European folk healers in the 16th century left their manuals smeared with ingredients and fingerprints as they developed treatments for minor illnesses. Researchers are now studying the chemical traces left behind by Renaissance people to understand how they experimented with new treatments.

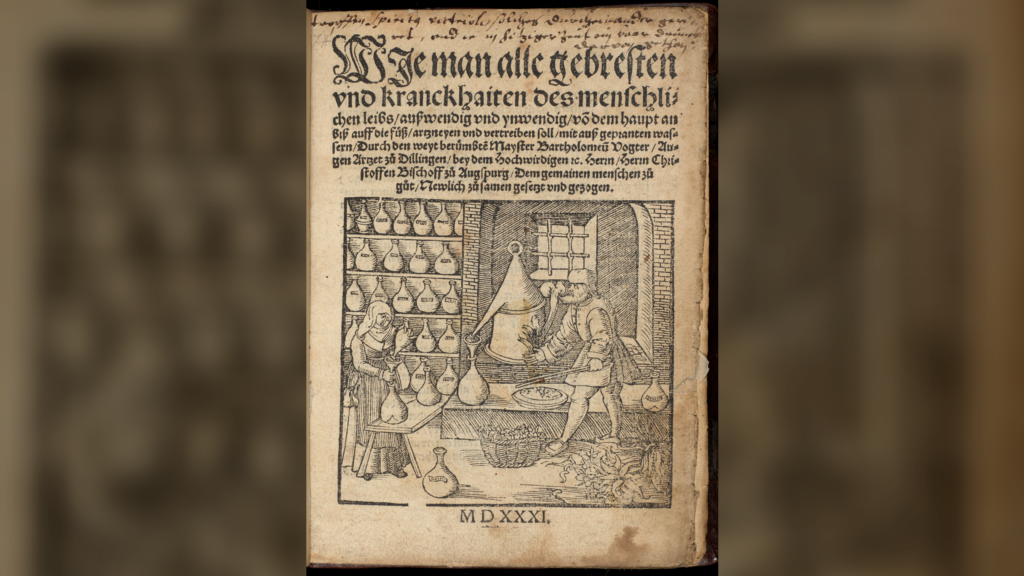

Two German medical books, How to Cure and Eliminate All Sufferings and Diseases of the Human Body and A Handy and Essential Little Medical Book for the Common Man, were published in 1531 by ophthalmologist Bartholomeus Vogtell. His recipe books, which systematically collected common ailments such as hair loss and bad breath, quickly became Renaissance family medicine bestsellers.

you may like

In a study published Nov. 19 in the journal American Historical Review, researchers reported that they were able to use proteomic analysis to identify the materials that doctors used to flip through Vogueser’s books centuries ago.

“When people touch paper, they always leave molecular traces on the pages of books and other documents,” study co-author Gleb Zilberstein, a biotechnology expert and inventor, told Live Science via email. “These traces include components of sweat and in some cases saliva, metabolites, pollutants, and environmental components.” Proteins and peptides are part of this mixture, “often invisible to the naked eye,” Zilberstein added.

To analyze the proteins and peptides (molecules made up of strings of amino acids), the researchers first used specially made plastic diskettes to capture the proteins from the paper. They then used mass spectrometry to detect individual amino acid chains that could be identified as specific proteins.

The researchers sequenced a total of 111 proteins from the Vogtherr manual. The researchers wrote that most of the proteins were obtained from healthcare workers themselves, but some were related to plants and animals that appear in therapeutic recipes.

The researchers wrote that “trace of European beech, watercress, and rosemary peptides were detected next to recipes recommending the use of these plants to cure hair loss and promote hair growth on the face and head,” and “lipocalin was recovered next to recipes recommending the daily use of human feces to wash bald heads to overcome the points of hair loss for reader practitioners following such instructions.”

Other collagen peptides were difficult to identify. One of the extracted proteins could be matched to either a turtle shell or a lizard. Medical texts from the 16th century report that turtle shells can treat edema (fluid retention), while powdered lizard heads were used to prevent hair loss. But the protein was found on the page next to Vogsell’s hair-growth recipes, suggesting users of the medical book may have been experimenting with lizards as a hair-care therapy.

Another surprising discovery was the recovery of collagen peptides that could be matched to kava, next to a recipe that discussed diseases of the mouth and scalp. Hippos were a popular curio throughout early modern Europe, and their teeth were thought to cure baldness, severe dental problems, and kidney stones. Traces of hippo protein may suggest that Voguesell readers are suffering from dental problems, the researchers wrote, with recipes for curing bad breath, canker sores and black teeth annotated in the instructions with dog ears.

“Proteomics can help contextualize both the symptoms people were likely struggling with when they sought help from recipe knowledge, and the physical effects of recipe trials and treatments,” the researchers wrote.

Scientists hope new analysis of invisible proteins stuck to centuries-old books will contribute to a better understanding of early modern domestic science.

“In the future, we plan to expand this study and examine other history books,” Zilberstein said, adding, “We also plan to identify individual readers based on proteomic data.”

Conspiracy Theory Quiz: Test your knowledge of unsubstantiated beliefs, from flat Earth to lizard men

Source link