New supercomputer simulations show that if a million satellites were placed at different points between the Earth and the moon, fewer than 10% would survive long enough to make it worth the effort to send them out in the first place. While this is not as dire as it initially seemed, research shows that it does highlight the complex challenges of expanding humanity’s orbital capabilities.

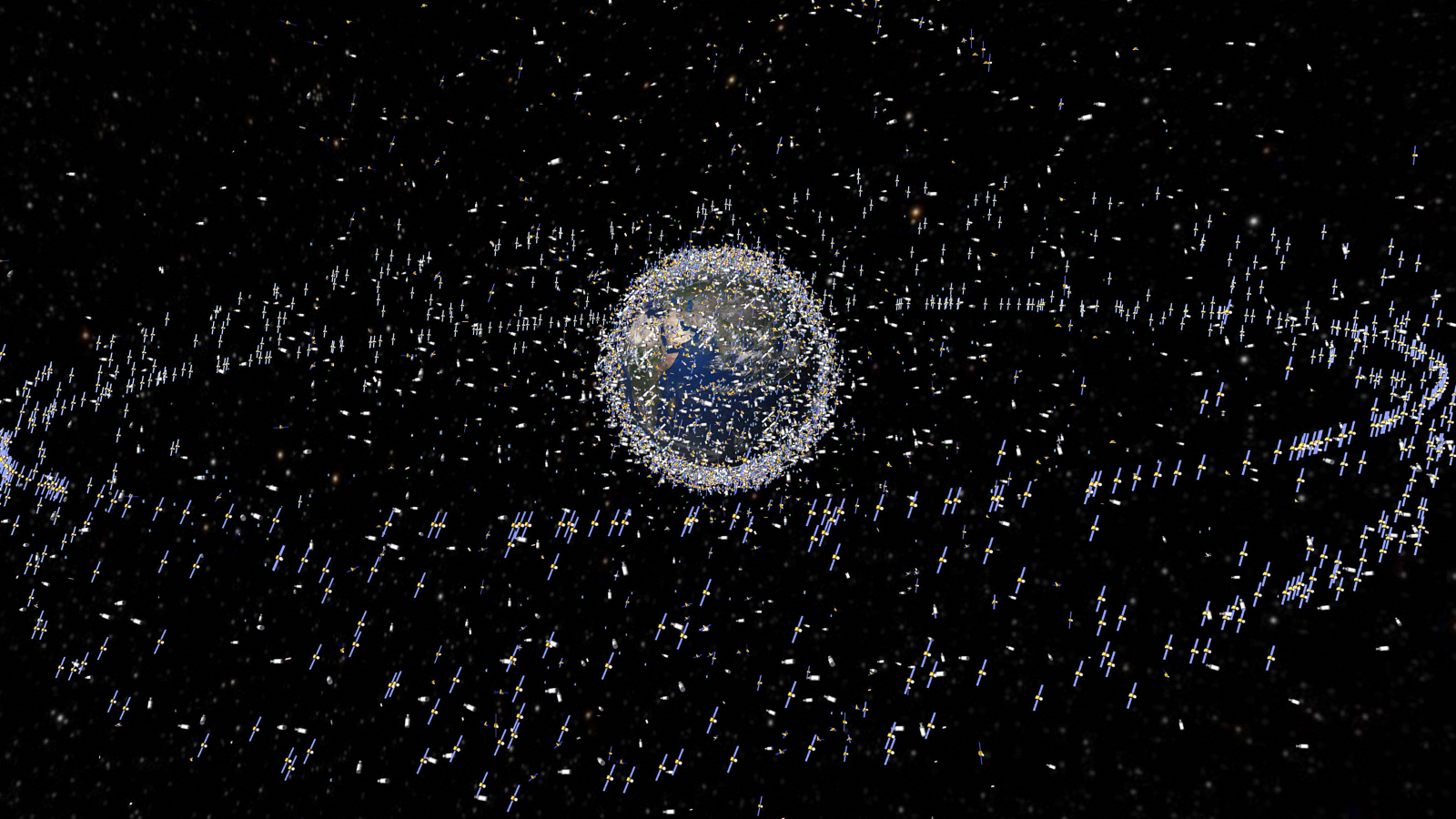

The number of active spacecraft orbiting Earth has skyrocketed in recent years, thanks in large part to the emergence of private satellite “megaconstellations” such as SpaceX’s infamous Starlink network and China’s growing Thousand Sails project, a trend that is only just beginning.

you may like

According to Live Science’s sister site Space.com, once LEO is fully saturated with spacecraft, the next logical step would be to start placing satellites in lunar space, the region between Earth and the moon. Doing so would not only benefit Earth’s infrastructure, but also provide internet and other services to future human colonies on the moon.

