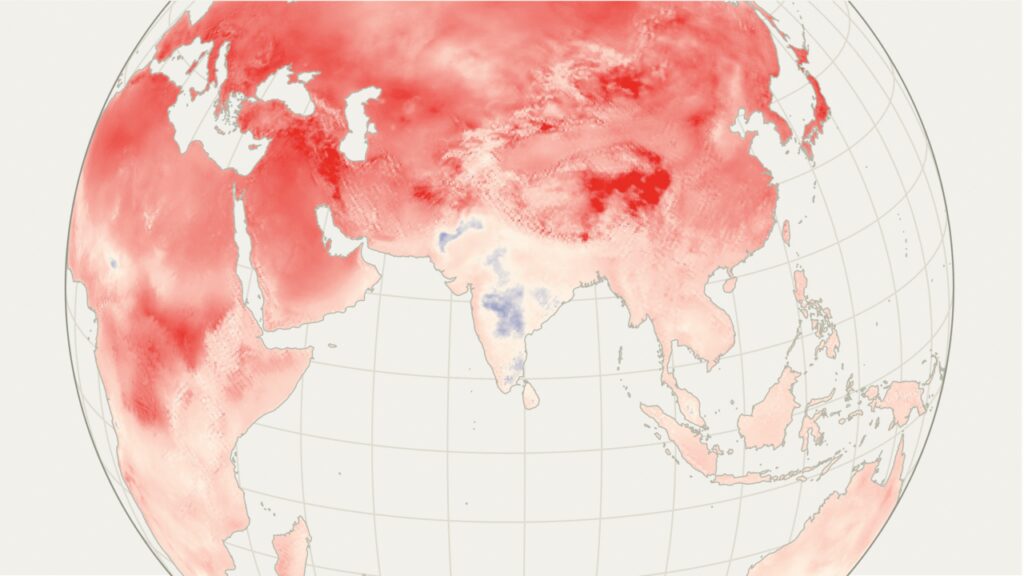

Changes in average temperature, 1980-84 to 2020-24

coolerwarmer

Climate change is a global phenomenon, but temperatures around the world have not risen uniformly.

The poles and high latitudes warmed faster than near the equator.

Still, one region stands out as an abnormality: South Asia.

oOver the past 40 years, South Asia has warmed much more slowly than elsewhere in the world. Temperatures in this region increased at about 0.09°C per decade. Scientists are not yet convinced how to explain the “warming holes” in South Asia, but there is strong evidence that both smog and irrigation changes play a key role. If so, that changes when pollution fades and irrigation spread slows. Dirty Air kills millions of people in the area each year. It’s essential to clean it. But that cleanup can cause a dangerous surge in global warming.

South Asia is already a hot place. The times before the monsoon from April to June are usually the worst. In these months, temperatures in the Indian Gangatic Plain (a region spreading in eastern North India, north India and Bangladesh) can regularly exceed 40. This is a measure that includes the extent to which humidity makes high temperatures even more dangerous for more than 40% of people experiencing extremely strong or extreme heat stress each year. High levels of heat stress are fatal, especially for elderly people and those with health problems.

Average level population

Daily heat stress, 2020-24 years

India, Pakistan

and Bangladesh

Maximum “feel-like” temperature*, ºC

*Scale explaining universal thermal climate index, temperature, wind, humidity and radiation

Average level population

Daily heat stress, 2020-24 years

India,

Pakistan&

Bangladesh

Maximum “feel-like” temperature*, ºC

*Universal Heat Climate Index, its scale

Explains temperature, wind, humidity, and radiation

Average level population

Daily heat stress, 2020-24 years

India,

Pakistan&

Bangladesh

Maximum “feel-like” temperature*, ºC

*Universal Heat Climate Index, its scale

Explains temperature, wind, humidity, and radiation

Such dangerous hot days are becoming more frequent. Already this year, mercury has reached 44°C in some parts of India. However, despite rising temperatures, South Asia is avoiding taking the full brunt of global warming. One explanation is high levels of pollution in the area. Long-lived greenhouse gases that cause global warming are widely distributed all over the world. Other types of pollution are more regional and regional. And much of this localized contamination cools the surface rather than warming it.

Changes in average temperature, 1980-84 to 2020-24

coolerwarmer

The Indian air is particularly bad at the foot of the Himalayas, where the mountains prevent air from circulating. Seaside locations such as Mumbai enjoy better air quality.

