Archaeologists have discovered a 3,500-year-old military fortress with zigzag walls in Egypt’s North Sinai Desert, near the Mediterranean coast. The fort is surprisingly well preserved, with remains of ovens and fossilized chunks of dough that the fort’s soldiers never had a chance to eat.

Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said in a translated statement that artifacts unearthed from the approximately 2-acre (0.8 hectare) fortress suggest it may have been built during the reign of Thutmose I (c. 1504-1492 BC). Thutmose I was the pharaoh who expanded the Egyptian empire into what is now Syria, which helps explain the location of the fortress.

One of the inner ramparts of the fortress has a zigzag pattern, running from north to south and separating part of the western section that was used as a residential area. Hesham Hussein, Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities’ Undersecretary for Antiquities in Lower Egypt and Sinai, who led the excavation team at the site, told Live Science in an email that the zigzag pattern “helped strengthen the stability of the wall and reduce the effects of wind and sand erosion.”

Some of the outer recesses contained small ovens, which were likely used for “daily household chores within the fortress,” he added. This is near where the team discovered fossilized dough next to one of the ovens.

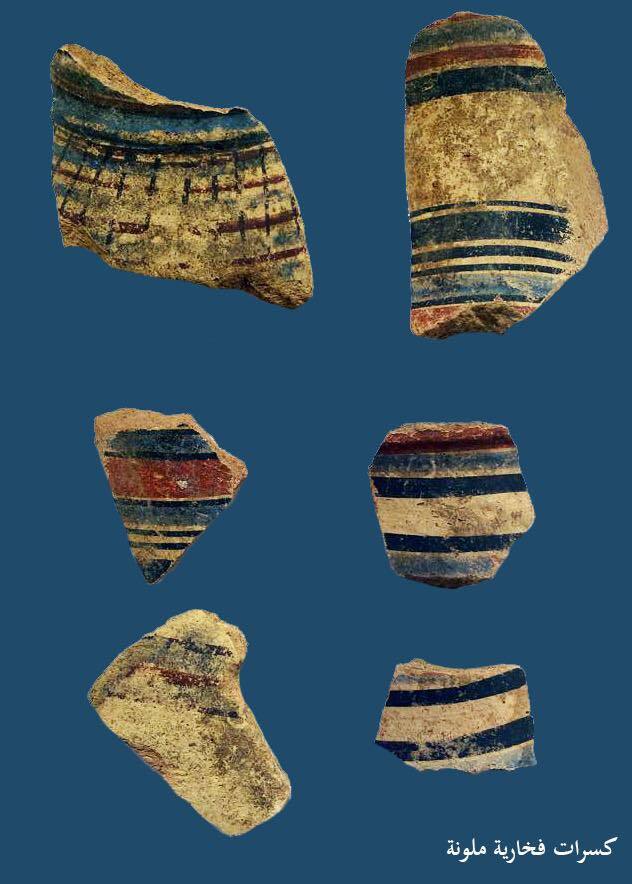

The large fortress was heavily guarded. Archaeologists have so far discovered 11 defensive towers within the fortress, some of which still have “basic deposits” made of pottery buried at the beginning of construction. Some of the pottery is engraved with the name of Thutmose I. In ancient Egypt, foundation deposits were commonly buried as ritual offerings in newly constructed buildings.

Considering its size, the number of soldiers would have been large. “Taking into account warehouses, courtyards and other facilities, the garrison strength is probably in the range of 400 to 700 soldiers, with a reasonable average estimated at around 500 soldiers,” Hussein said.

Archaeologists have discovered soldiers’ residences within the fortress. Inside the fortress they discovered volcanic rock that may have been used in the construction of the Aegean islands. The team is investigating whether there is a nearby port that could help resupply the garrison.

“The discovery of this fort is very exciting,” said archaeologist and professor at Trinity International University James Hoffmeyer. He is currently excavating another fortress at the Tell el-Bog site in the Sinai Desert, but was not involved in the new discovery.

Hoffmeyer told Live Science in an email that the newly discovered fortifications at Tell el Borg and previously discovered fortifications were “part of the military road from Egypt to Canaan that enabled Egyptian control of the eastern Mediterranean coast for most of the fourth century.” He pointed out that Egypt would control the coastline to Canaan for much of the New Kingdom, which lasted from about 1550 BC to about 1070 BC.

The discovery that the newly discovered forts were likely built under the orders of Thutmose I is important because it confirms “the long-held view that Thutmose I was the father of the Egyptian empire in West Asia, and that he likely played an important role in initiating this system of defense, to which his successor kings probably added further forts,” Hoffmeyer said.

Gregory Mumford, an Egyptologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who was not involved in the excavation, told Live Science that research at the site will “significantly expand our understanding of the nature of Egypt’s securing of northeastern Sinai along the ‘Way of Horus’ during the early New Kingdom” and provide more insight into how Egypt defended its eastern borders.

Excavation and ruin analysis are underway at the site.

Ancient Egypt Quiz: Test your smarts about pyramids, hieroglyphs and King Tut

Source link