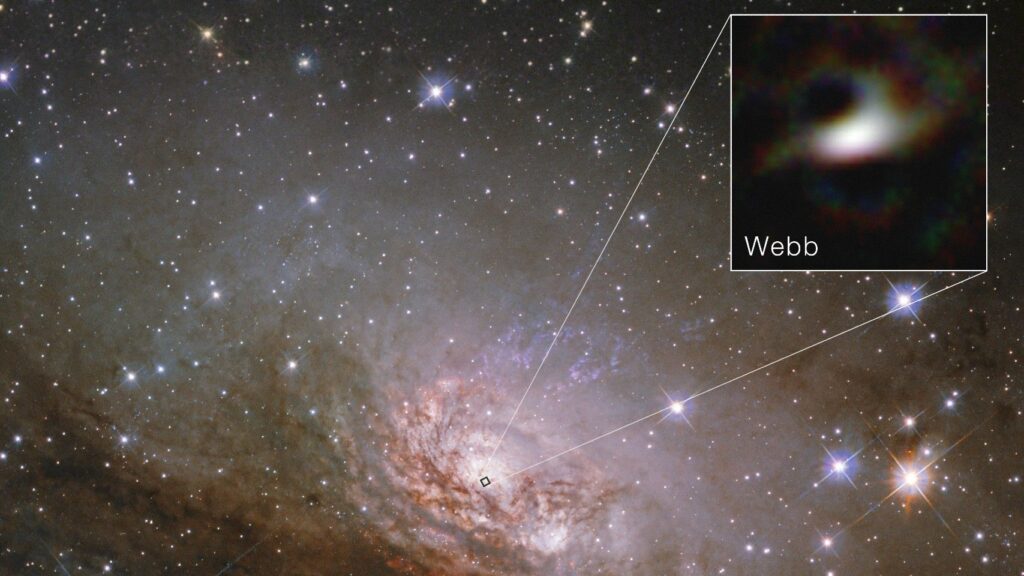

Astronomers have revealed the clearest images yet of the area around a black hole from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). This spectacular view could help solve a decades-old mystery, overturning long-held beliefs about the universe’s most extreme objects.

Since the 1990s, astronomers have observed interesting brightness in infrared wavelengths around active supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the centers of several galaxies. Previously, they thought these excess infrared emissions were due to outflows, streams of superheated material spewed out of the black hole.

you may like

Combining data from JWST with numerous ground-based observations, it becomes clear that the excess infrared radiation comes from a disk of dusty material falling into the SMBH, the center of the Circinus galaxy, rather than from material flowing out of it.

This galactic revelation could help astronomers better understand the growth and evolution of SMBHs and the impact these giant dark monsters have on their host galaxies.

donut and disc

Active black holes, such as those at the center of galaxies, are fed by huge rings of raining down gas and dust. As the black hole draws material from the inner walls of this “doughnut” known as the torus, the material forms a thinner accretion disk, and water spirals into the drain into the black hole.

The tidal forces of a black hole accelerate falling matter to high speeds. The friction created within the disk causes the swirling material to emit a light that shines so brightly that it obscures astronomers’ view of the interior region around the black hole.

However, black holes are not vacuum cleaners, and black holes also have feeding restrictions. There they blow some of the swirling material into space in the form of jets or “winds.” Understanding the nature of a black hole’s torus, accretion disk, and outflow is therefore key to understanding how black holes of different sizes accrete and eject material, potentially forming host galaxies by suppressing or enhancing star formation across the galactic scale.

A long-standing mystery is solved

Circinus’ dense gas and bright starlight have previously prevented astronomers from observing the galaxy’s central region and SMBH in detail.

“To study supermassive black holes, despite our inability to understand them, we needed to obtain the total intensity of the interior regions of galaxies over a wide range of wavelengths and feed that data into our models,” study lead author Enrique López Rodríguez, a galaxy evolution researcher at the University of South Carolina, said in a NASA statement.

you may like

Previous models fit the observed spectra of the torus, accretion disk, and outflow separately, but were unable to resolve the entire region. As a result, astronomers could not explain which part of the SMBH’s surroundings was causing the excess infrared radiation.

