Srinagar, Kashmir – Afya’s *frail fingers choose the loose thread of her worn dark brown sweater while sitting in the urban rehabilitation ward of Indian Mairiah’s Kashmir main city, located at the edge of the bed of the rehabilitation ward of Sri Maharaja Hari Singh (SMHS) hospital.

Dressed in faded and dirty clothes hanging loosely over her thin frame, she said, “I’m not a fan of my heart.” Now I’m caught up in a nightmare, drugs are high, fighting for my life. ”

Afia, 24, is just one of thousands of people who are obsessed with heroin in conflict zones where drug addiction epidemics are consuming young lives.

A 2022 study by the School of Psychiatry at the Government Medical College of Srinagar found that Kashmir has overtaken Punjab, a northwest Indian state that has been battling the drug crisis for decades.

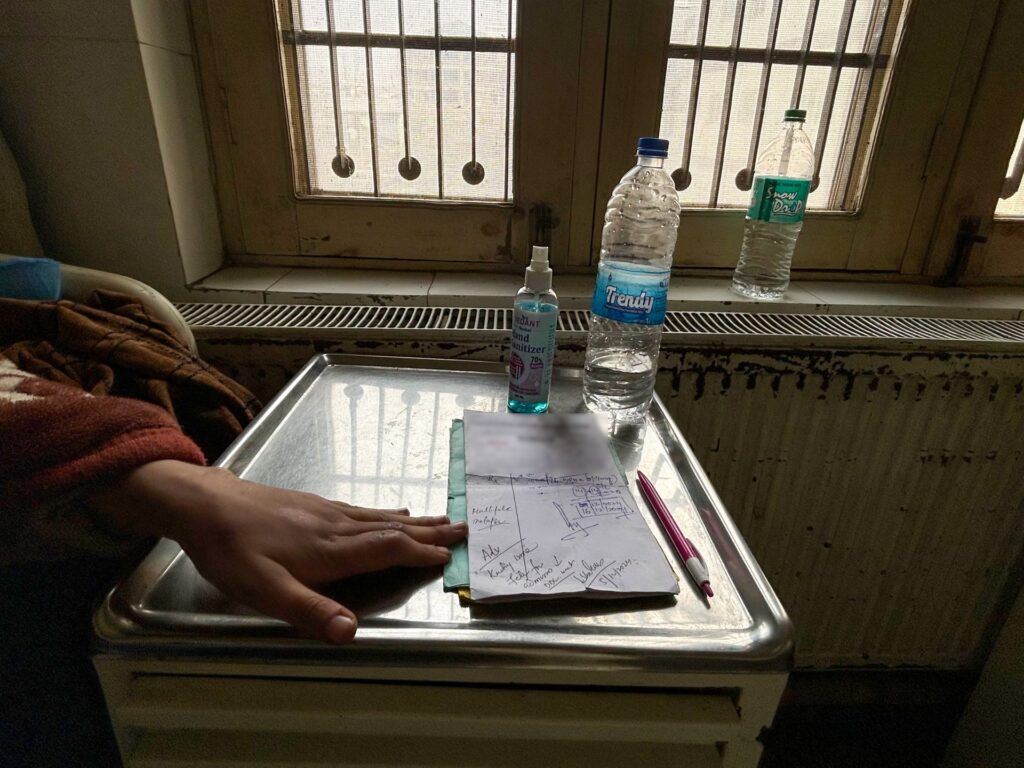

![SRINAGAR's SMHS Women's Addiction Treatment Ward [Muslim Rashid/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IMG_1510-copy-1740483637.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

In August 2023, a report from the Indian Congress estimated that nearly 1.35 million of Kashmir’s 12 million people were drug users, suggesting a sharp rise from around 350,000 users in the previous year, as estimated by a survey by the Institute of Mental Health (iMhans) of the Srinagar Medical College.

The Imhans survey found that 90% of drug users in Kashmir were between the ages of 17 and 33.

SMHS at Afiya Hospital participated in more than 41,000 drug-related patients in 2023. This meant that one person was brought in every 12 minutes, an average increase of 75% in 2021.

