Microbes in the gut can help the immune system fight cancer, and a fiber-rich diet may be key to reaping the benefits, a study in mice suggests.

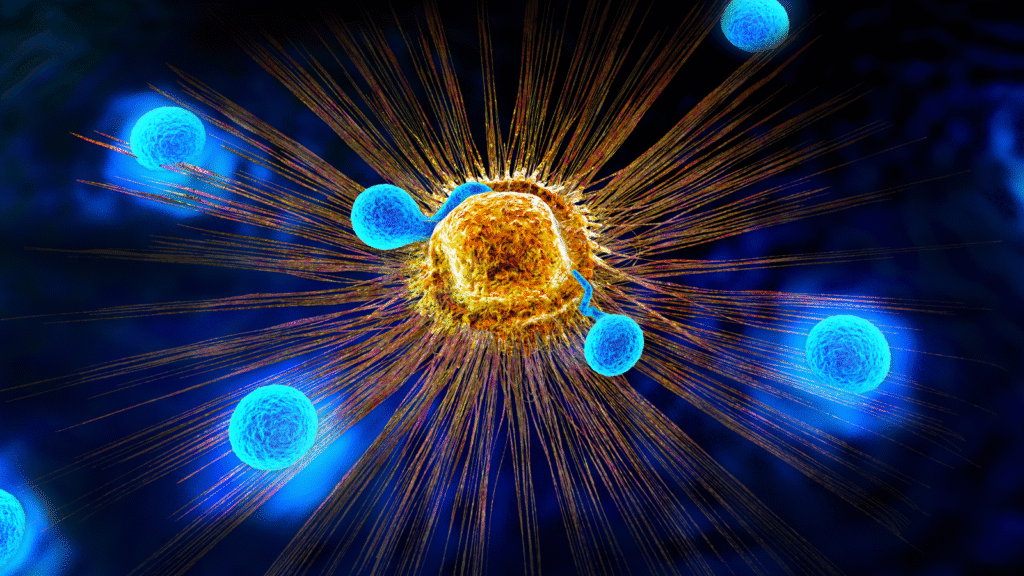

The immune system plays an important role in the body’s fight against cancer. At the forefront of this resistance are CD8+ killer T cells, a type of immune cell that surrounds tumors and kills cancer cells. However, as each battle continues, these cells become exhausted and are no longer able to find tumors effectively. So there is a need for treatments that give cells enough oomph to finish their job.

Now, in a study published Nov. 11 in the journal Immunity, researchers report that simple dietary changes can influence the gut microbiome (the collection of microbial species in the gastrointestinal tract) and help revive these important immune cells.

you may like

The team, led by Dr. Sammy Bedoui, an immunologist at the University of Melbourne in Australia, did not set out to study cancer. Instead, they told Live Science that their project began nearly a decade ago as a “bolt-in-the-blue discovery study” with no specific outcome in mind.

The research team was extensively investigating how CD8+ T cells protect the body. Part of their work involved mice genetically engineered to lack a gut microbiome, and the researchers noticed that T cells transferred to these rodents began to die after a few weeks. They began looking for factors released by the microbiome that could help T cells proliferate.

In a 2019 paper, they discovered that factor. When large amounts of dietary fiber reach the intestines, it is fermented by bacteria in the colon. This process releases various chemicals, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Bedui, along with study co-author and senior research scientist Annabelle Bakchem, showed that a particular SCFA (butyrate) rejuvenates exhausted T cells.

“They are very similar to the cells we want when treating patients and mice with immunotherapy,” Bedoui said.

The researchers, who first showed this effect in healthy mice with no microbiome, built on this idea in a new study. They tested whether butyrate could increase T cells in mice with skin cancer melanoma. The researchers fed half of these mice a high-fiber diet, which increased SCFA production by gut microbes. The mice remained tumor-free longer and had smaller tumors overall than mice on a low-fiber diet. In other words, cancer progressed more slowly in the fiber-rich group.

In another experiment, the team bred mice lacking T cells and applied the same protocol. In these mice, a high-fiber diet did not improve cancer outcomes, suggesting that something specific to the effects of fiber on T cells slows disease progression.

The research team investigated how SCFAs alter T cells in mice. The researchers found more T cells specialized to fight melanoma in mice fed more fiber. Specifically, these cells were found in tumor-draining lymph nodes, which are staging posts where T cells gather before tackling tumors.

you may like

Importantly, these cells had proteins that showed their ability to fight cancer. “They can remain in the body for a very long time,” Bachem said of the cells. “They can be successfully activated and then differentiated into different subsets.”

Bedoui said the team’s findings were different from previous studies in that they did not focus on the medical value of specific bacterial species. Not the only bug in the team’s analysis contributed to the impact. It was a group effort.

“In terms of bacteria, it’s less about who’s there and more about what the bacteria are doing,” Bedoui says.

These discoveries have opened a rich vein of future research. Bedui and Bakchem will now investigate in clinical studies whether adding dietary fiber may help human melanoma patients, and whether butyrate may restore mojo to other T cells.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not provide medical or dietary advice.

Source link