Francesco Cacciator is a self-proclaimed skeptic. But after spending 20 years in the European aerospace industry and struck a “crisis,” as he said, he made an undeniably optimistic bet. He started a space company.

“You ask yourself, ‘What am I doing?’,” he said in a recent interview. “I offered some interesting opportunities, but then I fell down and realized I wanted to make something myself.”

Something turns out to be one of the most challenging problems in aerospace: re-entry. Caxiatoll, along with co-founder Víctor Gómez García, founded Orbital Paradigm, a Madrid-based startup that will build a re-entry capsule to unlock new markets of materials created with zero gravity.

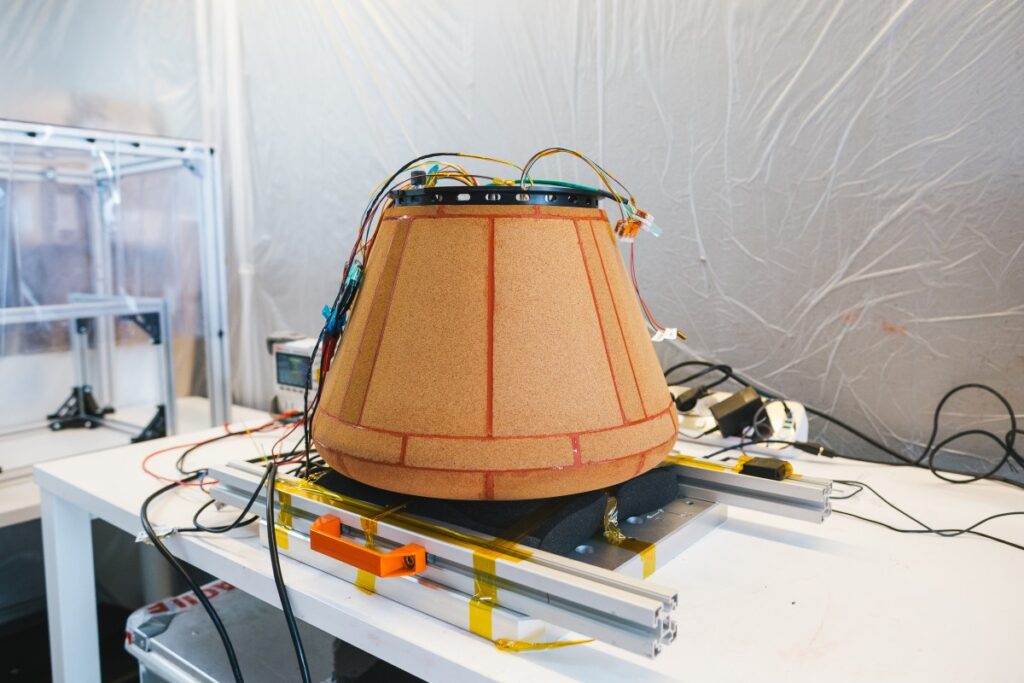

In less than two years, a team of nine members built a test capsule called Kid, the predecessor of the future reusable space capsule called Kestrel, for less than 1 million euros. Children are intentionally minimal. It weighs about 25 kilograms, is about 16 inches wide and has no propulsion. It is marked for the first time that a startup has put its hardware on orbit.

Customers for this first demonstration mission include French space robotics startup Alatyr, Leibniz University Hanover in Germany, and a third unnamed customer. So far, the company has raised 1.5 million euros of seed funding from ID4, Demium, Pinama, Evercurious and Akka.

The orbital paradigm did not begin to develop return capsules first. The co-founders initially envisioned robotics within the space, but prospects repeatedly said that what they really wanted was to go on track, stay for a while, and come back.

Customers “don’t want to do one-off things,” Catchatore said. He observed that institutions, startups and businesses often want to fly three to six times a year. Biotechnology companies represent potentially advantageous markets as microgravity enables new materials, drugs and treatments, and these applications often require repeated design testing.

TechCrunch Events

San Francisco

|

October 27th-29th, 2025

So the orbital paradigm chose to build smaller capsules rather than the likes of the SpaceX dragons that fly astronauts and cargo to the International Space Station. “If you want to fly hundreds or thousands of kilograms, the customer is no longer a payload. That’s the destination you fly,” he explained.

The orbital return market is more crowded on both sides of the Atlantic. Varda Space Industries became the first company to nail commercial re-entry in 2024, but Europe’s The Exploration Company achieved controlled re-entry this summer with its own test vehicle.

American startups like Varda and Inversion Space have benefited from several unique tailwinds. In particular, the Department of Defense and other agencies often pour millions into over-testing and delivery demonstrations in the form of non-service funds, such as grants and contracts, where there is no need to waive a company’s ownership.

“We don’t understand that,” admitted Catchatore. “That’s one of the reasons we build to sell to our customers from the start, because otherwise we won’t go anywhere. We’re a little more hungry, so we have to be a little more athletic.”

The first launch is fast approaching. Orbital Paradigm will fly the Maiden mission in about three months using an unnamed launch provider carrying three customer payloads. The child will not recover. Instead, the target is to separate from the rocket, send data from orbit, withstand the intense heat and speed of cryogenic reentry, and drill a hole in the house at least once before the capsule collides in private areas.

“We designed the vehicle so that we didn’t have to land in a particular location,” he said due to cost and complexity.

The second mission in 2026 will feature a scaled kestrel with propulsion systems and parachutes, leading the capsule to the Azores Islands, where the Portuguese space agency is developing space ports. Like the first mission, there is no orbital facies. Just spend about 30 minutes firing and firing at microgravity before recovering – in this case the orbital paradigm can retrieve the vehicle and internal payload.

Cacciatore was proud of what the team had accomplished so far, but he had a clear look at the long road ahead. “We didn’t do much until we flew,” he said. “The words are good, but flying is the ultimate test.”

Source link