Discovered by astronomers, the worlds of up to 200 beyond our solar system are larger than estimates and can affect searches of extraterrestrial life.

It is the theory of a team of researchers who have seen hundreds of foreign ordinate planets, or skin-drain planets, observed by NASA’s transit exoplanet survey satellites (TESS).

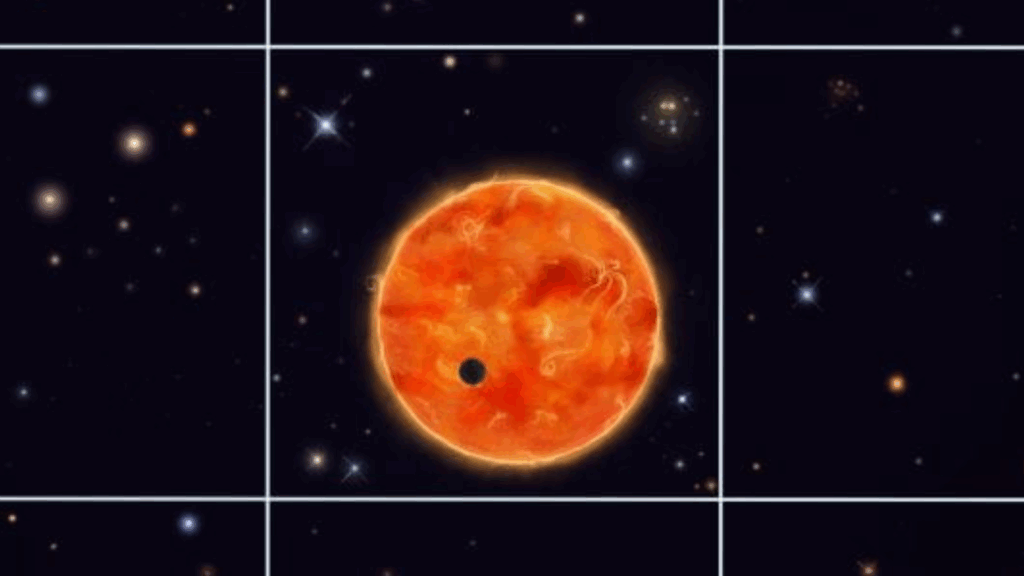

Tess hunts deplanets by catching them across the surface of their parent star or over a “transit,” and the light from that star causes small light. The research team discovered that light from the planet being transported can “contaminate” the “Tes” data, making it appear that the passing planets are blocking less light than they actually are. And it would make the planet look smaller than that.

You might like it

“We have discovered that hundreds of exoplanets are bigger than they appear. It shifts understanding of exoplanets on a large scale,” Te Han, a researcher and team leader at the University of California, Irvine University, said in a statement. “This means we may have actually found a planet like Earth that is far fewer than we thought.”

Delaminated planets throw shade

Exoplanets are so distant and faint that astronomers can image them directly on rare occasions.

In other words, transportation methods have become the most successful way to detect the world beyond the solar system. It requires that the planet and its stars be at the correct angle in relation to Earth, and astronomers must wait for the planet to make two passes to confirm its existence.

The transport method is perfect for finding short-period planets orbiting near host stars as it passes more frequently. This method also supports larger planets that block more light.

“We’re basically measuring the shadows of planets,” said team members and UC Irvine astronomer Paul Robertson.

Related: 12 Strange Reasons Humans Haven’t Find Alien Life Yet

The team observed hundreds of Tess’s observations of Tess in the explanets and sorted them by width of the exoplanet in question.

We then used data from the European Space Agency (ESA) star tracking mission Gaia to estimate how much Tess was experiencing during observation.

“Tess data is contaminated, and TE’s custom models are better than anyone else in the field,” Robertson said. “What we found in this study is that these planets could be systematically larger than we initially thought. That raises the question: How common are Earth-sized planets?”

Moving through Earth-like worlds: ocean planets could be more common

Due to the bias in the transport method described above, the number of exoplanets detected in Tess, which have similar size and composition to Earth, was already low.

“Of the single-planetary systems discovered by Tess, only three were thought to resemble Earth in their composition,” Han explained. “With these new discoveries, they’re all bigger than we thought.”

