Bowerbirds create a stage to make themselves appear larger to potential partners. Fish and butterflies can flash what appear to be large staring eyes to intimidate predators or deflect attacks. Male peacock spiders raise their legs as part of their courtship ritual, making them appear much larger than they actually are.

These are just some of the strategies that help these animals survive and reproduce. They raise an interesting question: Can animals be fooled by optical illusions?

you may like

Optical illusions are important scientific tools because they reveal the shortcuts the brain uses to transform raw sensory input into perceptions of reality. When something unexpected happens, scientists can gain deeper insight into the rules that govern perception. If non-human animals are the subject of these fantasies, scientists could begin to better understand how evolution has developed similar rules to improve survival and aid reproduction.

“Perception is not about faithfully reproducing reality, but about survival, so many animals use visual strategies such as size exaggeration and camouflage,” Maria Santaca, who studies animal behavior and cognition at the University of Vienna, told Live Science via email.

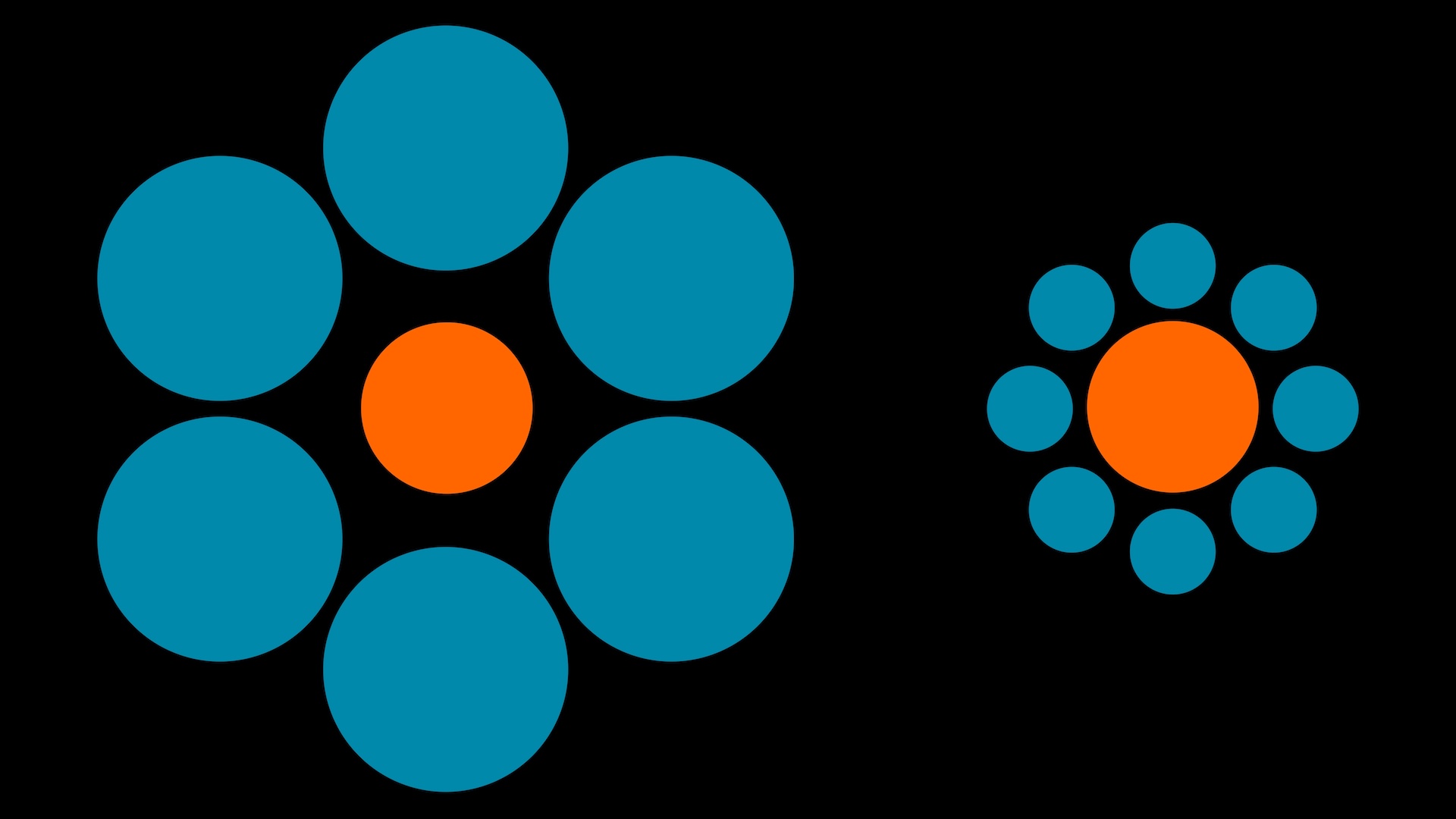

The illusion of size is probably the most well-known visual trick. Humans are always attracted to them. A classic of this genre is the Ebbinghaus illusion, which shows that a single circle surrounded by smaller circles appears much larger than the same circle surrounded by larger circles.

