A groundbreaking improvement in Microsoft’s glass-based data storage technology allows ordinary glassware, such as those used in cookware and oven doors, to store terabytes of data, which is retained for 10,000 years.

The technology, which has been under development since 2019 under the name Project Silica, has been steadily improving, and scientists today published a summary of their latest innovations in the journal Nature.

In a new study, the researchers showed that they can encode data into ordinary borosilicate glass, a durable, heat-resistant type of glass commonly used in most kitchen glassware. Previously, scientists could only store data in pure fused silica glass, which was expensive to manufacture and limited in availability. They also demonstrated several new data encoding and data reading techniques.

you may like

“This advancement addresses a key barrier to commercialization: cost and availability of storage media,” study co-author Richard Black, partner research manager at Microsoft, said in a statement. “We have cracked the science of parallel high-speed writing and developed a technique that enables accelerated aging testing of written glass, which suggests that the data should remain intact for at least 10,000 years.”

The researchers pasted 4.8 TB of data (the equivalent of about 200 4K movies) onto 301 layers of 0.08 x 4.72 inches (2 x 120 millimeters) glass at a write speed of 3.13 megabytes per second (MB/s). Although this is much slower than the write speeds of hard drives (about 160 MB/s) and solid state drives (about 7,000 MB/s), scientists have found that data can be stored for more than 10,000 years. In contrast, most hard drives and solid state drives have a lifespan of up to about 10 years.

Its longevity and stability are central drivers for innovations like glass- and ceramic-based storage devices, primarily for archival reasons rather than for use in most everyday devices. In theory, these alternative storage formats are more reliable than existing formats and serve as long-term repositories for generated data.

To demonstrate this idea, Microsoft scientists previously outlined plans to store music in Norway’s Global Music Vault. The news also follows another independent breakthrough in DNA storage: 360 TB of data can be stored in 0.8 kilometers of DNA.

Focused on archival storage

In this study, scientists uncovered several discoveries that make writing and reading on glass more efficient and cost-effective.

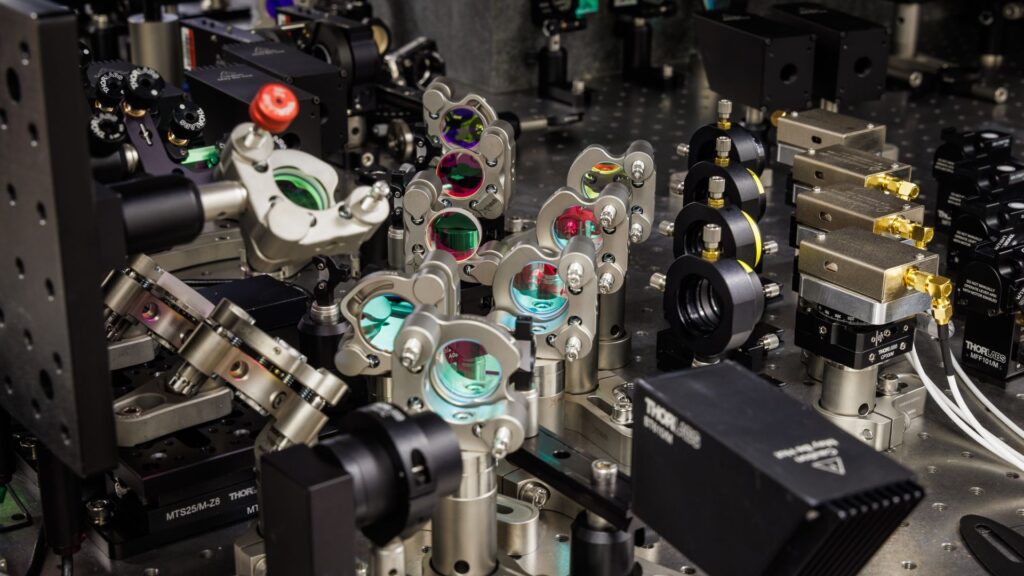

First, they detailed an advancement in a technique called birefringent voxel writing with laser pulses. Birefringence is the phenomenon of double refraction, and voxels are the 3D equivalent of 2D pixels. Scientists have developed a pseudo-single pulse that is an improvement on the previous two pulses. In this pulse, one pulse can be split after polarization to form the first pulse for one voxel and the second pulse for another voxel.

It has added a parallel write feature that allows many data voxels to be written in close proximity at the same time, significantly increasing write speeds.

The researchers also devised a new storage type in the form of “topological voxels.” This type allows data to be encoded in the phase changes in the glass (changes in the phase of the material due to changes in energy and pressure) rather than the polarization of the glass that occurs within the birefringent voxels. This is possible with just one pulse, and the scientists have also devised a new technique to read the data held in this way.

Finally, the team discovered a way to identify aged data stored in voxels within the glass. Using this method in conjunction with standard accelerated aging techniques, they found that the data could last for more than 10,000 years.

In the future, the team plans to look at ways to improve writing and reading techniques, including ways to enhance the lasers that write data to glass storage devices. We also plan to explore different glass compositions to find the ideal material for storing data in this format.

Chen, F., Wu, B. (2026). Laser-written glass tablets can store data for thousands of years. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-026-00286-5

Source link