simple facts

Milestone: First SARS infection

Date: November 16, 2002

Location: Foshan, China

Person: Food handler

In January 2003, Chinese epidemiologists identified two cases of “atypical pneumonia” in patients who visited health care workers in Guangdong province. The team began contact tracing and eventually discovered that the disease-causing bacteria had been circulating since November 16, 2002, when the patient became ill.

The earliest cases in November were “food handlers,” people who worked as chefs in restaurants or as vendors at “wet markets,” where live animals such as poultry and more exotic animals such as civets and raccoon dogs were displayed in crowded conditions.

By the time disease researchers in China realized there might be an outbreak, the disease had already been circulating for two months and had spread to health care workers.

you may like

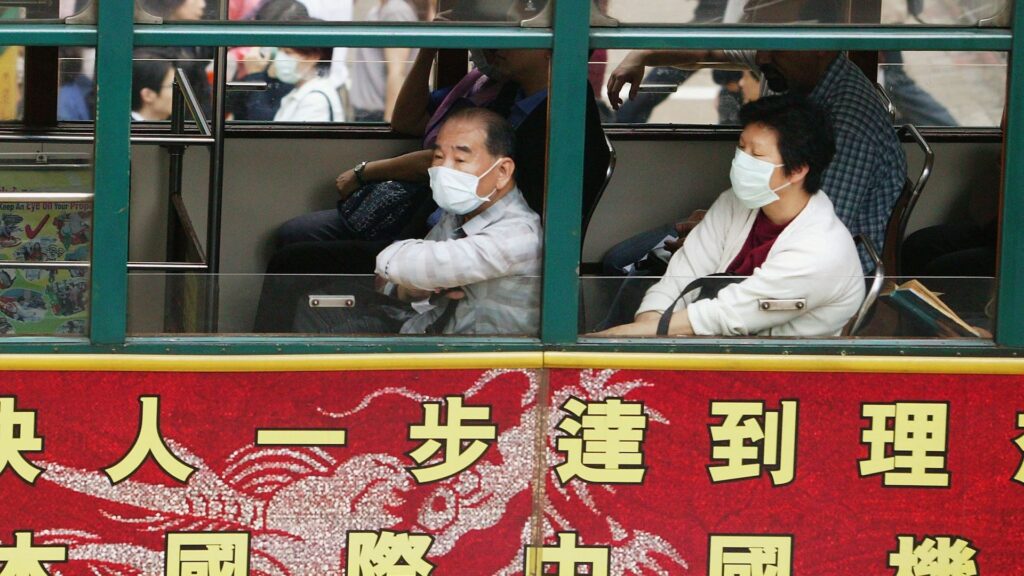

The disease arrived in Hong Kong in February and exploded on February 21, 2003, when a nephrologist from southern China visited the region for a wedding. He became ill during the trip and later died from the disease.

In March, World Health Organization (WHO) case investigator Dr. Carlo Urbani came to investigate a case observed in a businessman who had traveled to Hong Kong and was hospitalized there before arriving in Hanoi, Vietnam. Urbani eventually contracted the disease himself and died that same month.

By March 12, the WHO had issued a warning about a severe pneumonia of unknown origin that was occurring in people in China, Hong Kong, and Vietnam. By March 15th, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had officially named the disease Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and by March 24th, it had identified the cause as a novel coronavirus.

By that time, the epidemic was nearing its peak. The pandemic lasted several months, spreading to 28 countries outside China, with 29 cases in the United States, affecting more than 8,000 people, and 774 of them died. The mortality rate of this disease is estimated to be approximately 9.6%.

In early 2004, there was a brief resurgence of SARS, but aggressive and rapid contact tracing and containment strategies quickly brought the spread under control.

This second flare-up allowed scientists to trace the source of the SARS virus to civets and raccoon dogs sold on the market. The following year, scientists claimed that the yellow-bellied bat was the pathogen’s natural animal host, but it wasn’t until 2017 that researchers found conclusive evidence. Bats are rich in a virus similar to SARS and live in remote caves in China’s Yunnan province. The cave was located only a mile away from the village.

“There is a potential risk of human contagion and the emergence of a SARS-like disease,” the authors warned in a paper at the time.

you may like

The SARS outbreak, while scary at the time, was ultimately just a dry run for the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which swept the world from March 2020 to May 2023 after the initial cases began appearing in November 2019. The two viruses belong to the same general coronavirus family and likely originated from similar animal hosts.

Scientists and public health officials have successfully applied some of the lessons from SARS to the coronavirus pandemic. For example, when SARS first emerged, China had a very rudimentary infectious disease surveillance system. Although it reported cases of infectious diseases and food poisoning, communication was done by telephone and there was no standardized case reporting system, nor was there a system for contact tracing or collecting test results. After the SARS outbreak, China quickly introduced a thorough contact tracing and disease surveillance system.

That would prove crucial when SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, emerges in China. Hundreds of thousands of cases were recorded in China during the first wave, which ended in China by mid-February. It comes just months after investigators first reported a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown cause in Wuhan. (Strict lockdowns also likely helped limit the spread of the virus in the country.)

While it took months to identify the cause of the SARS pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was identified less than two weeks after the first confirmed case. And although there was no specific treatment for SARS, by mid-March 2020, thanks to mRNA technology that had been in development for decades, a vaccine against the newly identified virus was entering clinical trials.

Other lessons the world learned from SARS were only partially learned. When the source of SARS was identified in 2017, Dr. Kwok-Yong Yuen, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong who co-discovered the virus, told Nature News that the discovery “reinforces the idea that we should not disturb the habitat of wild animals and that we should never put wild animals on the market.” He told Nature News that respecting nature is “the way to stay away from the harm of new infectious diseases.” Still, the practice continued.

In some ways, the SARS epidemic lulled public health agencies into a false sense of security. SARS and related coronavirus infections, such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), were much more deadly than SARS-CoV-2, but much easier to contain. The outbreak was relatively easy to control using contact tracing and other public health measures, rather than requiring vaccine distribution.

That’s because the infectious period of SARS was shorter than that of the new coronavirus. While SARS-CoV-2 is easily transmitted during the early stages of illness, sometimes even before symptoms appear, SARS-CoV-2 was most contagious during the second week of severe illness.

Source link