The frigid conditions on the surface of Saturn’s largest moon Titan allow simple molecules in the atmosphere to break one of chemistry’s most fundamental rules, a new study shows.

According to this principle, known as “like dissolves like,” mixtures containing both polar and nonpolar components, such as oil and water, typically do not mix and form separate layers.

you may like

“This contradicts the chemical law of ‘like dissolves like,’ which basically means that it is impossible to combine these polar and non-polar substances,” lead study author Martin Rahm, associate professor of chemistry, biochemistry and chemical engineering at Chalmers University of Technology, said in a statement.

The new research, published July 23 in the journal PNAS, challenges a long-standing pillar of chemistry and could open the door to the discovery of more exotic solid-state structures throughout the solar system.

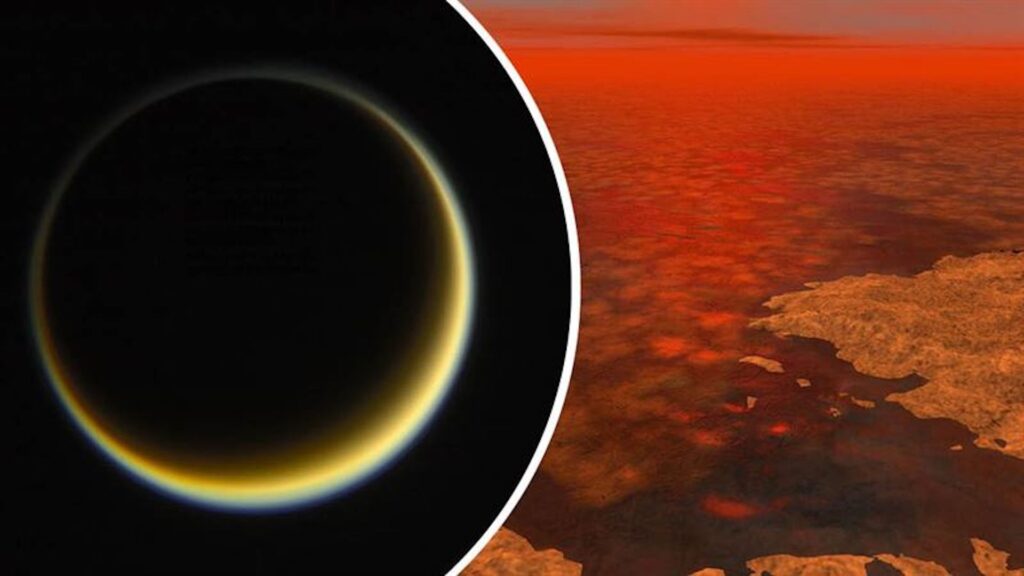

Reproducing the surface of Titan

Research shows that conditions on Titan’s surface are strikingly similar to conditions on early Earth. Its atmosphere contains high levels of nitrogen and the simple hydrocarbon compounds methane and ethane, which circulate in local weather systems much like Earth’s water cycle.

But until now, researchers weren’t sure about the fate of the hydrogen cyanide produced by this atmospheric reaction. Is it deposited on the surface as a solid? Do you react to your surroundings? Or could it be transformed into the first molecules of life?

To investigate these questions, the NASA team recreated conditions on Titan’s surface by mixing a mixture of methane, ethane, and hydrogen cyanide at temperatures around -297 degrees Fahrenheit (-183 degrees Celsius). Spectroscopy, a method of studying chemicals through their interaction with light of different wavelengths, yielded unexpected results that suggested that these contrasting compounds were interacting much more closely than previously observed.

Nonpolar molecules of methane and ethane appear to have slipped into the cracks of hydrogen cyanide’s solid crystal structure, a process known as intercalation, forming an unusual cocrystal containing both molecules.

Polar and nonpolar molecules usually do not mix. Polar compounds such as water and hydrogen cyanide have charge distributed unevenly throughout the molecule, with some regions being slightly positive and some regions being slightly negative. These oppositely charged regions are attracted to each other, forming strong intermolecular interactions between molecules of different polarity, while nonpolar components are largely ignored.

you may like

On the other hand, nonpolar oils and hydrocarbons have completely symmetrical charge configurations, have very weak interactions with neighboring nonpolar molecules, and do not interact with polar particles at all. As a result, mixtures containing both polar and non-polar components, such as oil and water, usually form distinct layers.

To explain their strange observations, the NASA team collaborated with researchers at Chalmers University of Technology to model hundreds of potential cocrystal structures and assess the likelihood of stability of each under Titan’s conditions.

“Our calculations predicted that not only would the unexpected mixture be stable under Titan’s conditions, but the light spectrum would also match NASA’s measurements well,” Rahm explained.

Their theoretical analysis identifies several possible stable crystal forms, which they propose are stabilized by a surprising increase in the strength of intermolecular forces within the hydrogen cyanide solid caused by this mixing.

Their rigorous combination of theory and experiment impressed planetary scientist Athena Kustenis of France’s Paris-Meudon Observatory. She is excited to see how future data, including data from NASA’s Dragonfly spacecraft, scheduled to arrive at Titan in 2034, will complement the research findings.

“Comparing the laboratory spectra with data from the upcoming Dragonfly mission may reveal signatures of these solids on Titan’s surface and provide insight into their geological role and potential importance as a low-temperature prebiotic reaction environment,” Kustenis told Live Science in an email. Further research could extend this approach to other molecules thought to be produced by Titan’s atmosphere, such as cyanoacetylene (HC3N), acetylene (C2H2), hydrogen isocyanide (HNC), and nitrogen (N2), she said. “[This] We plan to test whether such mixing is a general feature of Titan’s organic chemistry. ”

Source link