Since 2002, the continent has lost so much water, surpassing the ice sheet as the biggest contributor to sea level rise in the world, new research reveals.

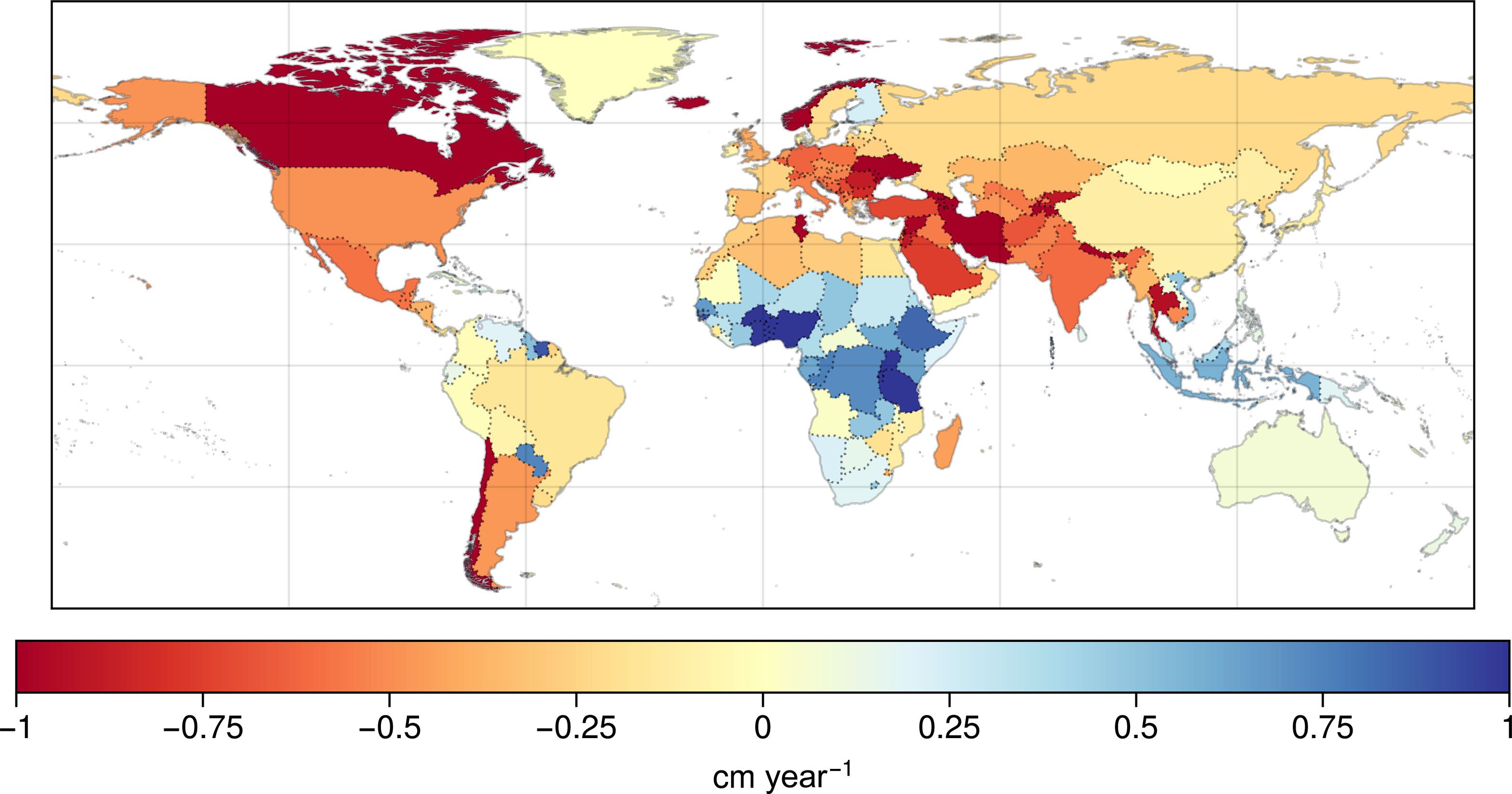

Nearly 70% of this loss comes from unidentified groundwater extraction that removes water from the deep aquifer and eventually moves it into the sea. Scientists said that “hotspots” are rapidly aerated to merge into four “mega-dry” regions, along with the rate of increase in evaporation due to climate change.

