Satellite images reveal that dozens of dams across the country, including the largest in Texas, may be at risk of collapse due to shifting ground beneath them. Inspections typically do not take these movements into account, suggesting that many of the country’s dams are in worse shape than previously realized.

This new discovery raises the prospect that thousands of dams that we do not monitor closely due to high costs and lack of personnel may be damaged and at risk of failure. But how big is the problem, and is it worth using satellite data to provide early warning?

you may like

changing ground

In a December 2025 presentation to the American Geophysical Union, scientists used 10 years of radar imagery from the Sentinel 1 satellite to identify dams that have moved due to land subsidence or uplift. Depending on the dam material, this can lead to the formation of cracks, especially if different parts of the structure are moving in opposite directions or at different speeds.

“This technology can help identify potential problems and alert the authorities,” lead researcher Mohammad Khorami, a geotechnical engineering postdoctoral fellow at Virginia Tech and the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, told Live Science.

The results are based on 41 high-risk hydroelectric dams that are greater than 50 feet (15 meters) in height and have a National Dam Inventory classification of “poor” or “unsatisfactory” condition. These are dams that have known deficiencies that compromise operational safety and require repair.

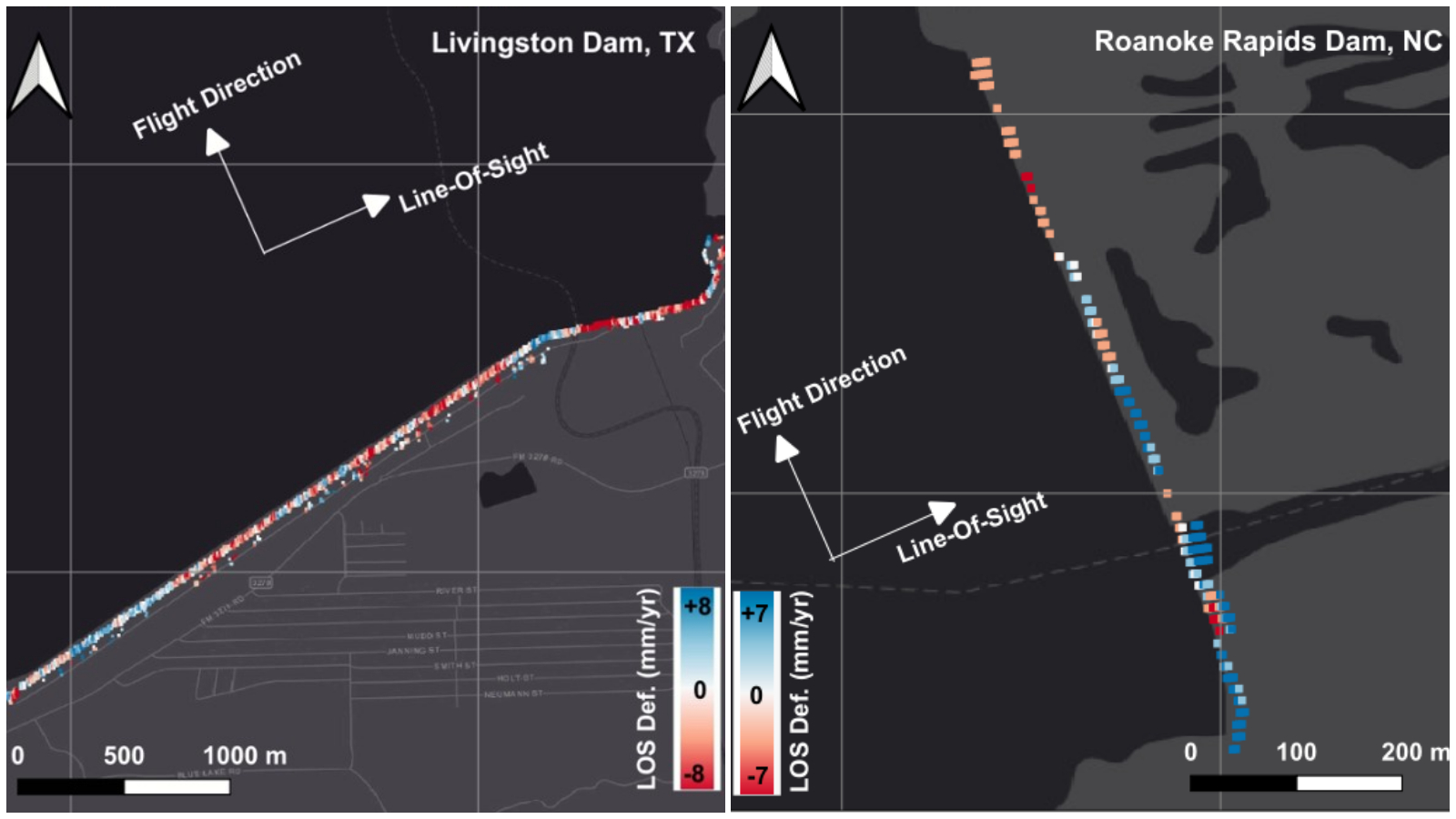

Results are preliminary and have not been peer-reviewed. Nevertheless, previously unknown weaknesses have been uncovered in dams in 13 U.S. states and Puerto Rico, including the Roanoke Rapids Dam in North Carolina and the largest dam in Texas, the Livingston Dam.

Some of these high-risk dams have been significantly modified. For example, the northern portion of Livingston Dam, which feeds two water treatment plants that serve more than 3 million people in Houston, is sinking at a rate of about 0.3 inches (8 millimeters) per year, while the southern portion is rising by the same amount.

“That doesn’t mean part of the dam is collapsing,” Khorami said. However, he added that such elevation differences can be problematic and require further investigation. Given that these dams are decades old, can have defects, and impact both downstream people and energy supplies, deformation of the structures can have dire consequences.

you may like

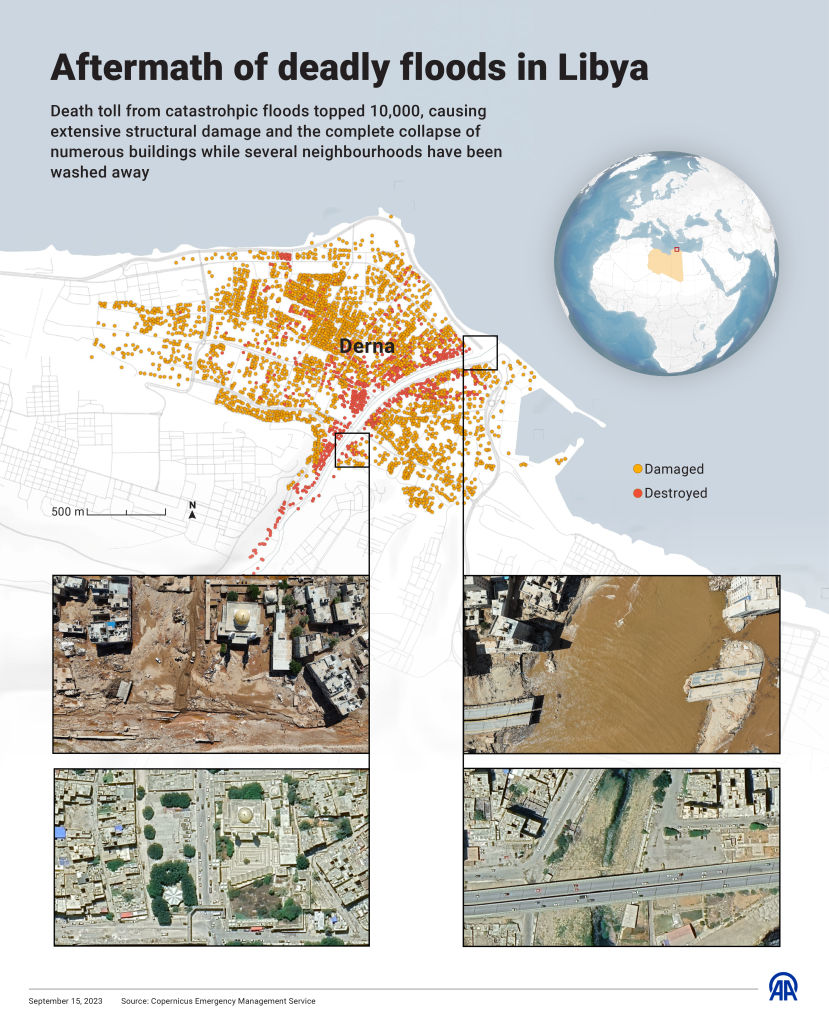

A tragic event in Libya in 2023 suggests that changes in land elevation cannot be ignored. On September 11, two dams collapsed due to extreme rainfall caused by Storm Daniel. The failure released 1 billion cubic feet (30 million cubic meters) of water, or the equivalent of 10,000 Olympic swimming pools, into the city of Derna, destroying buildings and bridges and killing up to 24,000 people.