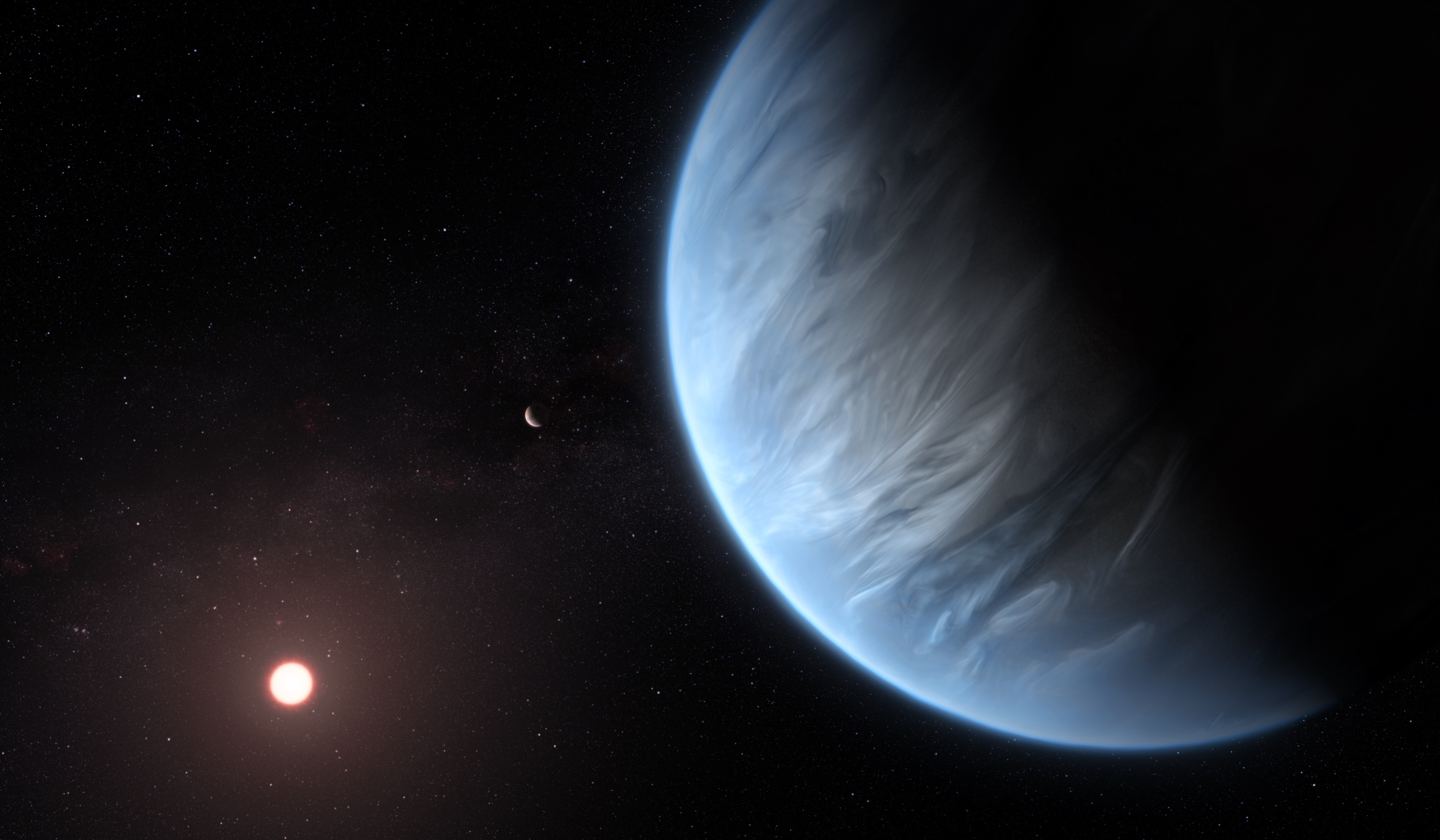

A possible outcome of this is that these explanets are large marine planets or “Hycean Worlds.” These worlds could be smaller gas giants than Jupiter, like Neptune and Uranus.

Hycean’s world is packed with water, but it can affect your search for life as it may be lacking other ingredients needed to produce life.

“This has important implications for understanding deplanets, including among other things, prioritizing James Webb’s Space Telescope tracking observations and the controversial presence of galaxy groups in the galaxy’s water world,” added Roberston.

The next step for Han, Roberston and colleagues is to revisit a planet that was previously thought to be uninhabited due to its size and see if it is larger than previously thought.

In the meantime, this study is a reminder of astronomers being cautious when evaluating TESS data.

The team’s investigation was published in the Astrophysics Journal Letter on July 14th.

This article was originally published on Space.com.

Source link