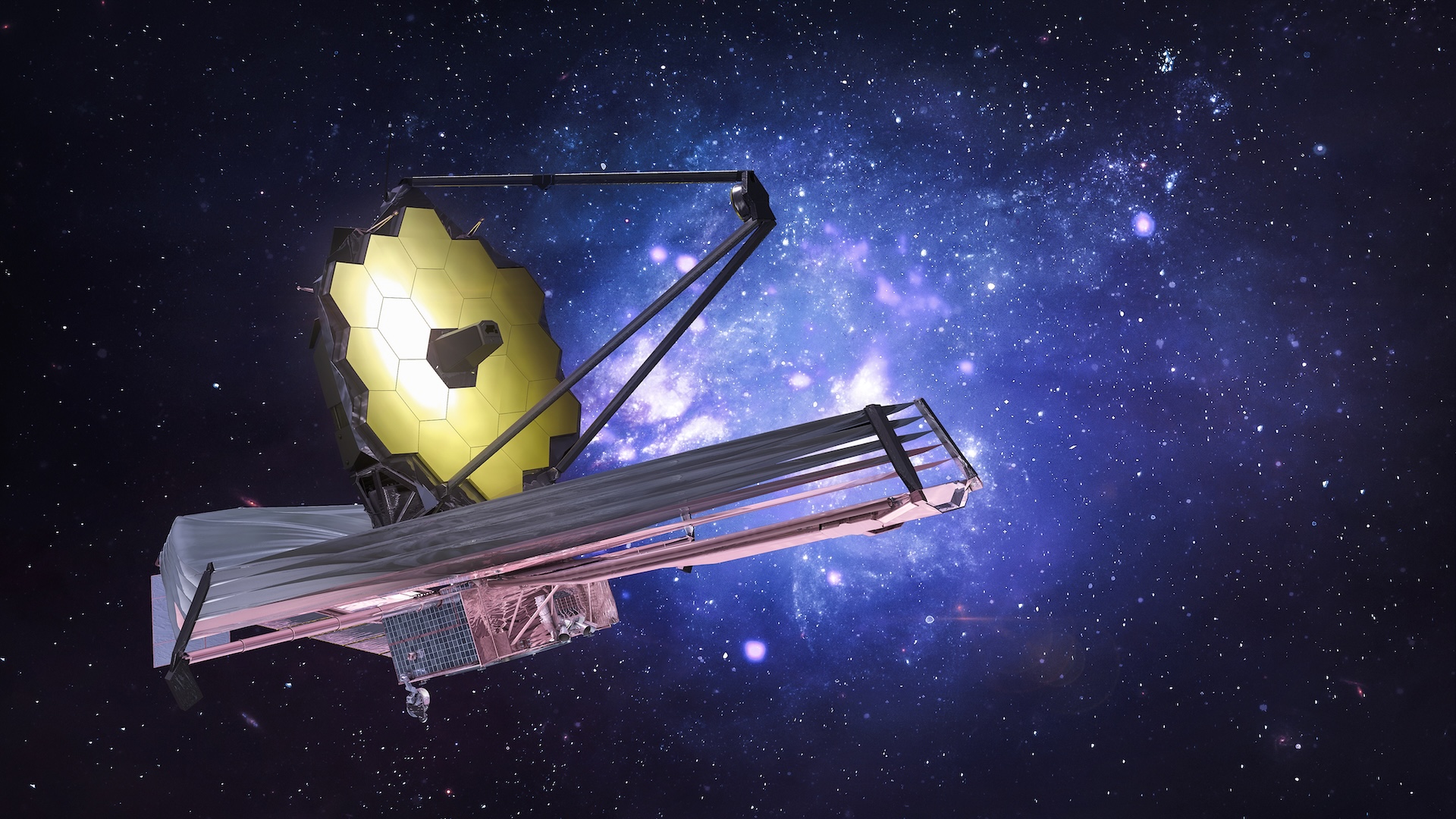

JWST’s advanced capabilities allow astronomers to peer through Circinus’ dust and starlight, giving them a clearer picture of SMBH’s environment. To do this, they used an imaging technique known as interferometry.

Ground-based interferometry typically requires a series of telescopes or mirrors working together to collect and combine light from celestial objects over a large area. In this method, light from multiple sources is combined, and the electromagnetic waves that make up that light create interference patterns that astronomers can analyze to reveal the size, shape, and other properties of those objects.

However, unlike these ground-based facilities, the space-based JWST can operate as its own interferometer array through the Aperture Masking Interferometer (AMI), a component of the telescope’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrometer (NIRISS) instrument. Similar to a camera aperture, the AMI is an opaque physical mask with seven small hexagonal holes that control the amount and direction of light entering JWST’s detectors.

Overall, AMI effectively doubles the resolution of JWST. “This allows us to see images twice as clearly,” Joel Sánchez Bermudez, an astrophysicist at the National University of Mexico and co-author of the study, said in a statement. “Instead of Webb’s 6.5 meters.” [21 feet] Because of its large diameter, it’s like observing this area with a 13-meter space telescope. ”

By doubling its resolution, JWST provided the clearest image yet of the 33-light-year-wide region at the center of Circinus. This unprecedented image allowed the researchers to calculate that most of the excess infrared radiation (about 87%) comes from the dusty disk actively feeding the central black hole. “It’s the inside of a donut hole,” López-Rodriguez said in an email. Previous studies had suggested that the excess could come from hot dusty winds or the galaxy’s remaining starlight, but the researchers found that less than 1% of these emissions were due to energy spills flowing out of the SMBH.

López-Rodriguez said this accretion may have eliminated star formation in the center of Circinus, but other types of JWST-based observations will be needed to confirm this.

valuable perspective

In addition to revealing previously hidden SMBH mechanisms, this study highlights the potential of JWST-based interferometry to study a variety of astronomical objects, including other active SMBHs at the centers of nearby galaxies. By increasing the sample size, astronomers hope to determine whether the infrared radiation from other SMBHs is due to dusty disks or hot outflows.

“To gain valuable JWST time, AMI must be used on targets that are impossible from the ground or at wavelengths that are blocked by Earth’s atmosphere,” study co-author Julien Girard, a senior scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, told Live Science in an email.

AMI-based observations can better illuminate our own solar system. They recently provided a detailed study of the volcanoes on Jupiter’s hellish moon Io, Girard added. As a result, AMI can observe a wide variety of space objects of all shapes and sizes, from lava-oozing satellites to dust-encrusted black holes. In the future, it could help astronomers detect moons around prominent asteroids or reveal the orbits and masses of multi-star systems, Girard added.

Source link