A 2025 study found that deformation of the dam due to changes in land elevation likely contributed to the collapse. “Satellite image results showed continuous and persistent deformation in both of these dams over the past decade,” Khorami said. “So these dams were already vulnerable.”

Khorami and his colleagues are finalizing their findings. The next step is to create an interactive map or database that policymakers can use to assess the safety of U.S. dams.

“This is not a replacement for testing,” Khorami said. “We’re giving you another tool to help you find early warning signs if there’s a problem, or potential problem, with your dam.”

Aging infrastructure, changing climate

But ground movement is just one factor that can put dams at risk. There are approximately 92,600 dams in the United States, of which more than 16,700 are “potentially hazardous,” meaning that a failure could cause loss of life or significant property destruction, according to ASDSO. Most were designed more than 50 years ago, and about 2,500 of them show signs of damage that will cost billions of dollars to repair.

Not all of these are huge like Hoover Dam. In fact, thousands of dams are small watershed dams designed to prevent flooding, provide drinking water, and protect wildlife habitat.

When these dams were built in the 1960s and 1970s, few people lived nearby, so they posed little danger to people. But decades have passed and a community has mushroomed around them, meaning failure can have devastating effects.

Additionally, most of these dams were designed to withstand the environmental conditions at the time they were built, but global warming and land use changes have changed that.

Some rivers are declining due to drought, while other rivers are higher in water levels and flows than they were 50 to 60 years ago, as increased precipitation and urbanization reduce the amount of water stored in the soil, Ebrahim Ahmadisharaf, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Florida State University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

Ahmadisharaf said the weather has also become more extreme and unpredictable, increasing the risk of sudden flooding. In a 2025 study, he and his colleagues found that over the past 50 years, the likelihood of dam overtopping (water levels rising so high that they exceed the capacity of the spillway and spilling over the dam) has increased for 33 dams.

The dams in the study that had the highest overflow rates were large dams with relatively large populations living in cities and small towns downstream, such as the Whitney Dam in Texas, Milford Dam in Kansas, and Whiskeytown Dam in California. Populous areas that could be affected include Waco, Texas, with a population of 150,000, and Junction City, Kansas, with a population of 22,000.

“Overflowing is a possible dam failure mechanism,” Ahmadi-Sharaf explained. “It can cause catastrophic flooding downstream and even lead to structural failure. The larger the dam and the shorter the distance to downstream infrastructure and people, the greater the risk.” [overtopping is]. ”

money problem

One of the biggest hurdles to making America’s dams safer is funding. The older the dam, the higher the bill.

“Operating, maintaining and repairing dams can cost anywhere from a few thousand dollars to millions of dollars, and the responsibility for these costs lies with owners, many of whom are unable to pay these costs,” Roche said. “Repairing just the most important dams is estimated at $37.4 billion, and that cost continues to rise due to delays in maintenance, repairs, and rehabilitation.”

Deploying satellite monitoring of dams would increase the financial burden, but it could be worth the cost if it helps prioritize remediation and prevent dam failures, Roche said. Traditional inspections of dams do not always identify significant structural problems, according to a forensic report into the 2017 Oroville Dam spillway incident that displaced more than 180,000 people but caused no deaths.

Roche said it is difficult to determine whether using satellite data to prioritize dam repairs is useful because only preliminary results are available so far. But theoretically, “deformation of the dam structure could indicate a problem or worsening condition,” he said.

David Bowles, an expert on dam safety risks and professor emeritus of civil and environmental engineering at Utah State University, is more skeptical. “There are many different ways a dam can fail,” Bowles told LiveScience in an email. “In my experience, foundation subsidence is not the primary root cause of dam failures, but it can be a contributing factor, especially if it is not monitored or managed.”

Ahmadi-Sharaf said satellites could also play a role in assessing the risk of dams overflowing. Satellite radar images could provide more accurate estimates of water levels and flooding, which could help spread warnings earlier.

Overall, Ahmadi-Sharaf said, satellites could provide a broader picture of dam risks than we currently know. “We can’t monitor everywhere, but satellites provide that opportunity,” he said.

Source link