Skull cups and skeleton masks have been discovered in a 5,000-year-old pile of discarded human bones in China, according to a new study.

The carved skull was found mixed with pottery and animal carcasses, but experts have so far not determined the purpose of the macabre item.

you may like

Several graveyards in Liangzhu have been discovered in the past, but no carved bones were found. Archaeologists recovered more than 50 human bones from canals and moats at five sites, all showing signs of “manipulation” such as cracks, holes, polishing, and tools.

“The fact that many of the processed human bones were discarded in canals unfinished suggests a lack of respect for the dead,” study lead author Sumiaki Sawada, a biological anthropologist at Niigata University of Health and Welfare, told LiveScience via email.

There were no traces of bones from people who had died violent deaths, or any signs of dismembered skeletons. This means the bones were likely disposed of after the corpse had decomposed, Sawada said.

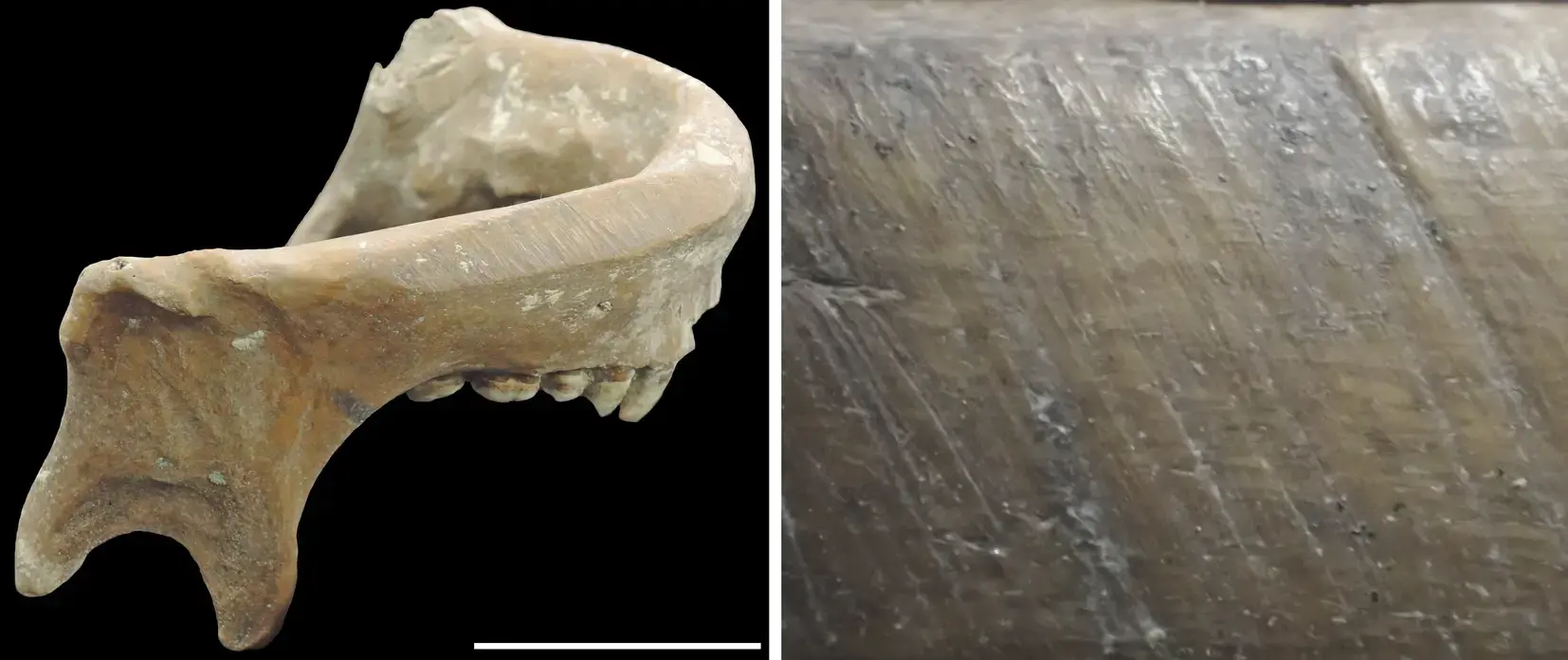

Researchers have found that the most commonly processed bone is the human skull. Researchers found four adult skulls that had been cut or split horizontally to create “skull cups” and another four that had been split vertically to create skeleton mask-like objects.

Human skull cups have previously been recovered from noble burial sites in the Liangzhu culture, suggesting they may have been made for religious or ceremonial purposes, the researchers wrote in the study.

However, there is no similarity in the skull with a mask-like face. Other types of discarded engineered bones are also unique, such as skulls with holes drilled in the back and lower jaws that are intentionally flattened.

“We believe that the emergence of urban society and the accompanying encounters with social ‘others’ beyond traditional communities may hold the key to understanding this phenomenon,” says Sawada.

you may like

The study found that many of the processed bones were unfinished, suggesting that the bones were neither particularly rare nor particularly valuable, highlighting changing perceptions of the dead in the rapidly urbanizing Liangzhu culture. When people no longer knew all their neighbors or counted them as relatives, it could be easier to separate bones from the people they belonged to, the study authors suggested.

“The most interesting and unique thing about this discovery is the fact that the processed human bones were essentially garbage,” Elizabeth Berger, a bioarchaeologist at the University of California, Riverside, told Live Science. Berger agreed with the researchers that the atypical processing of bones may be related to the increased anonymity of urban societies.

The researchers wrote that the custom of human bone processing in the Liangzhu culture appeared suddenly and lasted for at least 200 years, based on radiocarbon dating, before disappearing.

“The people of Liangzhu came to regard human body parts as inert raw materials,” Berger said. “But what caused this to happen, and why did it only last for a few centuries?”

Sawada said future research could help answer these questions, especially by determining when and how people obtained the bones. These additional analyzes could help researchers unravel the meaning behind this practice and its relationship to changes in social bonds and kinship in Neolithic China.

Stone Age Quiz: What do you know about the Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic periods?

Source link