“There are very few places that aren’t dry,” Jay Famiglietti, a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability, told Live Science. “I’ve been watching it for 20 years and it got worse, worse, worse.”

You might like it

To measure continental aridity, researchers used data from satellites that respond to small mass changes on Earth. Gravity pulls down the satellite when the area increases the weight of the water, and releases it back into its original orbit when the water is lost. The ground resolution is about 15 miles (25 kilometers), which is sufficient to detect small changes in the scale of the region, Famiglietti said.

Dry hotspots are areas with large aquifers that humans have exploited in large quantities for decades, which means they have a high percentage of water loss, Famiglietti said. These hotspots include the North China Plain, Northwest India and Central Valley in California, where human activity and evaporation have lost enormous amounts of water. This water enters the river that leads to the ocean, or into a river that is raining from the ocean atmosphere, and eventually rises to sea level.

New findings published July 25th in Journal Science Advances show that adria hotspots are expanding rapidly, and many of these regions are combined. “South Asia is a great example,” Famiglietti said. “There used to be four or five hot spots around the Himalayas. Now it’s been around for a long time.”

Related: “Existential Threats Affecting Billions”: Three-quarters of Earth’s Land have been permanently dried over the past 30 years

The authors of this study were called mega-arid regions, which are regions of the size of these continents. They identified three such regions around the world. All of these are in the Northern Hemisphere. One spans Alaska, northern Canada, northern Russia, and the other spans Western Europe, with the third largest spanning Southwest North America and Central America. The dry area is growing very quickly. “It’s like creeping mold and viruses spreading throughout the landscape,” Famiglietti said.

It is unclear why there are no huge arid areas in the Southern Hemisphere, but researchers believe it somehow links it to a record-breaking El Niño event over a decade ago. “There are these kinds of changes in the drying rate and extreme expansion that took place around 2014,” Famiglietti said.

According to Famiglietti, the dryness of the hotspot appeared to jump primarily into the Northern Hemisphere, mainly from being in the Southern Hemisphere during the global transition from the extremely powerful La Niña to the most powerful El Niño in record time between 2011 and 2014. His team said he was still trying to understand why.

“The most important natural resources”

Drying in Alaska, Canada and Russia is driven primarily by permafrost and ice melting, while drying in Western Europe is caused by drought, Familyetti said. The southwest of the United States was dry before humans pumped groundwater, which now spread across Mexico and Central America.

Around the world, only the tropical is wet, which is also driven by global warming. Decomposing this trend, researchers have found that 101 countries, in which 75% of the world’s population lives, have lost freshwater in the past 22 years.

“Groundwater is becoming the most important natural resource in these arid parts of the world,” Famiglietti said.

Continental aridity affects food production, biodiversity, natural catastrophes, sea level and lifestyle, so its meaning is profound. As we continue to cook the planet, we need more groundwater to irrigate our crops and maintain our population, digging people deeper into the aquifer.

“It’s a very broad range,” Hrishikesh Chandanpurkar, the lead author of Hrishikesh Chandanpurkar, Earth Systems Scientist at Arizona State University, told Live Science via email. “Current water management efforts need to be revisited on the scaffolding of war.”

Groundwater depletion cannot be reversed, but changes in water use, such as ending flood irrigation, could go a long way, Famiglietti said. He said that it would also help us to mitigate climate change.

“We’re already seeing what will happen if we don’t change,” Familytti said. For example, wildfires have increased severity and frequency, which is a direct result of water loss and warmth in temperature, he said. Many regions have also experienced water stress, with sea levels rising by 3.5 inches (9 cm) over the past 25 years.

“We don’t have to stop everything,” Famiglietti said. “You need to do things as efficiently as possible.”

Source link