The Indian Gangic Plain is one of the most polluted regions in the world. Heavy industry, traffic emissions, burning agricultural waste, and using solid fuels for cooking all contribute to high aerosol levels. Several studies suggest that higher levels of these contaminants over the past 20 years may have somewhat negated the effects of temperature rises in the region. However, rather than reflecting it, the soot particles absorb sunlight and cool the surface, but the fact that they warm the atmosphere complicates the problem. One recent study found that in the spring of 2020, when lockdowns in many Indian cities caused a dramatic decline in pollutants, temperatures spiked as some scientists had expected, but rather unusually cool. The paper examined temperatures alone for months, so the changes could be due to accidental fluctuations, but “it’s still a bit puzzling,” says Loretta Mickley, a climate scientist at Harvard University.

The expansion of irrigation is another explanation of a place that is slower than in the Ers era in South Asia. As water evaporates, it absorbs heat and cools the air around it. In India, the irrigated region has doubled since 1980. Scientists believe the cooling effects of expanding irrigation in the region may mask the effects of global warming. One study published in Nature Communications in 2020 estimates that without irrigation, South Asia will be twice to eight times as extreme heat as it is now.

Changes in average temperature, 1980-84 to 2020-24

coolerwarmer

Scientists believe that rapid growth in irrigated areas across India could be one of the reasons why it has become slower and warmer than elsewhere at similar latitudes.

There is no scientific consensus yet about how slow these factors slow global warming in South Asia. Scientists need to better understand the complexity of how pollution and irrigation affect local temperatures, rainfall and monsoon timing, and how all these factors interact. However, experts agree on what’s going forward. In a recent meeting with Indian and American scientists in Delhi, University of Washington air scientist David Battisti said that over the next 20 years, India is “almost certain” to warm up twice as fast as the last 20 years.

In the next few decades, neither pollution nor irrigation will continue to grow over the past 40 years. Both hide additional warming as long as the levels are rising. If pollution and irrigation are stable, South Asia will feel the full impact of new global warming. As they decrease, the region senses the effects of temperature rises from the past decades when these factors were masked.

And reduce the number of them doing so. “The truth is that India cannot continue irrigation,” says Dr. Shragh. The area’s groundwater levels are depleted. “And they can’t continue to hold on to the level of air pollution they have.” Pollution efforts are the flagship program of the government of India. By 2024, the country was aiming to reduce particulate matter by 20-30% compared to 2017. So far, the main achievement of the project is to build an aerosol monitoring station in a location that we didn’t have before. Many cities missed their 2024 targets, but a survey released earlier this year found that pollution levels have improved somewhat over the past decade.

Other countries show that it can be done. In the 1960s, Japan was one of the most polluted places in the world. Throughout the next 20 years, the country has enacted new laws to reduce pollution and introduced environmental taxes and fees for waste. By the 1980s, aerosol levels had dropped dramatically. Recently, China has reduced aerosol emissions.

Currently, air pollution is much more blight for South Asia than extreme heat. According to the global burden of disease research, in 2021, aerosol contamination killed between 2M and 3M people in the region, with extreme fever causing 100,000 to 600,000 deaths. Bhargav Krishna of Sustainable Futures Collaborative, a research institute in Delhi, said: “It’s simply because of the scale of exposure people have to deal with and the exposure throughout the year.”

South Asia, estimated deaths due to environmental risk factors, 2021

Unsafe water, sanitation

and hand wash

Other environments

risk

South Asia, presumed deaths

Environmental risk factors, 2021

Unsafe water,

Hygiene and

Hand wash

Other environments

risk

South Asia, presumed death

Due to environmental risk factors, 2021

Unsafe water, sanitation

and hand wash

Other environments

risk

Even a small rise in temperature in South Asia can be devastating. Already, the effects of heat and humidity are on the day when the effects of heat and humidity push each other over areas close to the limits of human habitability (almost equivalent to a temperature of 45°C with 50% relative humidity). These conditions are expected to be much more common. By 2047, the average Indian might experience heat stress four times more days, according to Dr. Battisti. The assumptions of pollution and irrigation levels are stable. Drop both sets and the numbers get even bigger.

For many people in South Asia, the heat is inevitable. According to a 2022 Hindustan Times analysis, about half of Indians work outdoors, with only 10% of households in the country air conditioning. Many Indian cities have adopted heatwave action plans, laying out ways to provide people with cooling and water in extreme heat. However, few people take steps to make cities more resilient or reduce heat exposure. Without dramatic changes, future temperature surges will be fatal. ■

Source: Copernicus; Aaron Van Donkelaar et al. Author: 2023. Yulian Gao et al. Author: 2024. economist

Source link