The surge in drug cases in Kashmir was fueled mainly in the proximity of the so-called “Golden Crescent,” an area that covers parts of neighbouring Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, where opium is grown on a large scale. Experts will also promote stress and despair following the COVID-19 pandemic, following the chronic unemployment caused by regions that lost partial autonomy in 2019, driving Kashmiri youth towards substance abuse.

As a result, Dr. Yasir, a professor of psychiatry at Imanns, hospitals and treatment centres, says it is from the local treatment centre. He said that although addiction treatment facilities have been set up throughout Kashmir since 2021, only a handful of hospitals are hospitalized for severe addiction patients like Afiya who require hospitalization.

“It looked harmless.”

“You’ll get through this,” Afia’s mother, Rabya* whispers, brushing the damp hair from her daughter’s face to the side. Afia has just taken a bath. Her father, Tabish*, sat in a corner chair, staring quietly.

Afia barely listens to her mother’s encouraging words and appears to be focusing on repeatedly removing the blue blankets offered by the hospital. The gaping wounds now bleed blood and thick yellow pus, warning that it could infect parents and attendants.

Over six years ago, Afia was a bright high school student dreaming of becoming a flight attendant. After passing through grade 12 with an impressive 85% mark, she responded to a job ad posted by a major private Indian airline.

“This is not the real me lying in this bed,” Afia tells Al Jazeera. “I was driving a car. I was a stylish woman known for her beautiful handwriting, intelligence and powerful communication skills. My quick memories made me stand out. I was able to easily remember the details. I was independent and confident.

“But now, as my brother said, I lie here motionlessly like a dead fish. Even they can’t ignore the smell that remains around me.”

She says she was chosen for an airline job and sent to New Delhi for training. “I stayed there for two months. It felt like a new beginning, a chance to fly, a runaway.”

But her rising dream was struck to the ground in August 2019 when the Indian government abolished Kashmir’s special status and imposed a months-long security lockdown to discourage street protests against the shock movement.

Thousands of people, including top politicians, have been arrested and thrown into prison. New Delhi has also halted its internet and other fundamental rights as it directly controlled the area for the first time in decades.

“The situation in my hometown was tough. I had no way of communicating with my family, nor had my phone call to know if it was safe. I couldn’t stay in New Delhi anymore and was cut off like that. I took a week’s holiday and went home,” Afia said.

When she left the capital with the help of other Kasimiris, she knew little about her journey as the flight attendants had ended even before it began.

“To the situation [in Kashmir] It was improved, the roads were opened and we could consider returning to New Delhi, but five months have passed. During that period, I lost my dream job and so I lost myself,” she says, raising her eyes well.

“I applied for a job with another airline, but nothing worked. Every time I refused, I started to lose hope. Then Covid Hit and Jobs became even more scarce. Over time, I lost interest in working completely – my mind wasn’t in it anymore. I didn’t want to do anything.”

Afia says that with each passing month, her frustration has turned into despair. She began to spend more time with her friends and sought comfort in their company.

“In the beginning we talked about struggle,” she says. “Then it started with a little seduction and there were very few cannabis puffs to deal with the tension. It seemed harmless. Then someone offered me foil. [of heroin]. I never thought about it again. I felt an euphoria. ”

“The only thing that gave me peace was drugs. Everything else felt like it was burning me from within.”

“Russian hunger”

But the escape was short-lived and she says the cycle of dependence took over.

“My dream quickly turned into a nightmare. Euphoria faded and replaced by ruthless hunger,” she says, explaining the hopeless measures and risks needed to find drugs.

“Once upon a time, I traveled 40km (25 miles) from Srinagar to the Shopian district of South Kashmir and met a drug dealer. My friend was out of stock and someone gave me his number. I called him directly to arrange the supply. He was a large dealer and at the time it was the only way we could get what we needed.

“When I got there, he introduced me to something called “Tichu.” [local slang for injection]. He was the first person to introduce drug infusions. He injected it into my belly right there in the car,” she says. “The rush was intense. It felt like heaven, but only for a second.”