Guppies also fall into this illusion. Santaca was the lead author of a 2025 study that demonstrated that when a circle of bait flakes is surrounded by a smaller disk, fish select them more often, as if there were really more bait inside that circle. In contrast, millet pigeons did not consistently fall into the illusion when tested in the same setting using millet seeds.

Santaca said the likely explanation lies in the two species’ respective ecosystems. “Guppies live in dynamic underwater habitats with changing light and complex backgrounds. Therefore, guppy visual systems emphasize global processing and integrate the entire scene. Pigeons, in contrast, feed on small seeds against textured ground and require accurate local discrimination. Their perception is therefore optimized for detail rather than context, making them less susceptible to this particular illusion.”

Context matters

It turns out that these illusions can be amplified depending on who the animals spend their time with. Female fiddler crabs prefer males with large claws, but attraction is relative. A male surrounded by two smaller clawed rivals is more attractive to females than the same male surrounded by larger male neighbors. This context effect reflects the Ebbinghaus illusion and suggests that men can increase their perceived attractiveness simply by courting their less impressive neighbors.

“These strategies take advantage of the way the visual system interprets context and help animals appear larger to rivals and smaller to predators,” Santanka argued. “What matters in nature is not what appears exactly, but what is perceived in the most advantageous way.”

you may like

Not all species follow the same script. Pigeons are affected by the Ebbinghaus effect, but vice versa, baboons are not affected by the illusion at all. Professor Kelly argued: “This suggests that the brain is wired differently between species, but this is not surprising as there is variation in physiology and the information that is most important may differ between species.”

Not only do animals perceive hallucinations, but some are masters at creating these tricks. “Not only do men use their physical features to make themselves appear larger (and therefore more attractive), they may also use or modify their physical and social environments to change women’s perceptions of their size,” Kelly said.

For example, a 2010 study found that male Great Bowerbirds create forced perspective illusions by lining the floor of their aviaries (places they build to impress females as part of their courtship rituals) with large and small pebbles. Objects that are far away take up less space in your field of vision than nearby objects of the same size. From a woman’s point of view, the fact that this is not true makes the bow look shorter and therefore makes the man look bigger.

Some people are fooled by illusions about their bodies. Octopuses can be fooled by a version of the “rubber hand illusion,” long thought to be unique to humans. In the experiment, the researchers simultaneously stroked the arm of a real octopus, which was hidden from view, and the arm of a fake octopus, which was visible. When the fake arm was pinched, the octopus reacted as if its own arm had been attacked, changing color and retracting. Similar experiments have shown that mice can also be fooled by this illusion. Given the fact that the nervous systems of octopuses and rodents evolved completely separately from ours, it’s even more surprising that they too are subject to illusions.

Camouflage as an illusion

Camouflage provides another example. Destructive coloring uses high-contrast patches toward the edges of the prey’s body to create false boundaries that confuse the predator’s edge detection system. Countershading – common in fish, reptiles, and mammals – involves a gradual change in color from a dark color at the top to a light color at the bottom. Since the sun comes from above, it is believed that a light belly makes it difficult to spot prey from below. Similarly, a 2013 study found that black prey’s backs blend better with dark ground and ocean depths, which is thought to confuse predators hunting from above.

“Countershading is probably so popular because it solves a very fundamental problem: how do you avoid being seen by predators when directed light creates areas of light and darkness across your body,” Kelly said.

In the Ebbinghaus illusion, just as the size is distorted by the surrounding environment, the brightness and color are also distorted by the situation. Gray patches appear darker against a pale background. This is a phenomenon called simultaneous luminance contrast. A similar effect occurs with colors. Insects, fish, and birds all exhibit these biases, suggesting a common mechanism for processing contrasting colors and hues. This illusion may be useful for courting males to make themselves appear brighter, or for animals that change color to stand out from the background.

Illusions show that perception is not about complete accuracy. It’s all about what works in your particular environment. As Kelly told Live Science, “At the end of the day, it’s always about survival and reproduction.”

In the case of guppies, integrating context may help them judge rivals and mates in a flickering stream. For pigeons, precision is preferred over context when pecking seeds. When animals themselves deploy illusions, they utilize these neural shortcuts as a survival strategy. The gap between reality and perception is the richest space for evolution to do its most creative work.

Source link