s most controversial subjects. But this does not mean you have to believe in all truths equally – it is called perfect cultural relativism. This perspective ignores the need for people to come to make decisions together about truth and reality.

Instead, key scholars provide democratic processes for people to decide which values are important and for what purposes they should develop their knowledge. For example, some of my work focuses on expanding the model for Dutch science shops in the 1970s. Community groups come to the university setting and arrive to share concerns and needs for determining the research agenda. Other researchers have documented other joint practices between scientists and marginalized communities and policy changes.

A more accurate view of science argues that pure objectivity is impossible. However, leaving behind the myth of objectivity, it will not be simple in the future. Instead of a belief in science that knows everything, we face the reality that humans are responsible for what is being studied, how it is being studied, and what conclusions are drawn from such research.

This knowledge gives us the opportunity to deliberately set social values informing scientific research. This requires decisions on how people agree on these values. These contracts are not always universal and may instead depend on the context of who and what a particular study affects. Although not simple, these insights have been used to study science both internally and internationally for decades, but it could force more honest conversations between political positions.

This edited article will be republished from the conversation under a Creative Commons license. Please read the original article.

Source link