The fossilized skeletons of Jurassic reptiles, which look like some lizards, were excavated on the Isle of Skye in Scotland.

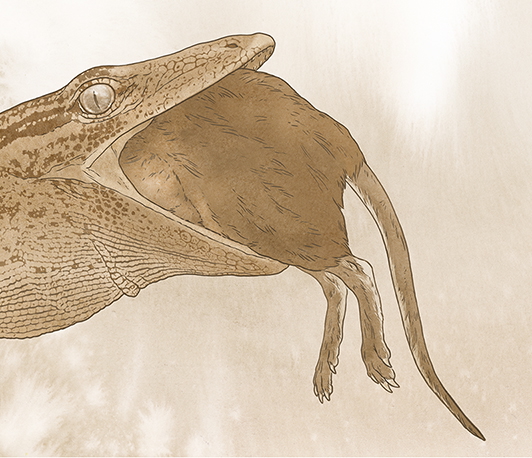

The mystical lizard had hooked its snake-like teeth to hunt its prey 167 million years ago, a new study found.

You might like it

The B. elgolensis was about 16 inches (41 cm) long, but according to a statement released by researchers, it is still one of the largest lizards in the ecosystem. Scientists suspect they hunted small lizards, early mammals, and even young dinosaurs, including small herbivorous heterodontosaurus and predatory bird-like Parabians.

It had snake-like jaws and curved teeth similar to modern pythons, but its body was short, with fully formed lizard-like limbs. B. elgolensis also had gecko-like features in some of the bones, including the dorsal surface of the skull. Researchers still decipher the evolutionary history of B. elgolensis, but their discoveries could change the way snakes see their evolutionary evolution.

Related: Night Lizard Survives the Asteroid Strike, Killing Dinosaurs.

Scientists now have a scattered understanding of early lizards and snake evolution. Both animals belong to a group called Squamata, which appeared about 109 million years ago. There are some overlap between the members of the group, but the lizard comes first, and generally has four limbs, while the snake is the limbs.

“The Jurassic fossil deposits of the Isle of Skye are of global importance to understand the early evolution of many living groups, including lizards, which were beginning to diversify around this time,” said Susan Evans, professor of vertebrate morphology and paleontology at University College London.

Study co-author Stig Walsh, a senior curator of vertebrate paleontology at the National Museum of Scotland, first discovered the fossil of B. Elgolensis in 2015. The team then spent time preparing and studying the specimens.

The researcher is B. Elgolensis has determined that it belongs to the Squamata subgroup called Parviraptoridae, previously known only from other fossil fragments. The snake-like bones were found close to the gecko-like bone, but some scientists assumed they came from two separate animals. The new fossil confirms that one species actually has both functions, according to the statement.

“I first described Parviraptorids 30 years ago, based on more fragmentary materials, so it’s like finding the top of a Jigsaw box years after baffling the original photo from a handful of pieces,” Evans said. “As shown in this new specimen, the mosaic of primitive and special features found in Parviraptorids is an important reminder that evolutionary pathways may be unpredictable.”

Researchers still don’t know if the snake evolved from a species like B. elgolensis, or if the snake independently evolved similar mouth parts. B. elgolensis is a stem lineage within Squamata and can also help produce all lizards and snakes.

“These fossils take us quite a bit far, but that’s not all of our ways,” said Rogerbenson, Macaula curator at the Museum of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, in a statement. “But that excites us even more about the possibility of understanding where the snakes came from.”

Source link