Paleoanthropologists have unveiled the world’s most complete skeleton of Homo habilis, an ancestor of humans who lived in northern Kenya more than 2 million years ago. Collection of fossil bones revealed unusually strong arms that distinguish H. habilis from later species.

The bones were first discovered in 2012 by a team of researchers led by Meave Leakey of the Turkana Basin Research Institute, and subsequently presented at a research conference in 2015. Now, the full analysis of the remains is described in a paper published in the journal ‘The Anatomical Record’ on Tuesday (January 13).

you may like

“There are only three other highly fragmentary and incomplete partial skeletons known of this important species,” study lead author Fred Grein, a paleoanthropologist at Stony Brook University in New York, said in a statement. The discovery is important because it represents both the most complete and oldest partial skeleton of early humans, the researchers said in their study.

Homo habilis was a transitional species in that it was the first named species that marked the beginning of our genus after evolving from Australopithecus, the lineage that includes the famous fossil skeleton Lucy, but it differed from our better-understood ancestor Homo erectus, which spread throughout the world. Homo habilis fossils are therefore key to understanding the adaptations of our early ancestors. Hominidae includes modern humans and extinct relatives.

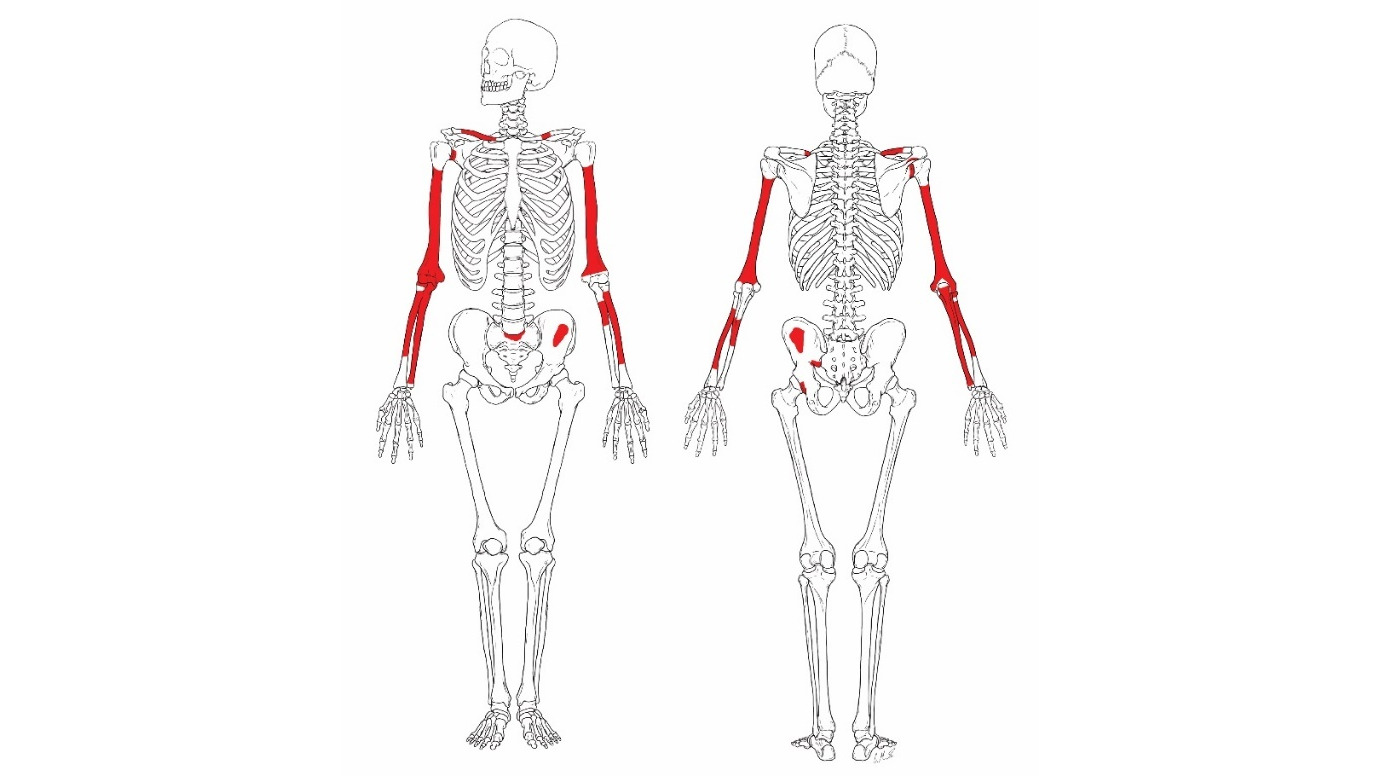

KNM-ER 64061 Close analysis of the fossil reveals that the arm bones of Homo habilis are similar to those of other early hominin specimens and some australopithecines. For example, Homo habilis had longer forearms than later Homo erectus, and heavy, thick arm bones similar to Australopithecus.

Based on the length of the humerus (upper arm bone), researchers determined that KNM-ER 64061 was a young adult approximately 5 feet 3 inches (160 centimeters) tall. From leg bone fragments, they estimated that the individual weighed only about 67.7 pounds (30.7 kilograms). These anatomical features suggest that H. habilis retains similar upper limb proportions to Australopithecus and is shorter and lighter than H. erectus.

However, the researchers say these characteristics do not necessarily mean that H. habilis can fly through trees. “The relatively long forearms of H. habilis may have allowed this species a higher degree of arboreal locomotion than H. erectus, but whether H. habilis was actually arboreal remains open to speculation,” the researchers wrote in their study.

“The limbs of Homo habilis are attracting increasing attention,” study co-author Ashley Hammond, a paleoanthropologist at the Catalan Institute of Paleontology Mikel Courzafont, said in a statement. “The limbs of Homo habilis are attracting increasing attention,” and the new skeleton “confirms that the arms were quite long and strong. What remains elusive is the size and proportions of the lower limbs.”

Although only a few pelvic fragments of KNM-ER 64061 were recovered, they suggest that this H. habilis individual may have had a gait more similar to H. erectus than to early Australopithecus, the researchers noted in the study.

“Future fossils of the lower limbs of Homo habilis are needed, which could further change our view of this major species,” Hammond said in a statement.

The discovery of a surprisingly complete Homo habilis skeleton may also help paleoanthropologists classify the massive group of hominins that lived in eastern Africa between 2.2 million and 1.8 million years ago.

The researchers found that up to four species of hominin (Paranthropus boisei, Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and possibly Homo erectus) lived in the same place at about the same time. Additionally, because H. erectus appeared about 500,000 years before H. habilis disappeared from the fossil record, it is currently unknown whether H. habilis is an ancestor of H. erectus or a close relative.

Source link