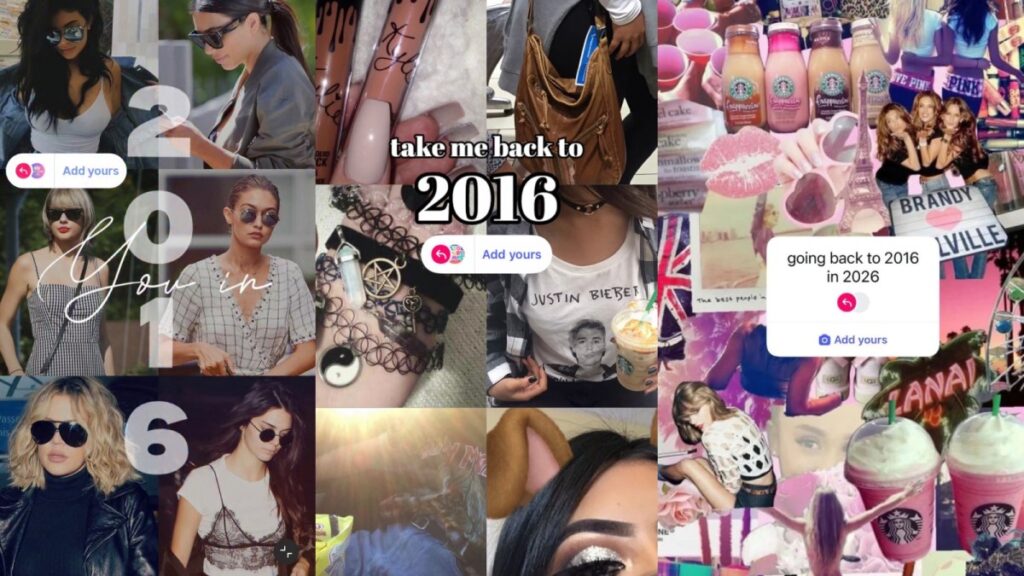

For the new generation, 2016 is known as “the last good year.”

Since the new year, Instagram has been taken over by 2016-themed “add yours” stickers, encouraging users to post throwback photos from 2016. Users have posted over 5.2 million answers, generating enough buzz to spread to other platforms. Spotify has seen a 790% increase in user-created “2016” playlists since the new year, and the company now boasts in its Instagram bio that it’s “Romanticizing 2016 Again.”

In fairness, 2016 seems like a simpler time. Donald Trump hadn’t even worked a day in the White House yet, no one knew the difference between an N95 mask and a KN95 mask, and Twitter was still called Twitter. This year was the year of “Pokémon GO Summer.”

But, as is often the case, much of the anxiety that was already evident at the time is overshadowed by nostalgia. When meme librarian Amanda Brennan searched her archives for images that defined 2016, the screenshots she showed me surprised me, given the internet’s current obsession with the year. “I can’t believe the devil put his all into 2016,” the post read, while another user added: “It’s like I had an assignment due January 1, 2017 and forgot about it until now.”

I forgot how much everyone hated 2016 back then. It was a year of Brexit, the height of the Syrian civil war, the Zika virus, and the Pulse nightclub shooting, to name just a few sources of fear. It wasn’t just President Donald Trump’s polarizing election — that night, a few months earlier, a Slate columnist posed a serious question about how bad 2016 was compared to notoriously bad years like 1348 during the Black Death and 1943 at the height of the Holocaust.

The start of a new year is full of nostalgia. The internet thrives on this kind of engagement fodder, to the point where Facebook, Snapchat, and even the built-in Apple Photos app constantly remind us of what we were doing a year ago.

But this time, our nostalgia feels different, and it’s not just political. As AI increasingly infiltrates everything we do on the internet, 2016 was also just before The Algorithm™ took over, when encitization had not yet reached the point of no return.

tech crunch event

san francisco

|

October 13-15, 2026

To better understand the state of the internet in 2016, Brennan suggests thinking of it as the 10th anniversary of 2006, the year when the social internet became decisively entrenched in our lives.

“Technology changed in 2006. Twitter launched, Google bought YouTube, and Facebook started allowing people over 13 to sign up,” Brennan told TechCrunch.

Before social platforms, the internet was a place for people who searched online for a sense of community, or, in Brennan’s words, “nerds, for lack of a better word.” However, once social media became popular, the internet began to leak, and the barrier between pop culture and internet culture began to disappear.

“By 2016, you could see that 10 years had evolved people. People who weren’t originally internet geeks ended up on 4chan and all these tiny little places that were previously made up of internet people versus people who weren’t really into the internet,” she said. “But thanks to the telephone, it’s like everyone uses the Internet now.”

In Brennan’s estimation, it’s no surprise that 2016 was the year Pepe the Frog, once the amiable webcomic stalker, degenerated into a hate symbol, and the misogyny that fueled GamerGate entered national politics. (Meanwhile, leftist meme groups internally debated whether the “Dat Boy” meme (image of a frog riding a unicycle) was an appropriation of African American vernacular English.)

At the time, it felt novel to point out how internet culture was beginning to influence our political reality. Within another decade, a pseudo-government agency named after the meme was born. To name just one of its many atrocities, international aid funding was cut and hundreds of thousands of people died.

Another 10 years have passed, and we’ve had a full 20 years to reflect on how the social internet has shaped us. But for those who were kids in 2016, it’s still a kind of mystical year. Google worked fine. It was relatively easy to spot deepfakes. Teachers didn’t have to devote all of their limited resources to determining whether students copied and pasted homework from ChatGPT. Dating apps still had high expectations. Instagram didn’t have that many videos. “Hamilton” was cool.

It’s a rosy view of the online age, which has its own turmoil, but it coincides with a larger movement toward a more analog lifestyle. This is the same phenomenon that led to the resurgence of in-person matching events and compact digital cameras. Social media has become so central to our lives that it’s no longer fun and people want to go back to the days before anyone said the words “doomscrolling.” Who can blame them?

Source link