Imagine going to the hospital with a bacterial ear infection and the doctor saying, “There are no other options.” It may sound dramatic, but antibiotic resistance is bringing that scenario closer to reality for more and more people. In 2016, a Nevada woman died from a bacterial infection that was resistant to all 26 antibiotics available in the United States at the time.

In the United States alone, more than 2.8 million cases of antibiotic-resistant diseases occur each year. Globally, antimicrobial resistance is associated with nearly 5 million deaths annually.

you may like

As resistant bacteria become more prevalent, life-saving treatments will face new complications. Common infections are more difficult to treat and routine surgeries are more risky. Slowing these threats to modern medicine requires not only responsible antibiotic use and good hygiene, but also an awareness of how everyday behaviors influence resistance.

Scientists have been sounding the alarm about resistant bacteria since antibiotics were invented in 1910 with the introduction of the synthetic drug salvarsan used to treat syphilis. As a microbiologist and biochemist who studies antibiotic resistance, I believe there are four major trends that will shape how we confront antibiotic resistance as a society over the next decade.

1. Faster diagnosis becomes the new frontier

For decades, treating bacterial infections required a lot of educated guesswork. When a seriously ill patient arrives at the hospital and clinicians don’t yet know the exact bacteria causing the illness, they often start with broad-spectrum antibiotics. These drugs can save lives because they kill different types of bacteria at once, but a variety of other bacteria in the body are also exposed to antibiotics. Some bacteria die, but those that remain continue to multiply and spread resistance genes between different bacterial species. This unnecessary exposure provides an opportunity for harmless or unrelated bacteria to adapt and develop resistance.

In contrast, narrow-spectrum antibiotics target only a small number of bacteria. Clinicians typically prefer these types of antibiotics because they treat infections without disturbing bacteria that are not involved in the infection. However, it may take several days to pinpoint the bacteria causing the infection. During that waiting period, clinicians often feel they have no choice but to begin broad-spectrum treatment, especially if the patient is critically ill.

But new technology could speed up the identification of bacterial pathogens, allowing medical tests to be performed at the patient’s location instead of sending samples off-site and waiting long periods for answers. Additionally, advances in genome sequencing, microfluidics, and artificial intelligence tools have made it possible to identify bacterial species and effective antibiotics to combat them in hours rather than days. Prediction tools can also predict the evolution of resistance.

For clinicians, better testing could help with faster diagnosis and more effective treatment plans that do not worsen resistance. For researchers, these tools demonstrate the urgent need to integrate diagnostics with real-time monitoring networks that can track resistance patterns as they emerge.

Diagnostics alone won’t solve resistance, but it will provide the accuracy, speed, and early warning you need to stay ahead.

