The history of Australia’s First Nations dates back tens of thousands of years and is rich in depth and diversity.

Archaeological research reveals much about this deep past, but does not capture ancestral gestures: movement, posture, or physical movement. Material traces like tools and furnaces tend to survive. Usually, fleeting movements are not.

A newly published study in the Australian Journal of Archaeology revealed something different. Traces of hand movements preserved in deep soft rocks in Gnaikulnai Province.

You might like it

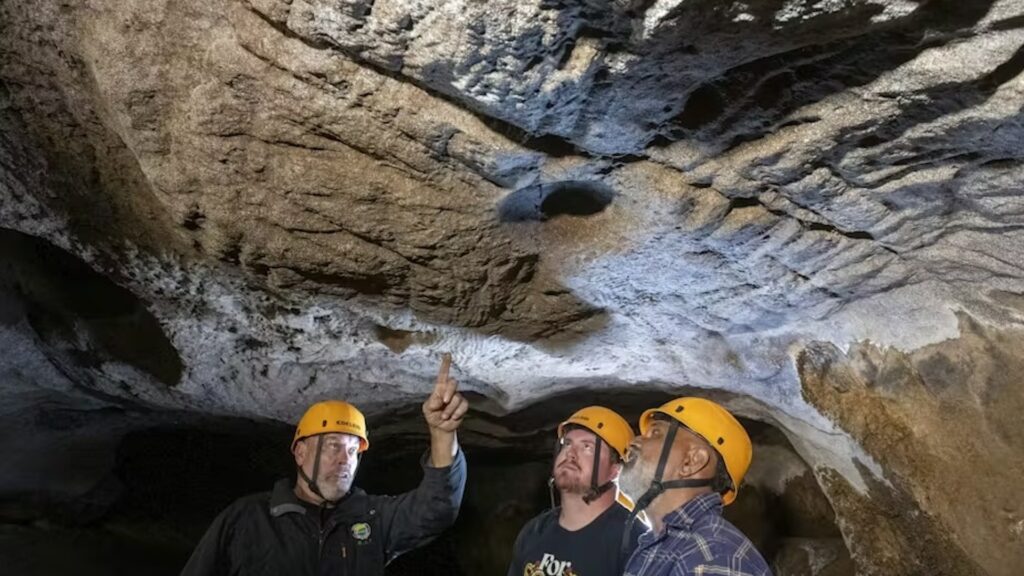

In a limestone cave in the hilly Victorian Alps, we collaborated with team of researchers led by Aboriginal Publishing in the Lands and Waters of Gnaikulnai, and international archaeologists from Spain, France and New Zealand to study the impressions of fingers dragged into walls and ceilings. They reveal the movement of their ancestors’ hands that were thousands of years ago.

Glittering Wali Book

The cave called the Waribruk by the elders of Gunaikurnai contain a black room out of reach of natural light. To enter and mark these walls, the ancestors would have needed artificial light: fires or small fires.

The deeper interior walls of the cave were softened for millions of years as groundwater permeated the limestone, slowly weathered, and dissolved the rock into a spongy tunnel.

The remaining wall surfaces and ceilings became spongy and malleable, just like the theatre’s texture.

