Few other universe visitors capture the charm of astronomers, like Interstellar Comet 3i/Atlas. This icy wanderer, running through the solar system from the depths of interstellar space, is just the third known object of its kind, and where it came from remains a mystery.

Since its discovery on July 1, 2025, scientists, part of the project, which is part of the Atlas (Asteroid Terrestrial Impact Trastor Alt System) project of the Chilean Deeprandam Survey, pointed to the telescope as experts to visitors, and the public is eager to see it for a more meticulous look. Even the NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and James Webbspace Telescopescope have recently been able to catch a glimpse of this icy comet as they continue to move towards our sun.

So when I heard that Chile’s Gemini South Observatory was holding a live webcast event, I’m working to bring the public to the foldable public of real-time research as part of the Shadow the Scientist (STS) initiative – I knew I had to participate. From the moment the live stream session began, astronomers began calibrating the telescope, so me and the other participants were thrown into the control room in Gemini South. The team had planned to use GMOS (Gemini Multi-Object Spectrographs) and new Gemini High-Resolution Optical Spectrographs (Ghost) instruments to measure the chemical composition of the 3i/Atlas.

Karen Meech, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii’s Astronomical Institute, reminded the audience that such rare occasions are “a component of other solar systems that have been accidentally driven out of the stars by chance.”

Related: New photos of Interstellar Comet 3i/Atlas reveal that their tails are growing in front of their eyes

You might like it

Other experts added to Meech’s point and said they must ask the director of Gemini South Observatory if this particular time can be held away from other observers. You can view the event recordings at the link below.

While Meech took the stage, the Chilean telescope team prepared a massive 26-foot (8-meter) mirror for its delicate work. Inside the control room, scientific operations experts taught me the window of the process. “We’ve taken the calibration, adjusted the telescope and checked the sky. It’s very dry tonight, with a stable wind and great looking.”

The comet was pasted with me. It was only recently that snow was scattered throughout the area. The Gemini South Observatory had not been hit so badly with rainfall, but its neighbour, the Atacama Large Millimeter/Sub-Millimeter Array (Alma) facility at Chaginant Plateau, had enough snow to temporarily suspend all scientific operations. Thankfully, the snow had melted by the time of the live event, and everything went as smoothly as possible.

As the calibration lasted for an hour, Meech answered questions and hyped the audience when the comet could be discovered.

Before Gemini South began watching, both Hubble and JWST were already watching early. Hubble estimated the comet’s nucleus, or core, to be less than 1.86 miles (3 km) wide, buried beneath a halo of dust and gas. Meanwhile, JWST struggled to see the nucleus due to its halo, revealing that 3i/Atlas appears to be abnormally rich in carbon dioxide. This has led to its predecessor 2i/Borisov being the second interstellar comet ever detected, with much more carbon monoxide.

Meech and others from Gemini South wanted to see if 3i/atlas could actually make sure they had a lot of carbon dioxide and dry ice. Meech explained that the comet’s closest approach to the sun will be October, but at that point it is impossible to find as the comet moves behind the sun. She said NASA scientists are currently debating whether they can temporarily reuse existing spacecraft to observe 3i/Atlas on the other side of the sun and remove this blind spot.

Even if not, observations resume in November when 3i/Atlas reappears from behind the sun, and depending on its activity and chemical composition, it could make the comet appear even brighter as more gases and dust burn. But even if the 3i/Atlas actually brightens up, the windows scientists can study it are still limited.

“If you miss these objects, you’ll never see them again,” Meech said. “They are just passing through our solar system. 1i/’oumuaa is still in our solar system. It’s now near the Kuiper Belt.”

“Oumuamua is the first interstellar object ever discovered in the solar system. Astronomers detected it in 2017.

When the telescope began to spin towards the 3i/Atlas, everyone fell on top of the experts by looking at the shared screen of the scientists in the Gemini South Control Room. Meech previously explained that the first chemical that he wanted to use GMO is cyanide, as it interacts with sunlight.

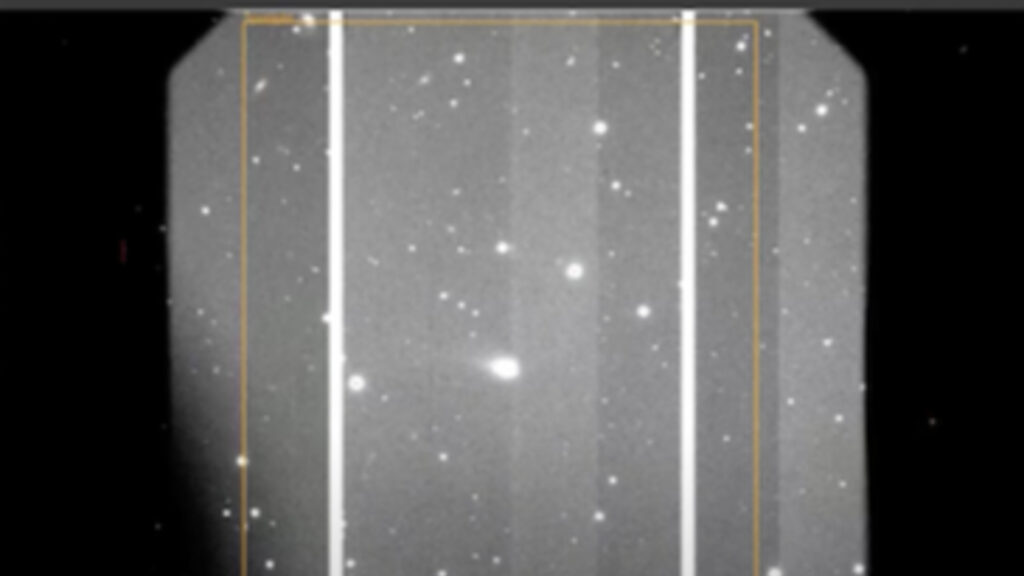

Then came the first image, bright, blurry stains. As we all saw, there was a collective shortness of breath and the event chat was full of surprise and excitement.

“You’re looking at the building blocks of someone else’s house,” Meech said. But she added, “It’s impossible to backtrack a comet based on its trajectory, as everything else is moving around.”

The first image showed faint yet distant glow of the developing tail. This visitor confirmed that it behaved more like a “classic” comet than the strange, elongated ‘oumua’ that Meech also studied.

“This is a raw image,” she said. “If this image is calibrated further, this will have a longer tail.”

In addition to collecting the spectrum, scientists measured the comet’s brightness and compared the reflected sunlight in 3i/Atlas with reference points. This gives rise to estimated color and luminosity, suggesting that 3i/Atlas is faint but steadily active, releasing gas and dust even at considerable distances from the sun.

Before the experts could dive in further, the hosts of the event decided that two hours a night would be sufficient. With the spectrum being captured, brightness measured and many questions unanswered, the session is wrapped in anticipatory notes, and many of us hope to return to the control room of the Gemini South Observatory.

Thankfully, Shadow the Scientists Initiative is planning another public event after 3i/Atlas reappears from the sun. This time I’m using Gemini North Observatory.

Source link