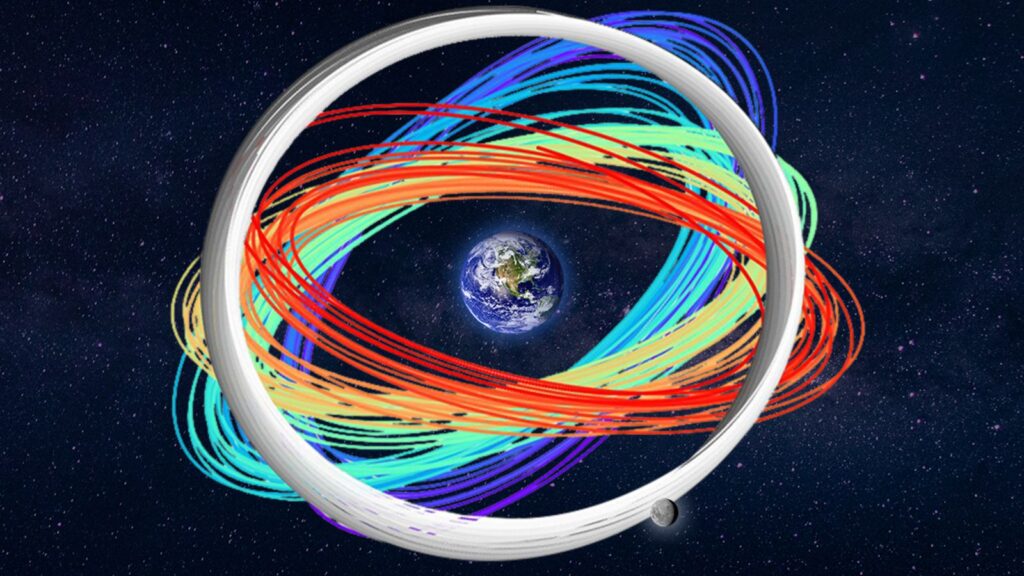

However, it is much more difficult to predict the trajectory of a spacecraft in cis-lunar space, as it is caught in a gravitational tug of war between the Earth, Moon, and Sun (which has major implications for celestial bodies far from Earth). Without Earth’s protective magnetic shield, radiation streaming from our home star could also destabilize the orbital trajectory of this region of space.

To solve this problem, researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California used two supercomputers (Quartz and Ruby) to simulate the orbits of about one million lunar objects. The simulation requires about 1.6 million CPU hours and takes about 182 years to complete on a single computer, according to a statement from LLNL. The supercomputer completed this task in just three days.

Approximately 54% of these simulated trajectories were stable for at least 1 year, but only 9.7% were stable throughout the 6 years of simulation. The orbital data was published in the AAS journal Research Notes in August 2025, and the team’s analysis was uploaded to the preprint server arXiv in December. (The second paper has not yet been peer-reviewed.)

The team designed the simulated trajectory to be as broad as possible, taking into account a variety of potential problems, including some that the team could not have foreseen.

“The point of this study was to make no assumptions about the type of trajectory we wanted,” study lead author Travis Yeager, a researcher at LLNL, said in a statement. “We tried to pretend we didn’t know anything about this space and went into it.”

uncertain trajectory

Unlike simulations of LEO orbits, which are more stable and repetitive, uncertainties are much higher in cis-lunar orbits. This means the team’s calculations have to “step forward in time in discrete chunks,” which is much more computationally intensive, the researchers wrote.

you may like

“If you want to know where it is, [cislunar] “The satellite will arrive within a week, but there’s no equation that actually tells us where it’s going to go. We have to move forward a little bit at a time,” Yeager said.

One of the most surprising factors influencing these orbits is the effect of Earth’s gravity, which changes subtly as the Earth rotates, the researchers noted. “Earth is not a point source of light,” Yeager said. “It’s actually floppy,” he added, because gravity is lower over Canada than over the Atlantic Ocean, for example.

Although the proportion of simulated satellites that survived is low, the results still represent approximately 97,000 stable orbits in lunar space and offer many possibilities for future exploration of this region. The researchers noted that knowing which trajectories didn’t work is just as valuable as knowing which trajectories did.

“From a data science perspective, this is an interesting dataset,” Jaeger said. “When you have a million orbits, you get a very rich analysis.”

The researchers shared the orbital trajectory on an open source platform, making the data freely accessible to anyone for future research on the Moon-Star satellites.

Source link