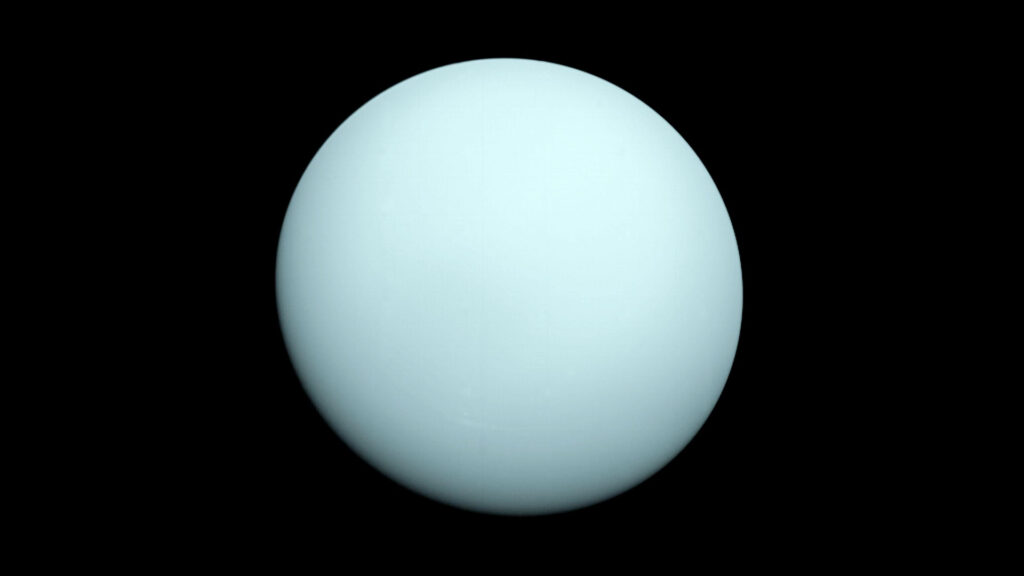

Scientists have discovered that Uranus emits even more internal heat than it receives from sunlight. This discovery contradicts the observation of a distant gas giant created by NASA’s Voyager 2 probe nearly 40 years ago.

Scientists led by XINYUE YANG at the University of Houston analyzed decades of measurements from spacecraft and computer models and found that Uranus emits 12.5% more inward heat than the amount of heat received from the Sun. However, its amount is much less than the internal heat of other outer solar system planets, such as Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune. They emit 100% more heat than you get from the sun.

Researchers behind this new study say that Uranus’ internal heat helps to uncover the origins of a world where curiosity is leaning hard. “This means we are slowly losing the rest of the heat from early history. This is an important part of the puzzle that will help us understand its origins and how it has changed over time,” he said in his voice.

You might like it

In 1986, the iconic Voyager 2 probe was flew by Uranus, leaving the solar system and heading into interstellar space. Much of what scientists understand about the seventh planet from the Sun comes from its flyby.

However, we find that we may have caught Uranus at a strange time, and some of the measured figures 2 collected may have been distorted by a surge in the solar weather that occurred during the Earth’s flyby.

By reviewing a large set of archival data and combining it with computer models, researchers now believe that the internal heat released by Uranus could imply a completely different internal structure or evolutionary history of the planet we thought we knew. Uranus is believed to have formed about 4.5 billion years ago along with the rest of the solar system, and NASA believes it formed near the sun before moving to the outer solar system about 5 billion years later. But the story is now being questioned by these new discoveries.

“From a scientific perspective, this study will help you better understand Uranus and other giant planets,” Wang said in a statement. Researchers also believe this new understanding of Uranus’ internal processes will help NASA and other agencies plan missions to distant planets.

In 2022, the National Academy of Sciences flagged the concept of missions concept known as Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP) as one of the highest priority planetary science missions of the next decade. But even so, before massive budget uncertainty clashed with NASA and the scientific community, scientists knew it would be difficult to move such an ambitious and expensive mission, in the wake of President Donald Trump’s overhaul of US government spending.

“There are many hurdles to come – political, financial, technical – we are not falling into fantasies,” Lee Fletcher, a planetary scientist at the University of Leicester in the UK, told Space.com in 2022 when the report was released. “We have about 10 years to move from paper missions to hardware at launch fairing. We don’t have time to lose.”

Whether new research on Uranus will help boost support for such a mission, scientists have already called these new results themselves groundbreaking. Research co-author Liming Li said that research into Uranus’ internal heat not only helps us to better understand the distant, ice world, but also informs us of research into similar processes on Earth, including our own changing climate.

“Understanding how Uranus stores heat and makes it hot gives us valuable insight into the fundamental processes that shape the planet’s atmosphere, weather systems and climate systems,” Lee said in a statement. “These discoveries will help broaden our perspective on the Earth’s atmospheric systems and the challenges of climate change.”

Research into Uranus’ internal heat was published in the Journal Geophysical Research Book.

This article was originally published on Space.com.

Source link