Researchers have discovered more than 111,000 spiders living in what is believed to be the world’s largest spider web, deep inside a pitch-black cave on the Albanian-Greece border.

This is the first evidence of colonial behavior between two common spider species, and probably represents the world’s largest spider web, said study lead author István Ulak, associate professor of biology at Transylvania Sapientia Hungarian University in Romania.

you may like

“The natural world still offers us countless surprises,” Ulak told Live Science via email. “If I were to try to put into words all the emotions that welled up within me, [when I saw the web]Emphasize admiration, respect, and gratitude. To really know what it feels like, you have to experience it. ”

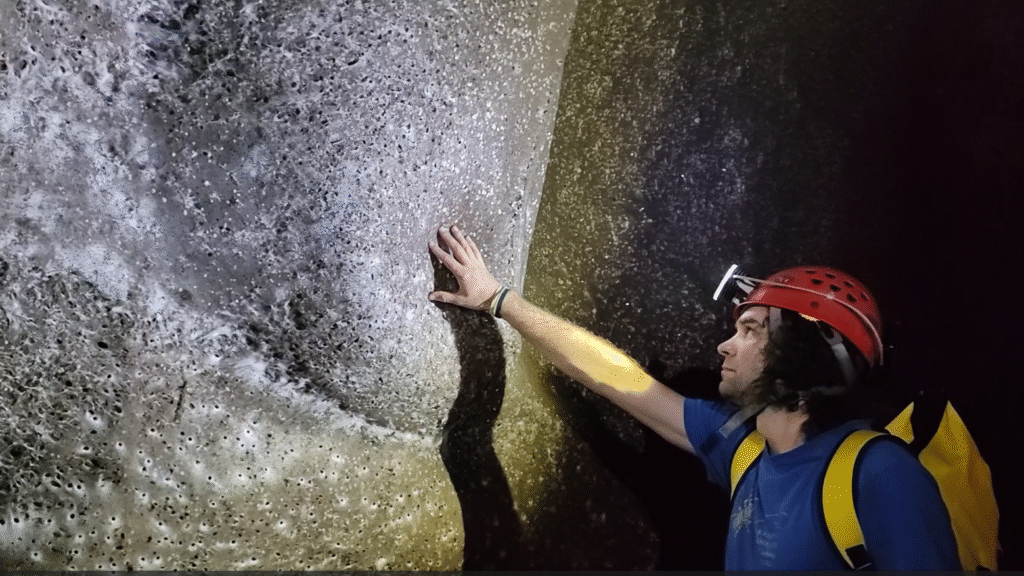

This spider megacity is located in Sulfur Cave, a cave hollowed out by sulfuric acid formed by the oxidation of hydrogen sulfide in groundwater. Researchers have uncovered interesting new information about the Sulfur Cave spider colony, but they aren’t the first to see the giant web. Cave explorers from the Czech Speleological Society discovered it in 2022 during an expedition to the Vromoner Valley. A team of scientists then visited the cave in 2024 and took specimens from the web, which Urak analyzed before setting off on an expedition to Sulfur Cave.

This analysis revealed that the colony was home to two species of spiders. One is Tegenaria domestica, also known as the barn funnel weaver or house spider, and Prinerigone vagans. After visiting the cave, Urak and his colleagues estimated that there were about 69,000 T. domestica and more than 42,000 P. vagans specimens. DNA analysis for the new study also confirmed that these were the predominant species in the colony, Urak said.

The Sulfur Cave spider colony is one of the largest ever recorded, and related species have never before been known to come together and work together like this, Urak said. Although T. domestica and P. vagans are widely distributed near human habitations, this colony is “a unique case of two species coexisting in such vast numbers within the same nest structure,” he said.

Scientists would normally expect barn funnel weavers to prey on P. vagans, but the lack of light inside the cave could impair the spiders’ vision, the study said.

Instead, spiders eat midges that don’t bite, but midges prefer to feed on the white microbial biofilm of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in caves, a slimy secretion that protects microorganisms from environmental threats. Sulfur-rich rivers fed by natural springs flow through the sulfur caves, filling them with hydrogen sulfide and helping microorganisms, midges and their predators survive, the researchers said in a study report.

Gut content analysis revealed that the spiders’ sulfur-rich diet affected their microbiota, resulting in significantly reduced microbiome diversity compared to the microbiota of the same two spider species outside the cave. The molecular data also showed that cave spiders are genetically distinct from their outside relatives, suggesting that cave dwellers are adapted to their dingy environments.

“Oftentimes we think we know the species perfectly and understand everything about it, but unexpected discoveries can still occur,” Ulak says. “Some species exhibit remarkable genetic plasticity, but this is usually only apparent under extreme conditions. Such conditions can induce behaviors that are not observed under ‘normal’ circumstances.”

Mr Ulak said it was important to preserve the colony despite the challenges that could arise from the cave’s location between the two countries. In the meantime, researchers are working on another study that will reveal more clues about Sulfur Cave’s inhabitants, he added.

Source link