The world’s oldest known sewn garments may have been pieces of animal skin sewn together with animal and plant string by indigenous peoples and left in an Oregon cave some 12,000 years ago, a new study has found.

Although its exact purpose is unknown, the sewn skin is “very likely a fragment of clothing or footwear,” potentially making it the only known piece of clothing to date recovered from the Pleistocene, the researchers said in a paper published February 4 in the journal Science Advances.

Amateur archaeologists discovered the stitched skin in 1958, but this study is the first time the artifacts have been dated. In their paper, the researchers determined that 55 animal and plant artifacts previously unearthed in two caves in Oregon, including sewn hides, cords and twine, date back to the Younger Dryas, a period of rapid cooling that occurred about 12,900 to 11,700 years ago.

you may like

The discovery provides clear evidence that North American indigenous peoples used complex techniques made from perishable materials to protect themselves from the worst of the cold. Sewing the leather sections together allowed for a close-fitting garment, which would have provided more warmth than a simple, loosely draped leather garment.

“We already knew they did it, but we just guessed and guessed what they were like,” Richard Rosencrance, a postdoctoral fellow in anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno and lead author of the study, told Live Science in an email. “They were skilled and serious seamstresses during the Ice Age.”

Clothing, along with other technologies needed to keep people warm, was essential for permanent settlement in northern latitudes, including the North American region. However, it is unclear exactly when humans first started wearing clothing, and the perishable nature of the materials makes it rare.

To date, there are only four sites in the Western Hemisphere where late Pleistocene non-skeletal animal and plant technology has been discovered, located in Oregon and Nevada. (The Late Pleistocene spans from 126,000 to 11,700 years ago and includes the last Ice Age.)

