Fifty years after Phnom Penh fell into the Khmer Rouge rebels, the events of April 17, 1975 cast a long shadow over Cambodia and its political system.

Pol Pot’s radical peasant movement, emerging from the bloody and chaos of the spreading war in nearby Vietnam, defeated and defeated General Long Nol’s US-backed administration.

The war peaked on Thursday 50 years ago, when Pol Pot’s troops were wiped out into the Cambodian capital, ordering over two million people to the countryside.

With the abandonment of Cambodia’s urban centre, Khmer Rouge began rebuilding the country from “zero year” and transformed it into a society with no agricultural class.

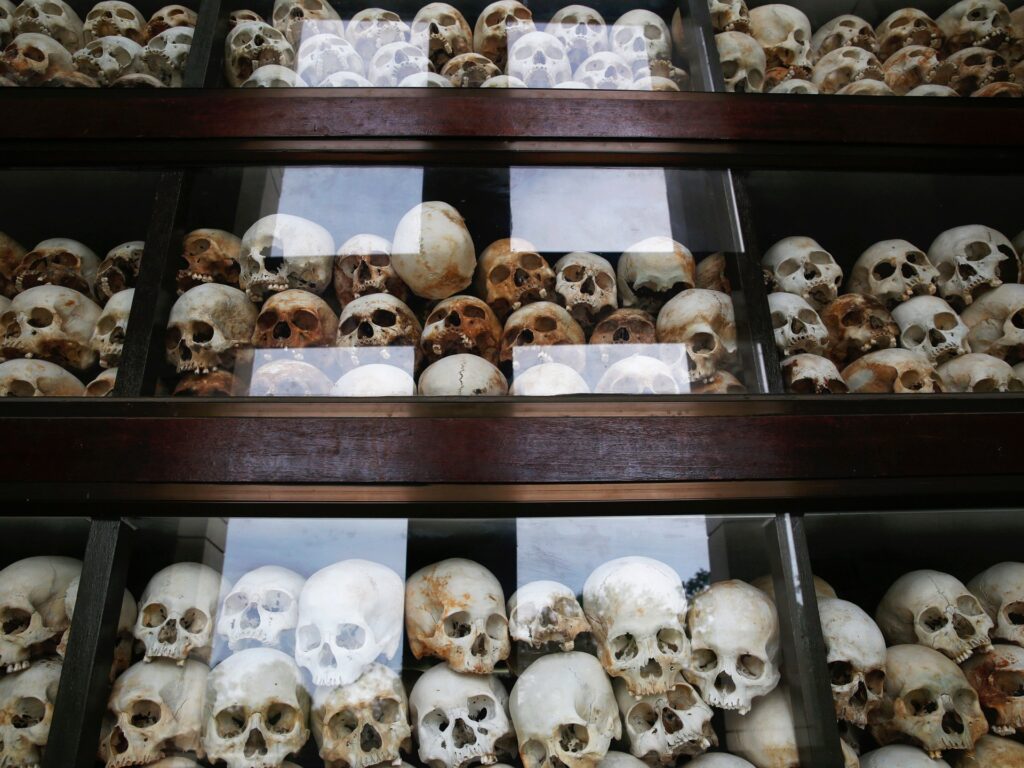

Under Polpot’s control, between 1.5 million and 3 million have died in less than four years. They will also almost wipe out Cambodia’s rich cultural history and religion.

Many Cambodians were brutally killed in the “murder field” of Khmer Rouge, but died much more in the labor of starvation, illness and fatigue on collective farms to build the rural utopia of the communist regime.

In late December 1978, Vietnam invaded with Cambodian exiles on January 7, 1979, defeating the Khmer Rouge from power. From this point on, general knowledge of Cambodia’s modern tragedy was picked up in the mid-2000s as it is usually a united war trimer, a united war trimer, a united war trimer.

But for many Cambodians, rather than being relegated to a history book, the collapse of Phnom Penh in 1975 and the fall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979 are embedded in the Cambodian political system.

According to analysts, the turbulent Khmer Rouge period has been still used since 1979 to justify the long-term rules (CPP) of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and personal rules for CPP leader Hunsen and his families since 1985. It was the senior senior leader of the CPP who worked with the Vietnamese army to drive out Pol Pot in 1979.

Although memories of those times have faded, in the late 1970s and decades, the CPP’s grip on power is as solid as ever.

“Creating a political system”

Aun Chhengpor, a policy researcher at Phnom Penh’s future forum think tank, said the ruling CPP “sees itself as a savior and a guardian of the nation.”

“It explains how we create a political system like it does today,” he said.

Most Cambodians embraced a system in which peace and stability were more important than anything else.

“There appears to be an unwritten social contract between the control facilities and the population, where as long as the CPP provides relative peace and a stable economy, the population will entrust governance and politics to the CPP,” Aun Chhengpor said.

“The big picture is how the CPP recognizes itself and its historical role in modern Cambodia. It’s not much different from the way the palace military facilities in Thailand and the Communist Party of Vietnam sees their role in their respective countries,” he said.