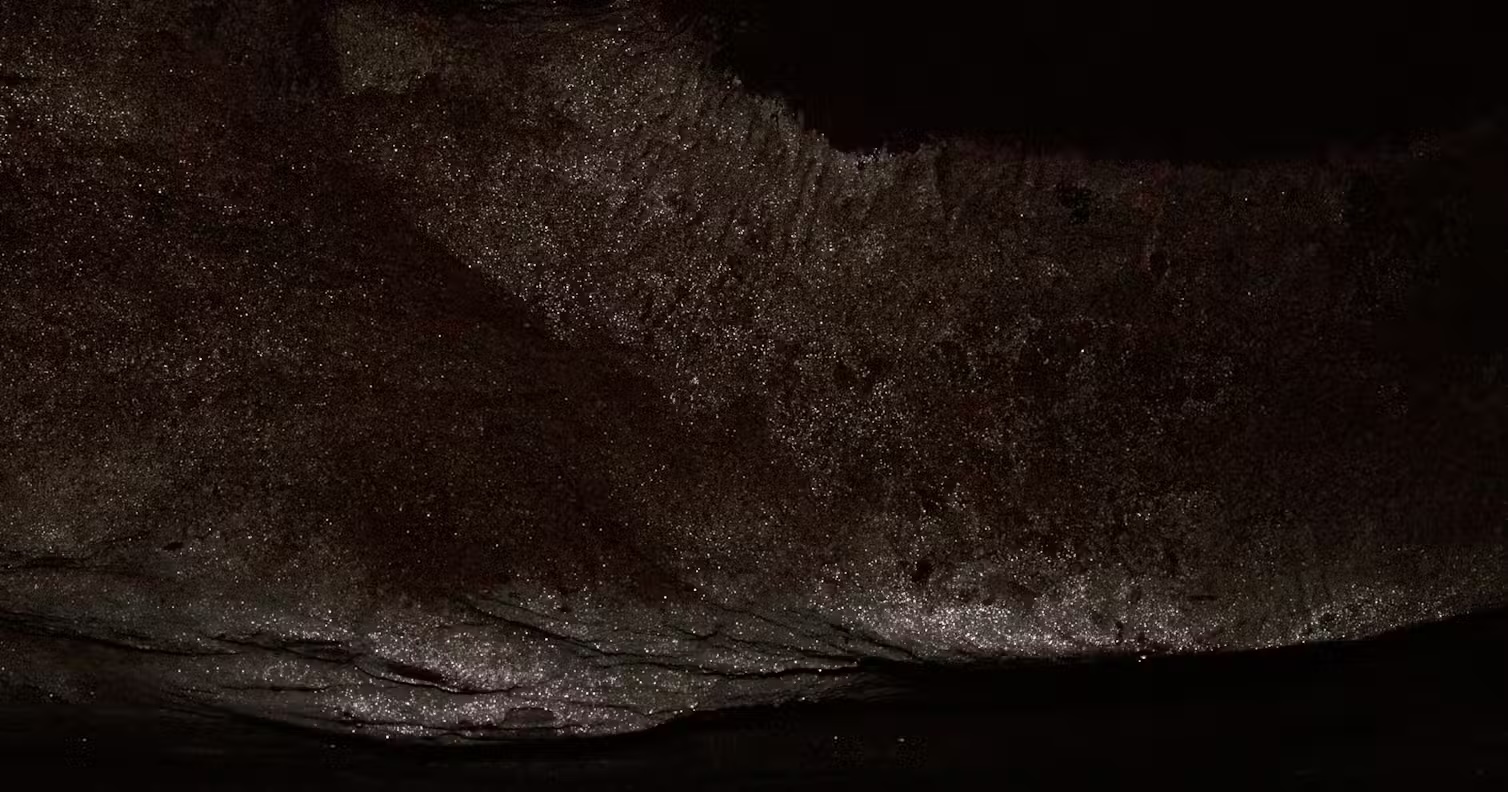

Over time, the bacteria living in caves that live on soft, damp rocks have produced luminescent microcrystals, which today make walls and ceilings lighter when exposed to light.

It is on these glittering surfaces that the finger grooves are found.

It’s not exactly clear when it was made, but people would have needed artificial light to reach this part of the cave. They would have either been on fire or had been on fire on the ground.

Archaeological excavations below and near the panels were unable to reveal evidence of fire in the ground, but found millimeter fragments of small patches of charcoal and small ashes.

They were found to be buried under the decorated walls and on the floor of a cave nearby. They date 8, 400 to 1, 800 years ago, about 420-90 generations ago.

This is the best estimate how long ago, to create a finger impression on the wall when an old ancestor passes through the dark tunnels of a cave and catches fire on the hands.

Unusual ancestor gestures

What they made when they dragged their fingers along the surface of soft rock deep into the cave is amazing, revealing rare evidence of ancestral gestures.

