Although global temperatures are warmer, the Northern Hemisphere winters are still marked by cold snaps and extreme snowfall events. Sometimes it caused more than $1 billion in damages, including the deep 2021 freeze in Texas and Oklahoma.

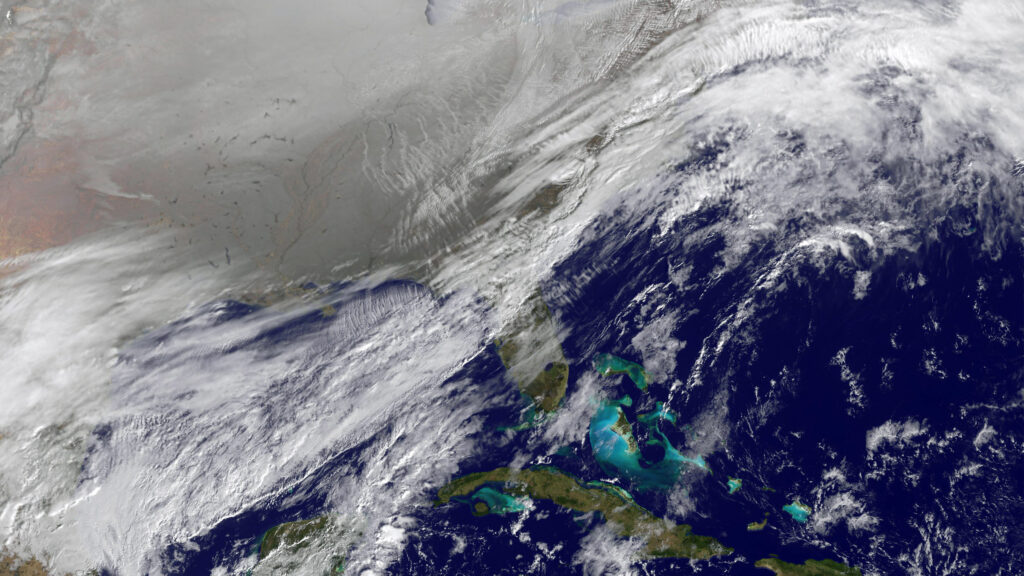

Now, new research suggests that these extreme extremes are due to an increasingly common pattern of polar zones, low-pressure zones that normally circulate in the Arctic. This vortex disruption causes it to deform and stretch, expelling cold air into Canada and the United States. These confusions are becoming more common as the Arctic warms up.

“Absolutely, extreme cold and severe winter weather, heavy snow, and deep snow are associated with these growing events,” Judas Cohen, director of seasonal forecasts for air and environmental studies and visiting scientist at MIT, told Live Science.

You might like it

Cohen and his team looked into how these events evolve in the stratosphere. This is the middle layer of the atmosphere, beginning at about 12 miles (19 kilometers). Understanding how these patterns change could help meteorologists make predictions for longer ranges, said Madison, atmospheric scientist at the University of Wisconsin, who was not involved in the study.

“Knowing this information is useful for many energy applications [and] Lang spoke to Live Science. Will the pipe burst? Will insurance claims rise sharply this winter? ”

Polar water usually circulates around the Arctic, like a rotating top. Sometimes it collapses dramatically, leading to polar airs that usually run through Northern Europe and Asia. These collapses can, but not always, cause cold snaps in North America.

“There was this big question mark about what will happen in North America,” Lang said.

Related: We are suffering from record-breaking cold: What’s going on with the polar vortex?

Cohen and his colleagues looked at stratospheric data from satellite observations from 1980 to 2021, as well as winter weather records from the same era. They discovered that apart from complete collapse, polar water often wobbles and grows. There are five different common patterns in the stratosphere, and researchers reported in the journal Science Advances on July 11, with two in particular related to the cold climate of soaking in Canada and the US during these stretching events.

Stretch events are generally increasing, Cohen said, but there have also been changes in the type of stretch.

One stratospheric pattern tends to bring cold air to the East Coast, while the other creates coldness in the Midwest and plains. Since 2015, researchers have discovered that Western patterns are more common. The reason is not entirely clear, but this change appears to be related to La Niña, an unusually cold temperature pattern in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Over the past few decades, there have been multiple multi-year La Niña events.

Researchers were able to detect some regularities in a way that shifts the polar vortices between the five patterns. “In that short range, it has the poorest accuracy,” he said. “This paper could be useful in that time frame.”

One big question is how these polar water trends change over time as the earth warms, Lang said.

Cohen and his team have also seen the question. The polar vortex is controlled by waves in the air, he said, and the most influential standing waves now surpass Eurasia, with warm ridges to the west and cool troughs to the east, driven by patterns of warming in the Arctic Circle.

Now, melted sea ice increases the temperature difference between the west and east, strengthening waves that can destroy vortices, Cohen said. If sea ice disappears, the pattern can collapse and turn over. Despite the overall global warming, instead of the surprising cold winter events, winters may suddenly become much dry.

“We could be like the Southern Hemisphere, where we rarely get polar vortex failures,” Cohen said.

Source link