The CPP led Vietnam’s support regime for ten years from 1979 to 1989, reverting relative orders to Cambodia, even if the fighting continued in many parts of the country as Pol Pot fighters tried to re-lead control.

On the last day of the Cold War, Vietnam, economically and militarily exhausted, with economically and militarily exhausted, with Hun Sen, the leader of the country at the time, agreed to hold elections as part of a settlement to end its own civil war. From 1991 to 1993, Cambodia was managed by Cambodia’s United Nations Transition Authority (UNTAC).

Cambodia’s monarchy was formally reestablished, with elections held in 1993 for the first time in decades. The last Khmer Rouge soldiers, surrendering in 1999, symbolically closed one of the bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century.

Despite the rugged path to advance, Cambodia’s democracy had initial hope.

The Royal National Unification Battle for the Independent, Neutral, Peaceful and Cooperative Cambodia Party, well known for its acronym Funcinpec, won an unmanaged minor election in 1993.

The late King Norodom Sihanouk intervened to maintain a wealthy peace and mediate an agreement between the two sides that had a relatively successful election. The international community sighed for bailouts as Cambodia’s UNTAC mission was at the time the largest and most costly for a global organization, and UN member states were eager to declare investment in a country that would restructure its success.

A volatile alliance of former enemies who jointly ruled under the Power Shearing Agreement with the CPP and Funcinpec’s joint Prime Ministers and served for four years until it ended in a swift, bloody coup by Hun Sen in 1997.

Mu Sok-a, the ousted opposition leader who now leads the non-profit Khmer movement for the non-profit Khmer movement, told Al Jazeera that the CPP’s resistance to the 1993 democratic power transfer continues to echo throughout Cambodia today.

“The failed transfer of power in 1993 and the deals the then king made were bad. And the UN wanted to close the store, so the UN went together,” she told Al Jazeera from the US, who lives in exile after fleeing the intense authoritarianism of the CPP.

“The transition period, the transfer of power… that was the will of the people, but it never happened,” Mu Seok-a said.

The end of war does not mean the beginning of peace

After the 1997 coup, the CPP was not nearing losing power again until 2013, when challenged by the widely popular Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP).

By the time of the next general election in 2018, the CNRP had been banned from politics by the less independent courts of the state, and many of the opposition leaders were forced to flee the country or placed in prison for politically motivated charges.

Unhindered by viable political challengers, Hun Sen’s CPP won all seats in the 2018 national election, followed by all but five of the 125 parliamentary seats contested in the last general election in 2023.

The CPP was also firmly in line with China, with the once vibrant freedom press shut down and civil society organisations silenced.

After 38 years of power, Hun Sen left the sidelines as prime minister in 2023 for his son Hun Mane.

However, new challenges are emerging with Cambodia’s relative prosperity over the postwar decades, enormous inequality, and the rules of a de facto one-party.

Cambodia’s booming microcredit industry was meant to help drive Cambodians out of poverty, but the industry instead places a burden on families with high levels of personal debt. According to World Bank estimates, the population is only 17.4 million and gross domestic product (GDP) is estimated to have been placed in a $42 billion country in 2023 at over $16 billion.

Aun Chhengpor told Al Jazeera there are indications that the government is paying attention to these new issues and demographic changes.

Hun Mane’s cabinets are shifting towards “performance-based legitimacy” because they lack the “political capital” once given to the people who liberated the country from the Khmer Rouge.

“There is a percentage of the population that remembers Khmer Rouge, or available memories for that period, but shrinks each year,” said Sebastian Stringio, Cambodia author of Hunsen.

“I’m not thinking about it [the CPP ‘s legacy] It’s enough for most of the population born since the end of the Cold War,” Stringio told Al Jazeera.

Nowadays, analyst Annast Chenpo seems to even seem to have a limited amount of popular opposition now.

In January, Cambodian farmers blocked major highways to protest low prices of goods and suggested that there might be “some space” in the political system to challenge the local community-based issues, he said.

“[It] According to Aun Chhengpor, it will be a difficult struggle for broken political opposition to thrive, not to mention the hope of organizing among themselves and winning the general election.

“However, there are indications that the CPP still believes in one way or another that it limits democracy in terms of multi-party systems and how much democracy the democracy is saying when and how much,” he added.

Speaking during his exile from the US, Mu Sok-a saw the situation in Cambodia in a dimly darker way.

In the same month as Farmer’s protests in Cambodia, a former Cambodian parliament was shot dead in the daytime on the streets of Bangkok, Thailand’s capital.

The brave assassination of Lim Kimia, 74, a double Cambodian and French citizen, recalls memories of the chaotic political violence in Cambodia from the 1990s to the early 2000s.

According to Sochua, peace and stability exist only on the surface of Cambodia, where the water still runs deep.

“If there’s no space for politics and people to engage in politics, it’s not peace that prevails,” she said.

“It’s still a sense of war, anxiety and lack of freedom,” she told Al Jazeera.

“There will be no bloodshed at least 50 years after the war, but that alone does not mean there is peace.”

Source link