you may like

2. Expanding beyond traditional antibiotics

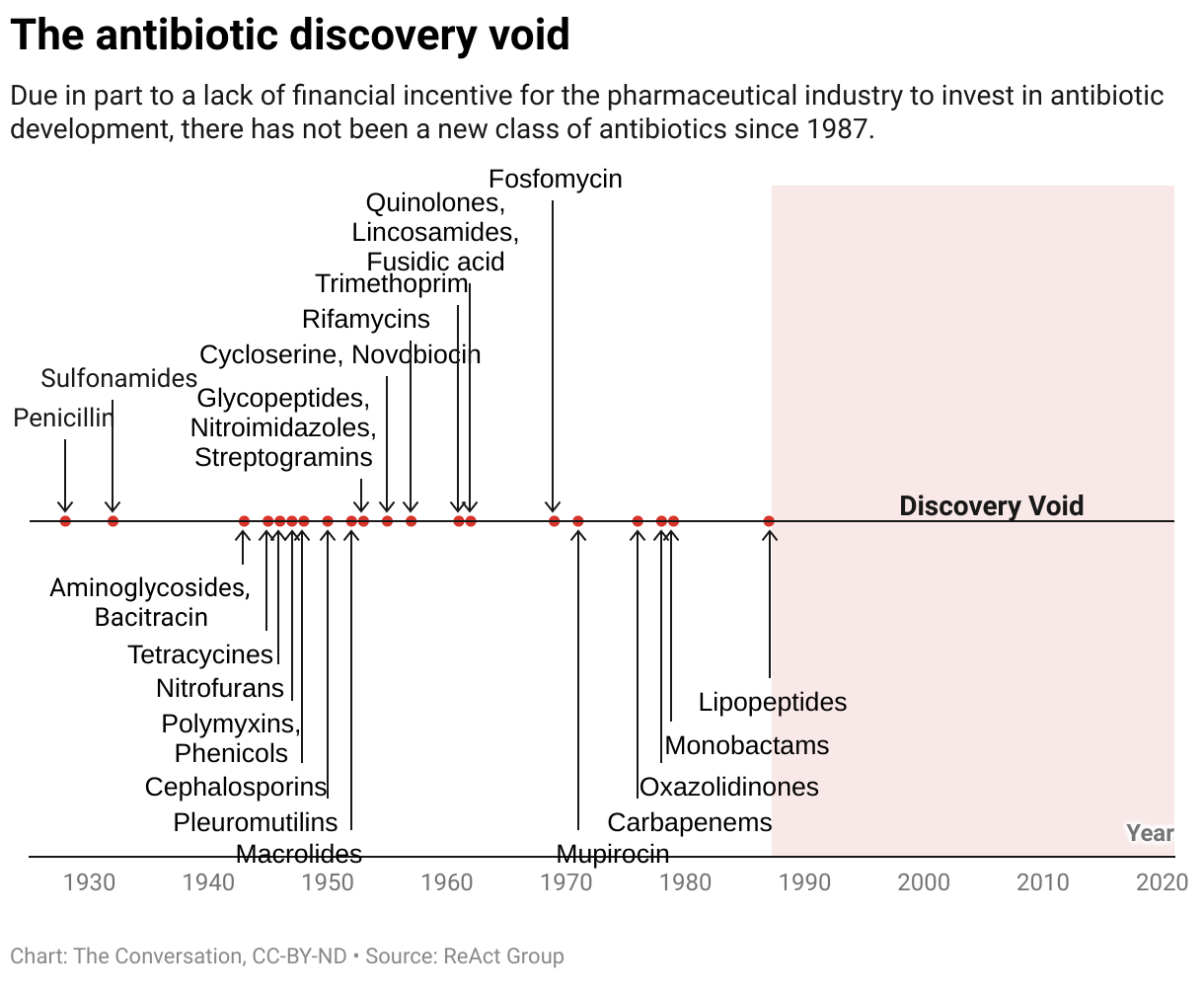

Antibiotics transformed medicine in the 20th century, but relying solely on antibiotics will not survive humanity into the 21st century. The pipeline of new antibiotics remains disastrously thin, and most drugs currently in development are structurally similar to existing antibiotics, potentially limiting their effectiveness.

The gap in antibiotic discovery

To stay ahead, researchers are investing in non-traditional treatments, many of which work fundamentally differently than standard antibiotics.

One promising direction is bacteriophage therapy, which uses viruses to specifically infect and kill harmful bacteria. Some researchers are investigating microbiome-based therapies that restore healthy bacterial communities and eliminate pathogens.

Researchers are also developing CRISPR-based antibiotics that use gene editing tools to precisely disable resistance genes. New compounds such as antimicrobial peptides, which kill bacteria by punching holes in their membranes, hold promise as the next generation of drugs. Meanwhile, scientists are designing nanoparticle delivery systems that transport antibiotics directly to the site of infection with fewer side effects.

Beyond medicine, scientists are investigating ecological interventions to reduce the transfer of resistance genes through soil, wastewater, plastics, and even waterways and major environmental reservoirs.

Many of these options are still in their infancy, and bacteria may eventually evolve around them. But these innovations reflect powerful changes. Rather than betting on finding a single antibiotic to combat resistance, researchers are building a more diverse and resilient toolkit to combat antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

3. Antibiotic resistance outside the hospital

Antibiotic resistance doesn’t just spread in hospitals. It moves through people, wildlife, crops, wastewater, soil, and global trade networks. This broader perspective, which takes into account One Health principles, is essential for understanding how resistance genes move through ecosystems.

Researchers increasingly recognize that environmental and agricultural factors, as well as clinical antibiotic misuse, are key drivers of resistance. These include how antibiotics used in livestock farming create resistant bacteria that spread to people. How do resistance genes in wastewater survive treatment systems and enter rivers and soil? And how farms, sewage treatment plants, and other environmental hotspots become bases for the rapid spread of resistance. Global travel also accelerates the movement of resistant bacteria between continents within hours.

watch on

Taken together, these forces demonstrate that antibiotic resistance is not just a hospital problem, but an ecological and social problem. For researchers, this means integrating microbiology, ecology, engineering, agriculture, and public health to design cross-disciplinary solutions.

4. Policy regarding what types of treatments will exist in the future

Pharmaceutical companies lose money developing new antibiotics. New antibiotics are used sparingly to maintain their effectiveness, so even after the Food and Drug Administration approves an antibiotic, companies often sell too few doses to recover their development costs. Several antibiotic companies have gone bankrupt for this reason.

To encourage antibiotic innovation, the United States is considering major policy changes, such as the Pasteur Act. The bipartisan bill proposes creating a subscription-based payment model that would allow the federal government to pay drug companies up to $3 billion over five to 10 years for access to critical antibiotics, rather than paying per pill.

The World Health Organization, including Médecins Sans Frontières, has warned that the bill should include stronger commitments to accountability and fair access.

Still, the bill represents one of the most important policy proposals related to antimicrobial resistance in U.S. history and could determine what antibiotics will exist in the future.

The future of antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance is sometimes seen as an inevitable catastrophe. However, I believe the reality is more hopeful. In addition to addressing stewardship, society is entering an era of smarter diagnostics, innovative treatments, ecosystem-level strategies, and policy reforms aimed at rebuilding the antibiotic pipeline.

For ordinary people, this means better tools and stronger protection systems. For researchers and policy makers, that means collaborating in new ways.

The question now is not whether there are solutions to antibiotic resistance, but whether society will act fast enough to use them.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link