Scientific data on the atmospheric entry process of satellites is urgently needed to ensure a rapid, safe and sustainable disappearance of satellites at the end of their mission and to reduce risks on the ground and in space.

The European Space Agency (ESA) has now successfully piloted the remaining two cluster satellites, ensuring they will be able to record re-entry data from the plane as it returns to Earth orbit later this year.

“Moving two satellites to encounter a plane sounds extreme, but the unique reentry data we collect will be valuable in coordinating difficult encounters at large distances at sea,” explained ESA’s Space Debris Systems Engineer Béatrice Gillete.

Why atmospheric reentry data is urgently needed

Understanding how satellites fall through the atmosphere is critical to building safer, more sustainable spacecraft and reducing the risk of debris falling from space.

“Once we have precise data about when and how a satellite heats up, decomposes, and what materials survive, engineers can design satellites that burn out completely, so-called extinction-designed satellites,” said Stein Lemmens, ESA’s Draco project manager.

However, atmospheric entry is difficult to witness up close due to its violent nature and difficult-to-reach altitude of about 50 miles (80 km) above the Earth.

The frequency of re-entries is too high for balloon observations or satellite sample collection, and satellites in orbit are too far away to see much. The location of atmospheric reentry is usually too unpredictable to be observed from the ground or the air.

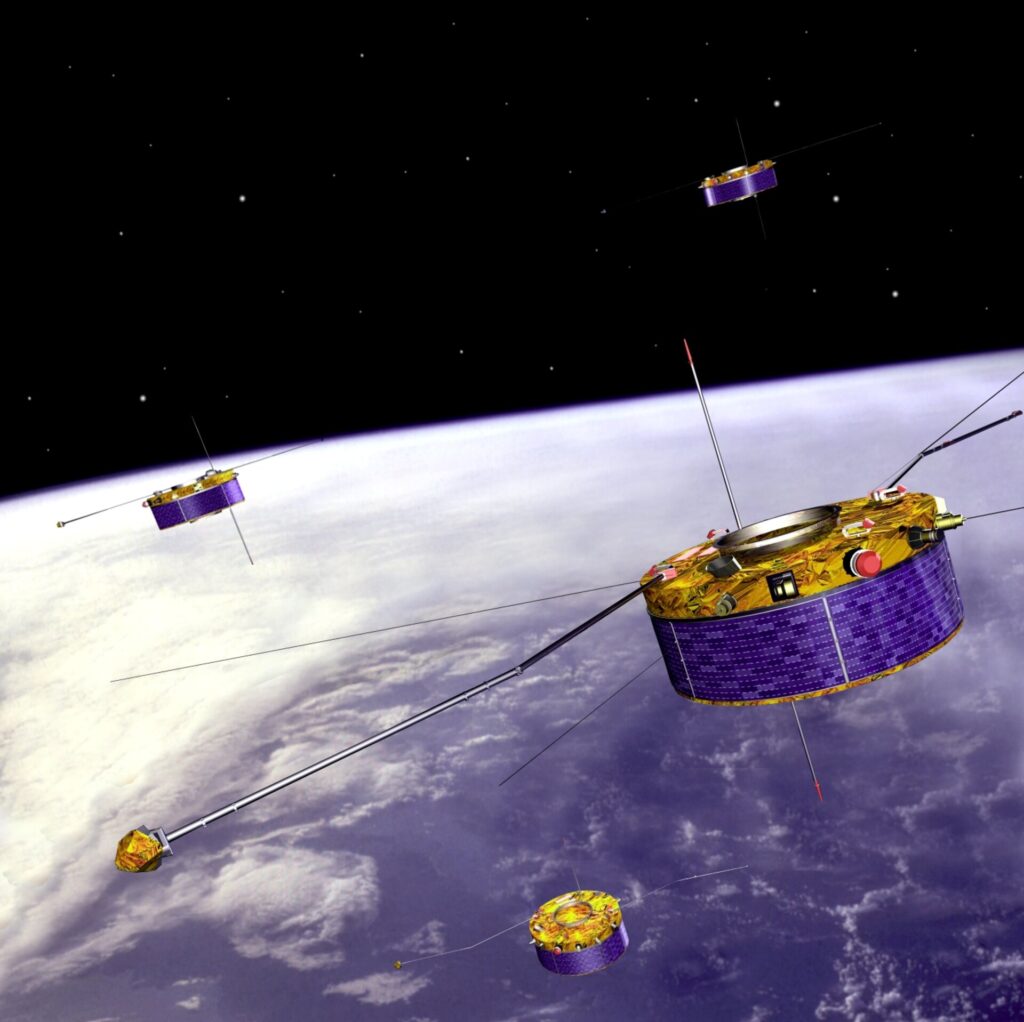

Cluster satellites offer an opportunity to address this challenge

With the Cluster Quartet’s “targeted reentry,” ESA is setting a precedent for a responsible approach to mitigating the growing problem of space debris and uncontrolled reentry from less commonly used orbits.

This shows that old missions can be disposed of in a safer and more sustainable way than was thought at the time of design.

“Because the four cluster satellites are identical, we have a unique opportunity to conduct valuable atmospheric reentry experiments to study satellite breakup by observing them reentering the atmosphere in predictable positions, with slightly different orbits, and under different weather conditions,” Gillete said.

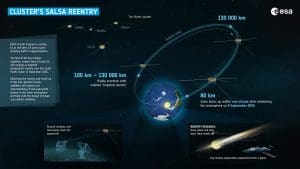

The first of the four clusters, Cluster 2, or Salsa, which reentered on September 8, 2024, was observed by scientists aboard the plane.

“Although predictions were slightly off, the atmospheric entry was captured by a variety of onboard instruments. It was a tense period until the sighting was finally confirmed,” Stigin said.

“Building on the lessons learned from Salsa, repeating this observational experiment two more times will add an additional dimension to the data, allowing us to make comparisons and establish patterns.”

Next step: Witness atmospheric reentry from inside

The next goal for ESA’s atmospheric reentry experts is for the Draco re-entry mission to witness the entire re-entry process from within, observing exactly when, how and what happens throughout the re-entry process.

Draco is scheduled to launch in 2027 and will undergo a violent reentry to record exactly what happened to the satellite.

With over 200 sensors, four cameras, and an indestructible capsule to securely store collected data, Draco provides a unique view inside destructive processes.

Stigin concludes: “We will use data from the cluster and Draco reentries to improve our reentry models.

“This will allow us to more accurately predict where objects will fall and their impact on the atmosphere, allowing us to build better satellites to further reduce the chance that debris will reach the ground and pose a risk to people and infrastructure.”

Source link