As chipmakers race to meet the surge in demand for generative AI and next-generation electronics, a less obvious problem: PFAS waste is gaining urgency.

A new review analyzes how the semiconductor industry deals with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), permanent chemicals that are deeply embedded in modern manufacturing.

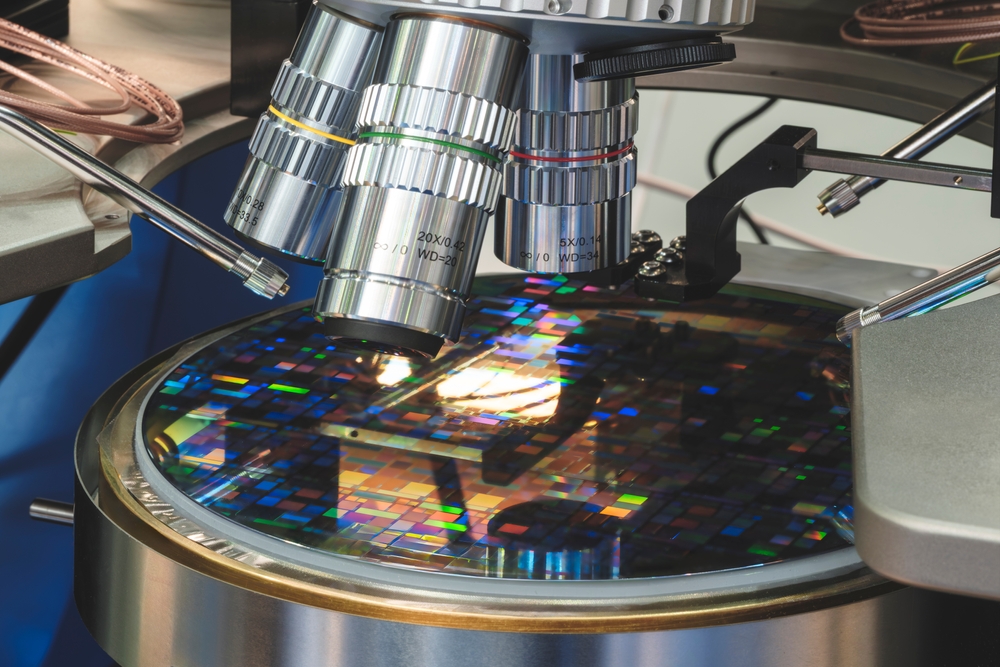

PFAS are highly valued in chip manufacturing because of their ability to withstand extreme heat and harsh chemical conditions. These are essential to processes such as photolithography and etching that allow engineers to engrave microscopic circuits onto silicon wafers.

However, the chemical stability of PFAS waste makes it incredibly useful on factory floors, making it incredibly persistent in the environment.

Complex industrial flow

Managing PFAS waste from semiconductor manufacturing facilities is no easy feat. A single large manufacturing plant can generate thousands of cubic meters of wastewater every day.

Wastewater is not contaminated with just one compound. They typically contain complex mixtures of PFAS, solvents, metals, and salts, all of which interact in ways that are difficult to predict.

The review grew out of a 2024 workshop funded by the National Science Foundation that brought together researchers, industry representatives, and government officials to plan practical solutions.

The resulting paper integrates insights from that conference and findings from more than 160 scientific studies.

Researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Arizona State University, Oregon State University and others contributed to the effort. Together, they aimed to provide a clear assessment of the state of the science and what needs to happen next.

Three priorities for tackling PFAS waste

This review identifies three core priorities for addressing PFAS waste in semiconductor manufacturing: better monitoring, more effective separation, and reliable destruction.

First of all, monitoring. Many of the PFAS compounds used in chip manufacturing are proprietary and difficult for outside researchers to track.

Artificial intelligence, combined with advanced analytical tools such as high-resolution mass spectrometry, could help identify specific compounds and track how they change during manufacturing. Without accurate detection, it is nearly impossible to design effective treatment systems.

Second, living apart. Destroying PFAS often requires concentrating them and separating them from other wastewater components. Technologies under consideration include new absorption materials, advanced membranes, and electrochemical methods.

Although some of these approaches were originally developed for municipal water treatment, semiconducting PFAS wastes are much more chemically complex and require significant adaptation.

Third, destruction. Breaking the strong carbon-fluorine bonds that define PFAS is notoriously difficult. Promising options include plasma-based systems and electrochemical oxidation. Both aim to break down molecules rather than transfer them from water to another medium.

The challenge lies in scaling these technologies to handle industrial volumes without disrupting tightly optimized production lines.

Non-disruptive integration

Semiconductor manufacturing facilities are among the most complex industrial environments in the world. A single plant can contain hundreds or even thousands of tightly coordinated steps.

New PFAS waste treatment technologies must fit into this complex ecosystem without compromising yield, safety, or efficiency.

This integration challenge is further exacerbated by regulatory uncertainty. As governments around the world seek to tighten regulations regarding PFAS, manufacturers must anticipate future standards while continuing to expand production capacity.

At the same time, researchers often struggle to access actual industrial waste streams for testing, which slows progress from lab-scale experiments to full-scale deployment.

Collaboration window

Despite the hurdles, experts see a unique opportunity. The semiconductor sector is growing rapidly and attracting significant investment from both private industry and government.

This economic momentum could accelerate the development of practical PFAS waste solutions, especially through greater collaboration between academia, industry, and policy communities.

The long-term goal is ambitious: to develop compact, cost-effective systems that can treat or remove PFAS waste on-site, moving the industry closer to zero emissions.

Achieving that vision will require not only technological breakthroughs, but also transparency, shared data, and a coordinated policy framework.

As the world becomes increasingly reliant on advanced chips, the question is no longer whether PFAS waste requires attention.

Ensuring that the digital future does not come with hidden chemical costs will depend on how quickly the industry can align innovation and environmental responsibility.

Source link