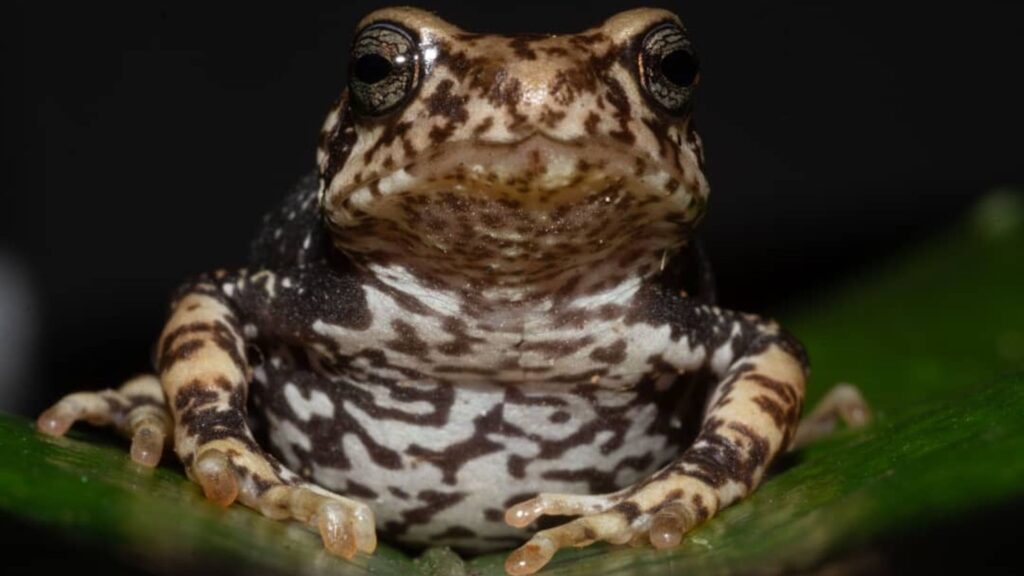

Scientists have identified three new species of toads that do not lay eggs, but live ‘toads’.

All three species are part of the genus Nectophrynoides, also known as “tree toads,” a group known for giving birth to live toad babies that skip the tadpole stage. Previously thought to be a single species with large populations and ranges, these smaller, more fragmented species may require additional conservation measures, researchers said in a new study.

you may like

Prior to this study, only 17 of the more than 7,000 known species of frogs and toads were known to give birth to live young, 13 of which belonged to the genus Nectophrynoides. A new study published Nov. 6 in the journal Vertebrate Zoology adds three newly identified species to their respective totals.

Researchers first identified the species called N. viviparus in 1905 and classified it into the genus Nectophrynoides in 1926. Since then, scientists have discovered specimens of N. viviparus in Tanzania’s Eastern Arc Mountains and Southern Highlands. However, a 2016 study suggested that many of these toads are genetically distinct enough that they may originate from multiple similar but distinct species.

In the new study, researchers took a closer look at the Nectophrynoides toads of the Eastern Ark Mountains. They studied hundreds of toad specimens kept in museums and recordings of wild toad calls. They also sampled mitochondrial DNA from some of the museum specimens using methods known collectively as musiomics.

Taken together, these studies revealed that the local toads actually come from four different species, three of which were previously unidentified. These species (Nectophrynoides saliensis, Nectophrynoides luhomeroensis, Nectophrynoides uhehe) are similar to N. viviparus. However, slight differences in genetics, head shape, and shoulder gland shape and location distinguish them. Other toads that live farther north in the mountains may constitute further new species, the scientists said.

“Some of these specimens were collected more than 120 years ago,” study co-author Alice Petzold, an evolutionary scientist at the University of Potsdam in Germany, said in a statement. “Our museum science research has allowed us to determine exactly which populations these ancient specimens belonged to, giving us even more confidence in future research on these toads.”

Researchers previously believed that N. viviparus was widely distributed in the Eastern Arc Mountains and Southern Highlands and was not considered vulnerable or endangered. However, the discovery that the habitats of these four different species are much smaller and more fragmented could change their conservation status, as each species may be more at risk than expected. One closely related species, Nectophrynoides asperginis, became extinct in the wild in 2009 due to the construction of a nearby dam and the outbreak of a fungal disease.

“The forests that these toads are known to inhabit are rapidly disappearing,” study co-author John Raikuruwa, a biologist at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, said in a statement. These habitats are vulnerable to both human use and climate change.

Future research could help scientists determine how threatened each species is and inform possible conservation strategies, the researchers wrote in the study.

Source link