simple facts

Milestone: Experiments show that mutations occur spontaneously

Date: November 20, 1943

Location: Indiana University in Bloomington and Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee

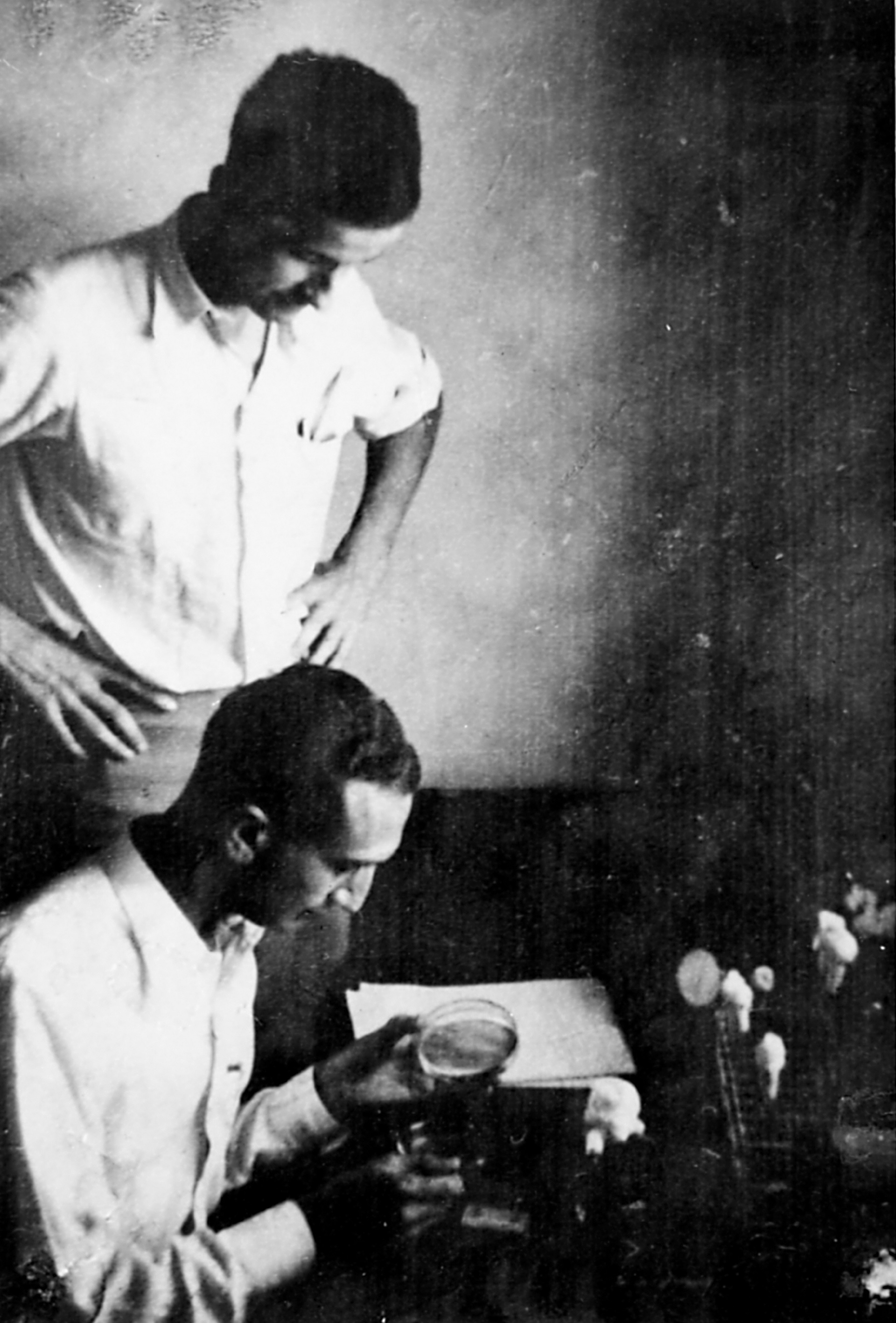

People: Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria

In 1943, physicists and biologists published a paper confirming one of the central pillars of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

The paper, by Max Delbrück of Vanderbilt University and Salvador Luria of Indiana University, describes a simple experiment called the “fluctuation test” that showed that mutations arose spontaneously in bacteria, rather than appearing in response to “selection pressure.”

This issue has been debated since Darwin published his classic On the Origin of Species in 1859. Darwin proposed that natural fluctuations occur randomly in all living things, and that environmental pressures make some of those fluctuations better or worse in a particular organism’s “struggle for survival.” Over time, these traits become more common as the fittest organisms survive and multiply. In contrast, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed in the early 1800s that fluctuations could be caused by environmental pressures.

you may like

When Delbrück and Luria conducted their experiments, Darwin’s theory was considered correct for plants and animals, but some scientists believed that the interaction between bacteriophages (viruses that attack bacteria) and their bacterial hosts could somehow induce resistance to the phages in bacteria.

Delbrück entered the field by chance. The disgruntled physicist moved from Germany to the United States due to hostility from the Nazi regime and became interested in the idea of modeling genetics using ideas from quantum mechanics and atomic theory.

While working in California, he met researchers who were studying a newly characterized bacterium called E. coli that had been cultured from Los Angeles sewage. Researchers have identified a phage that preys on E. coli. Delbrück was struck by how easy it was to identify and count individual phage particles under a microscope.

“If you put them on a plate full of bacteria, by the next morning every virus particle will have eaten macroscopically 1 mm.” [0.04 inch] Delbrück said in an oral history recorded in the 1970s. “This seemed far beyond my wildest dreams of doing simple experiments on things like atoms in biology.”

In December 1940, Delbrück met Luria, an Italian-Jewish doctor, at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. Like Delbrück, Luria was on the run from the Nazis, and like Delbrück, she was bored with her chosen profession.

Luria had seen some of the early research on phages and was also fascinated by the idea of using phages to study genes as if they were collections of atoms. At that time, people understood the concept of genes, but they had little understanding of what they were made of.

About nine months after they met, the two decided to test whether phages could induce resistance in E. coli. They were at a loss as to how to proceed until Luria chatted with a colleague who was playing slots. He realized that statistics could be used to distinguish between random and phage-induced mutations, that is, to determine the direction of cause and effect.

you may like

They filled large numbers of tubes with E. coli, exposed the bacteria to phages, and cultured them continuously on plates. They reasoned that if mutations were acquired, E. coli with resistance mutations would occur at approximately the same rate on all plates only after the phages were introduced into the plates. In contrast, if mutations occurred randomly, there would be even greater variation in the number of resistant bacteria among cultures. Some will become “jackpot plates” containing more resistant E. coli. That’s because E. coli happened to evolve the resistance gene early in the culture’s growth, rather than later.

This became known as the “variation test,” and in 1943 the pair published research confirming that mutations occur randomly within bacteria.

That same year, they began collaborating with microbial chemist Alfred Hershey, then at Washington University in St. Louis. The trio also showed that phages contain multiple genes and that viruses can exchange genetic information with each other within the same bacterium, a process known as genetic recombination. Hershey and co-researcher Martha Chase then showed that DNA is the carrier of that genetic information. Hershey, Luria, and Delbrück were awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contributions to genetics.

Interestingly, while their study solidified Darwin’s hypothesis that natural selection operates on the basis of random variation, some new research suggests that not all mutations are completely random. The mutation rate of “essential genes” is lower than that of more incidental genes, at least in certain plants. And recent research suggests that if the team had chosen a different bacterial-phage system to study, such as one that uses the bacterial immune system CRISPR to fight off phages, the statistical results would not have been as clear-cut.

Source link