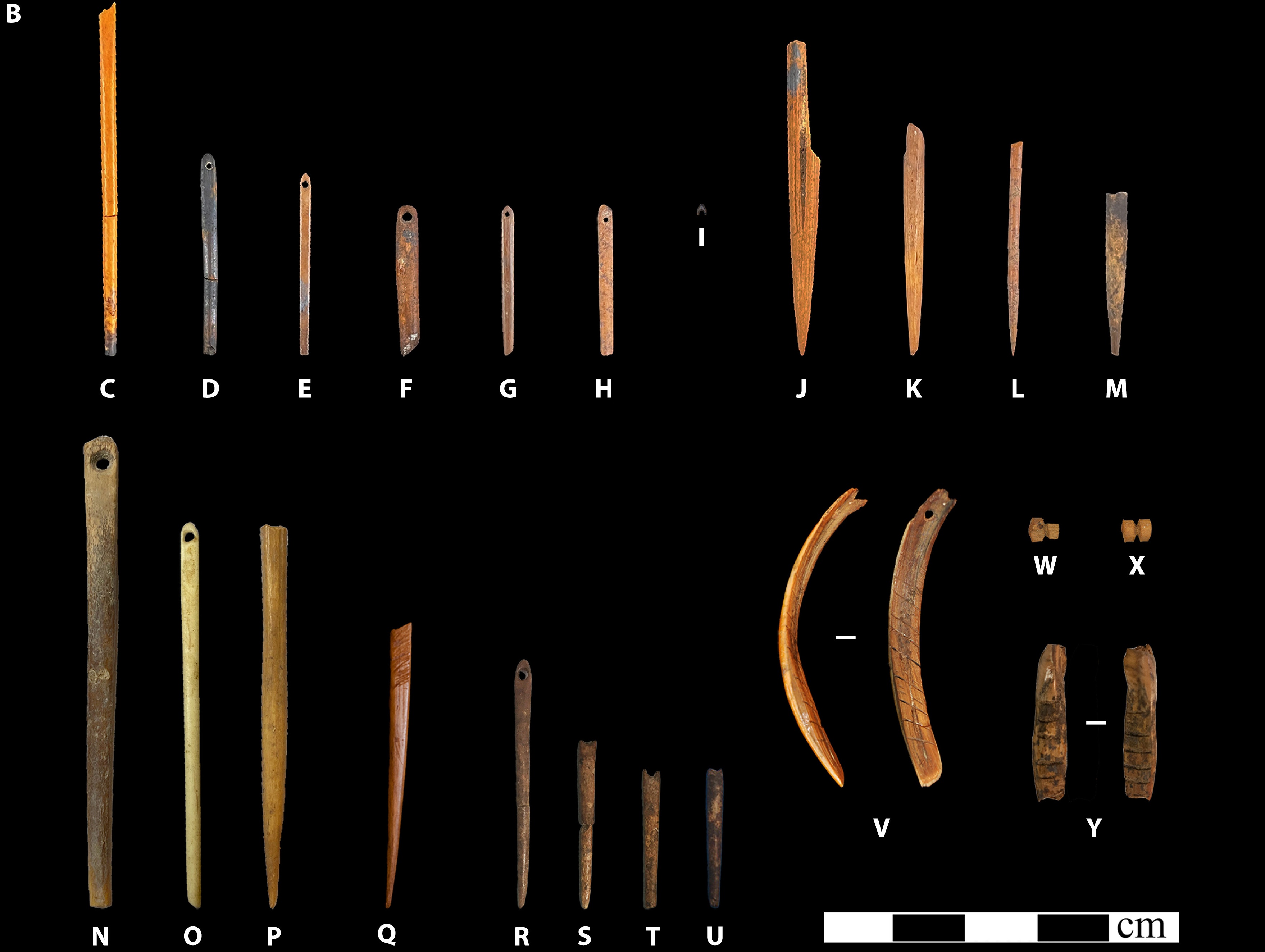

Archaeologists previously discovered the world’s largest collection of Late Pleistocene perishable tools at Cougar Mountain Cave and Paisley Cave in Oregon, according to a new study. These artifacts included 37 textile cords, baskets, and knots. 15 wooden utensils. Then I sewed the three pieces of skin together.

Rosenkrans and his team used radiocarbon dating to determine the age of these artifacts, confirming that they all date to the Younger Dryas period. The cord was woven using three strands and made using Sagebrush, Dogbane, Juniper, and Bitterbrush fibers. The cords were 0.13 to 1 inch (0.33 to 2.5 centimeters) wide, so they were likely used for a variety of purposes, the researchers said in the study.

Three pieces of animal skin were treated to remove hair, and strings made of a combination of plant fibers and animal hair were sewn onto the sides. The stitched hides are between 12,600 and 11,880 years old, and analysis of the chemical composition of the animal hides revealed they belonged to a North American moose (Cervus canadensis). (The world’s oldest known shoes were also unearthed in a cave in Oregon and date back about 10,400 years.)

The authors of the new study also examined 14 eyed bone needles and 3 eyeless bone needles previously discovered at Cougar Mountain and Paisley Cave, as well as nearby Conley Cave and Tule Lake Rockshelter. In addition, they examined four possible ornaments excavated at Connelly Cave, including a porcupine tooth with a hole in the top and lines carved into the surface.

“The presence of abundant bone needles, ornaments and very fine needles suggests that clothing was more than a practical survival strategy, it was also a means of expression and identity,” the authors write. “This evidence goes beyond previous assumptions and confirms that Pleistocene peoples in the Americas used clothing as both a survival technique and a social practice.”

Bone needles with eyes have been missing from Oregon’s archaeological record since about 11,700 years ago, suggesting that tight-fitting clothing became less important as the climate warmed, Rosencrance said.

Rosencrance, R.L., Smith, GM, McDonough, K.N., Jazwa, CS., Antonosian, M., Kallenbach, E.A., Connolly, T.J., Culleton, B.J., Pussmann, K., McGuinness, M., Jenkins, D.L., Stuber, D.O., Enzweig, P.E., and Roberts, P. (2026). The complex perishable technologies of the North American Great Basin reveal special late Pleistocene adaptations. Advances in Science, 12(6), eaec2916. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aec2916

Source link