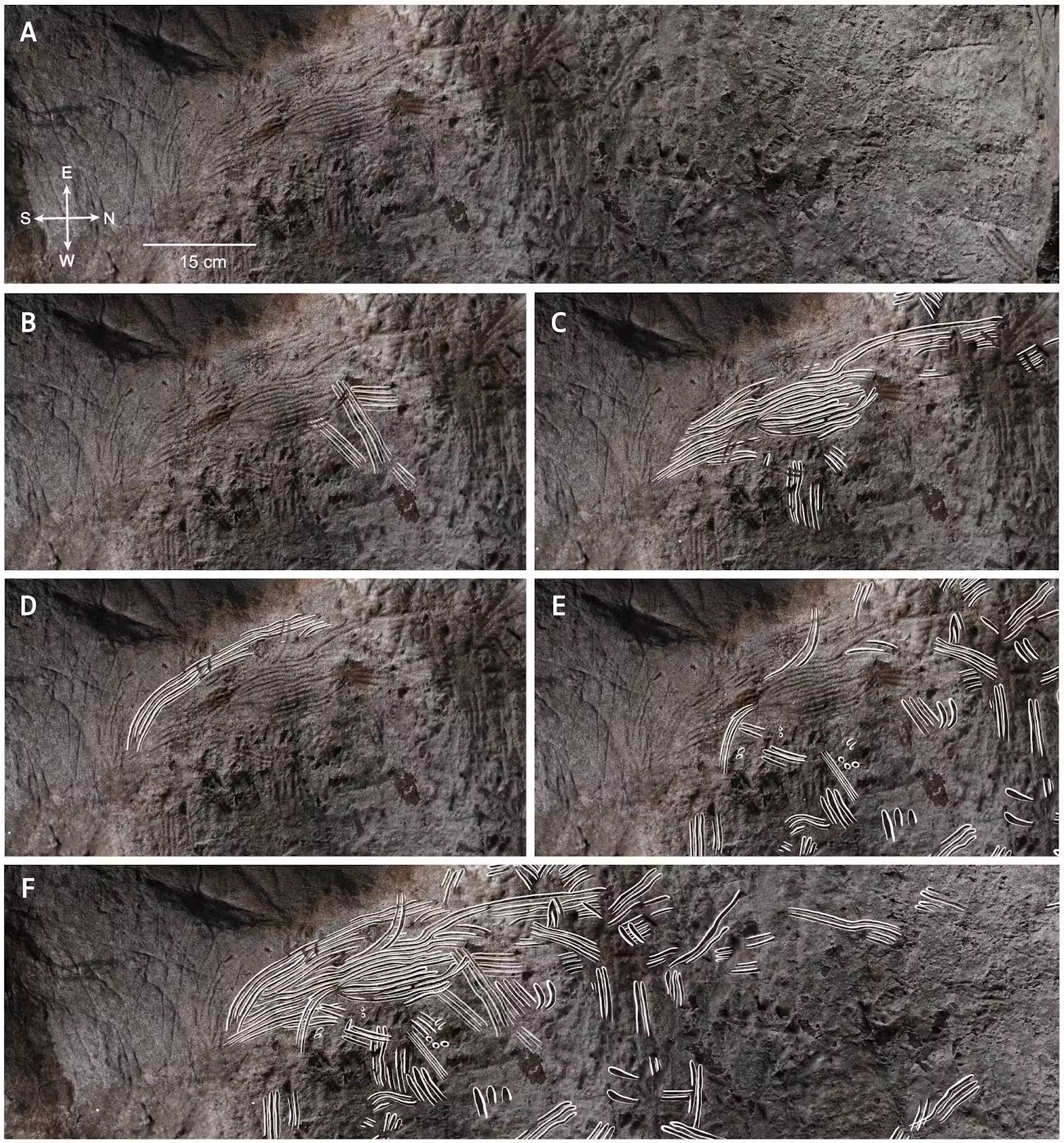

One panel recorded 96 sets of grooves. The first mark is performed horizontally, made with multiple fingers. Later, vertical and diagonal grooves were added, intersecting the previous grooves.

Among them are two parallel sets of narrow impressions, only 3-5 mm [0.1 to 0.2 inches] Each finger is wide. Each of them is set at a short distance, indicating that they were made by small children. But they were very high and the children must have been lifted up by adults.

Deep inside the cave, the low ceiling panels contain 262 grooves above a narrow clay bench that slops sharply towards the creek bed. The grooves indicate people move along the shelf, sitting down, or balanced to reach the ceiling.

Further along, the 193 ditch follows the path above the bed of the stream. I pushed my fingers into the soft ceiling and gradually released 1.6 meters. [5.3 feet] As people move forward, they go even further.

All impressions point to the same thing, capturing an intentional, embodied gesture as the arms and hands are raised above their heads and their ancestors enter the cave deeper.

There are only a few places you can enter

Overall, there are 950 sets of finger grooves deep inside the warbook. Their meanings remained unknown for years, but a close analysis of where the marks appear and where they do not present offers important insights.

The groove is always in the area where calcite crystals cover the walls and ceiling of the cave, and sometimes just pass by the edge of the sparkling. It never appears in the cave area with no sparkle on soft walls.

Importantly, they are far from the archaeological evidence of family life. There is no hearth, no food left, and no tools.

This absence is important. The oral tradition of Gunaikurnai believes that such caves are not used in ordinary life. They were visited frequently only by special individuals, Mulla-Mullung.

Mulla-Mullung used crystals and powdered minerals as part of his practice to heal and curse the ritual.

In the late 1800s, Gunaikurnai knowledge holders spoke to the pioneering ethnographic version of Alfred Howitt about the power of these crystals and caves. They explained, the role of Mura Murun was usually passed on from parents to children, and when Mura Murun lost their crystals, they lost their strength.

The grooves in the fingers of the Waribruk match these traditions. They are not casual decorations. They are intentional gestures linked to crystal-coated surfaces, made in places where only a few can enter.

The groove reflects a source of movement, touch, and power for special individuals in the community.

It’s not just ancient “rock art” that survives. These are ancestor gestures, and it appears that Mura Murun has now accessed the glittering powers of the surface, challenging the deepest darkness of the cave.

Through these finger trajectories, we can get a glimpse into cultural practices based not only on physical actions, but also on knowledge, memory and spirituality. The instantaneous movements preserved in stone and linking us to life that lived long ago bring the cave back to life through the actions of our ancestors and cultures.

Acknowledgements: The authors are three of the 13 authors of the journal article, and Olivia Libero Villa and Diego Gallate Mydaghan took on the photos and created digital 3D models of the panels to record and measure the size of the finger grooves.

This edited article will be republished from the conversation under a Creative Commons license. Please read the original article.

Source link