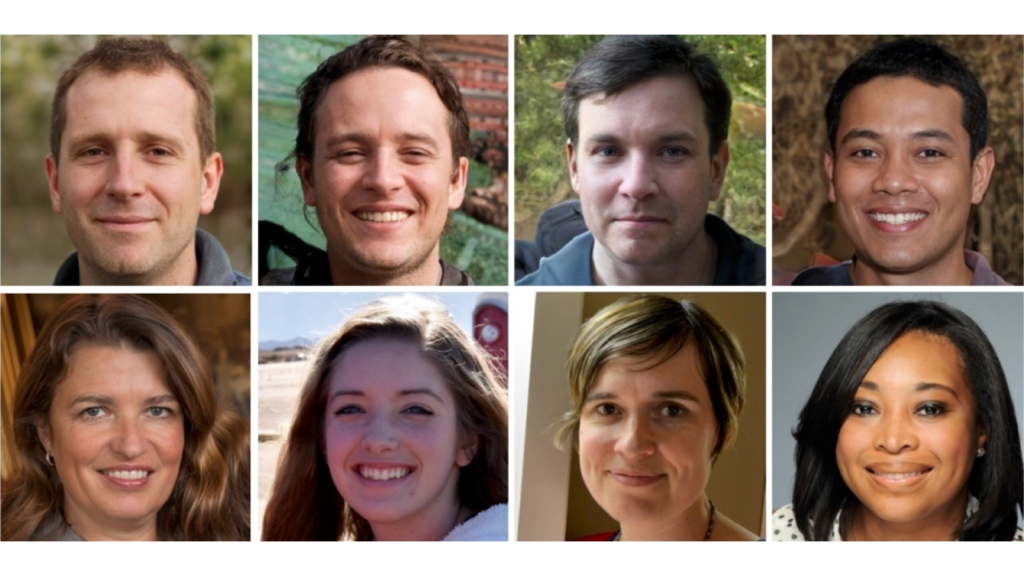

Facial images generated by artificial intelligence (AI) are so realistic that it is only by chance that even an elite group of “super-recognizers” with extremely powerful facial processing abilities can detect fake faces.

People with typical cognitive abilities are worse than chance, most of the time assuming that AI-generated faces are real.

you may like

“I think it’s encouraging that a very short training procedure like ours improved the performance of both groups so much,” the study’s lead author Katie Gray, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Reading in the UK, told Live Science.

Remarkably, this training improved the accuracy of super-recognizers and typical recognizers by the same amount, Gray said. Since the superrecognizer is good at finding fake faces at baseline, this suggests that the superrecognizer relies on a different set of cues to identify fake faces, rather than simply rendering errors.

Gray hopes that in the future, scientists will be able to take advantage of Super Recognizer’s enhanced detection skills to better discover AI-generated images.

“To most effectively detect synthetic faces, AI detection algorithms could potentially be used in a human-involved approach, where humans are trained SRs. [super recognizer]” the authors wrote in their study.

Deepfake detection

AI-generated images have come under an onslaught online in recent years. Deepfake faces are created using a two-stage AI algorithm called a generative adversarial network. First, a fake image is generated based on a real-world image and then vetted by a discriminator that determines whether the resulting image is real or fake. Through repetition, the fake image becomes realistic enough to pass the discriminator.

These algorithms have now been refined to the point where people can be fooled into thinking that fake faces are more “real” than real faces, a phenomenon known as “hyperrealism.”

As a result, researchers are now trying to design training regimens that can improve the AI’s ability to detect individuals’ faces. These trainings point out common rendering errors in AI-generated faces, such as faces with middle teeth, odd-looking hairlines, and unnatural skin textures. It also highlights that fake faces tend to be more proportional than real faces.

you may like

In theory, so-called super-recognizers should be better able to spot fakes than the average person. These super-recognizers are individuals who excel at facial perception and recognition tasks and may be shown two photographs of unfamiliar people and asked to identify whether they are the same person. However, so far, few studies have investigated the ability of superrecognizers to detect false faces and whether their performance can be improved with training.

To fill this gap, Gray and her team ran a series of online experiments that compared the performance of a group of super-recognizers to general recognizers. The super recognizer was recruited from the Greenwich Face and Voice Recognition Laboratory’s volunteer database. They performed in the top 2% in tasks where they were shown unfamiliar faces and had to remember them.

In the first experiment, images of faces, either real or computer-generated, were displayed on a screen. Participants were given 10 seconds to judge whether the face was real or not. The super recognizer’s performance was the same as when it guessed randomly, detecting only 41% of the AI’s faces. Common recognition engines could only correctly identify about 30% of fakes.

Each cohort also differed in how often they thought real faces were fake. This occurred in 39% of cases with super-recognizers and in approximately 46% of cases with general recognizers.

The next experiment was similar, but new participants joined and underwent a 5-minute training session where they were shown examples of AI-generated facial errors. It was then tested on 10 faces to provide real-time feedback on its fake detection accuracy. The final stage of training was a summary of rendering errors to watch out for. Participants then repeated the original task of the first experiment.

Training significantly improved detection accuracy, with the super recognizer detecting 64% of fake faces and the general recognizer noticing 51%. The rate at which each group inaccurately called real faces as fake was about the same as in the first experiment, with the super and standard recognizers rating real faces as “not real” in 37% and 49% of cases, respectively.

Trained participants tended to take longer to scrutinize images than untrained participants, approximately 1.9 seconds slower for the common recognizer and 1.2 seconds slower for the super recognizer. Gray said this is an important message for people trying to decide whether a face they see is real or fake.

However, this test was conducted immediately after training, so it is unclear how long the effects last.

“This training has not been retested and cannot be considered a sustainable and effective intervention,” Meike Ramon, a professor of applied data science and an expert in facial processing at the Bern University of Applied Sciences in Switzerland, wrote in a pre-print review of the study.

Ramon added that because the two experiments used different participants, it is unclear how much training would improve an individual’s detection skills. This requires testing the same people twice, before and after training.

Source link