That moment of happiness marked the beginning of her quick descent into deeper addiction.

“The grip of heroin is merciless. It’s not just drugs, it’s your life,” Afia says. “I woke up all night and adjusted with my friends to make sure it was enough the next day. It was tired, but the craving was stronger than all other types of pain.”

Heroin is the most commonly used drug in the region, and addicts spend thousands of rupees each month to buy it.

“Heroin is widespread and we see a large number of patients affected by it,” Imans says.

The professor has noticed an increase in drug abuse among women, and attributed it to mental health struggles and unemployment.

“Before 2016, there were rare cases involving heroin. Most people used cannabis or other soft substances. But heroin spreads like a virus and reaches everyone, including men, women, and even pregnant women,” he tells Al Jazeera. “Now we see between 300 and 400 patients every day, both new cases and follow-up, mostly involved in heroin addiction.”

But why heroin?

“Because of its rapid and intense euphoria,” he said, “many people found it more immediate and enjoyable compared to morphine.”

“It has the misconception that it is easy to use, has a higher potency and despite its highly addictive nature, it is safer or more refined than other drugs add to its appeal.”

“Wiring to find one last shot”

For addicts like Afia, who have been approved to rehabilitate five times so far, fighting heroin is a difficult battle every day.

“Every time I leave the hospital, my body pulls me back into the street,” she says. “It’s like my brain is wired to find the last shot.”

Afia’s intention to recover remains uncertain. She frequently left the hospital during rehabilitation for heroin or asked for it from other patients during daily walks in the hospital.

“Drug addicts have ways to connect with each other,” her mother Rabya tells Al Jazeera. “I once saw her talking to a male patient in English and realized that she wanted him for drugs.”

Rabya says she once found drugs hidden behind a woman’s toilet flush. “I found a stash and washed it off, but she [Afiya] I still managed to get it [heroin] Again,” she says. “She knows how to operate the system to get what she wants.”

The SHMS Rehabilitation nurse revealed how patients often fed security guards. “They give them money and give them excuses to make excuses even when they’re on medication,” the nurse says. The women’s ward is located near the entrance to the hospital – too, it makes it easier for patients to escape without being noticed, she says.

“It’s heartbreaking because we try to help, but some patients are just finding a way to leave.”

“she [Afiya] I ran away one night and came back the next day and spent hours with a male patient who helped me get some heroin,” the security guard says.

But Afia remains rebellious. “These drugs don’t bring about the peace you get from one shot of heroin,” she says Al Jazeera, her hands trembling and her nails dig into the hospital bed.

The physical blow to her body due to addiction is serious. An open wound of blood on her legs, arms and belly. When Dr Mukhtar A Thakur, a plastic surgeon at SMHS, first examined her, he said he was shocked.

“She was unable to walk due to deep wounds in her private parts and large wounds on her thighs. She had serious health issues, including damaged veins and infected wounds. Her liver, kidneys and heart were also affected. She struggled with amnesia, anxiety and painful withdrawal symptoms, putting her at a risk,” he says.

Afia’s parents say that taking her to rehabilitation at SMHS was a desperate move. “To protect her and her family’s reputation, we told relatives that she was being treated due to stomach problems and scars caused by the accident,” says Rabya.

“No one is married to a drug addict here,” she adds. “Our neighbors and relatives already have questions. They notice her wounds, her unstable appearance and repeated hospital visits.”

Afia’s father often hides her face in public, saying, “I can’t be embarrassed.”

Health experts say seeking treatment for drug addiction is a challenge for Kashmir women as social stigma and cultural taboos keep many women in the shadows.

“Women’s rehabilitation is often secretly done because families don’t want to know anyone. In Kashmir, everyone knows,” Dr Zoya Mir, a clinical psychologist who runs a clinic in Srinagar, told Al Jazeera.

“Many wealthy families send their daughters to other states for treatment, but others either suffer silence until it’s too late or delay treatment,” she says. “These women need compassion, not judgment, and only then can they begin to heal.”

*Name changed to protect your identity.

Source link