The browser does not support elements.

InThe Swedes, ready for Christmas, opened their mailboxes in anticipation of greeting cards, reminding them of the troubled times they live in instead. A 32-page pamphlet mailed to 5m households in the country urged citizens to consider how they would act if Sweden were attacked. “In Crisis or War” is full of practical advice. When an unspecified enemy stages the invasion: severe bleeding (puts firm pressure on the wound), reliable information (adjusted to public radio rather than social media), useful tips on nuclear fallout (which reduces radiation levels significantly after a few days) An illustration of a lonely Swedes sitting in a civil defensive shelter is returning home to the point that war is not just for others. It could be you one day. So, what are you going to do about it?

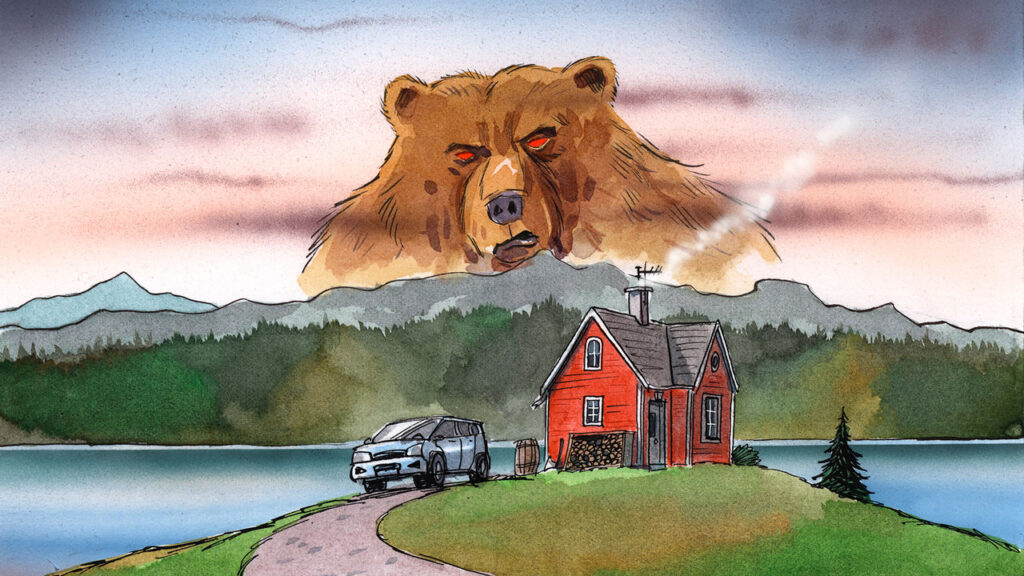

The purpose of the booklet is not to scare the citizens, but to shock the preparation. Households equipped with basic items will have less headaches for local governments to deal with at the time of an acute crisis, if they are needed to survive for days without external food, water, electricity, heating, or Netflix. Such “preparation” is a libertarian-type entertainment with cabins deep in the forest, a trend in conspiracy theory, a shotgun under the pillow, not to mention a pile of canned items. Recently, low-grade survivalism is considered a fundamental European civic duty. Nordic and Baltic countries have, with harsh winters, proximity to Russia, and somewhat temperamental tempers, and have, of course, led the way. Now the government is looking further south. France is preparing its own ending booklet for release by summer. On March 26, the European Commission issued a “preparation strategy” aimed at increasing society’s resilience through the shock of war and other crises. Just to be safe, it is officially recommended that citizens should stock up on 72 hours of food.

But what do you add to the ladder? All countries that issued guidelines have their own recommendations. Previously organized Switzerland offers a website that allows you to generate shopping lists for aspiring survivors based on family size and dietary preferences. Several items are reissued throughout Europe. Households need at least 2 liters of water per person per day for drinking alone, and are necessary for cooking and hygiene. As Sweden recommends, families of four who are aiming to survive in a week should store the best portion of 100 liters of water. Canned foods that can be stored without refrigeration and eaten without cooking are preferred over nasty gloves that require preparation (wartimes don’t seem to be the moment when you try the flashy soufflé you’ve been thinking of). It’s good to have a credit card on hand, but if your payment system breaks down, a week’s worth of shopping and tanking and car camping can help. The list continues: battery operated radio and flashlight, fire to keep you warm, first aid kit, duct tape, phone charger, spare glasses, iodine tablets, toilet paper, buckets to collect buckets, useful documents. Scandinavians can buy much of what they need with ready-made kits or create their own kits.

Not only will people tell us they will stockpile, but the preparation for national approval is intended to have a society satisfied with the right mental framework if the situation gets worse. The Swedes see it as part of the “total defense” of the realm. This is an unconscious homage to Italian football tactics. Finns talk about “comprehensive security” and are more agnostic about the causes of threats. A giant cybergliche may knock out electricity for several days. Natural disasters could block roads that supermarkets use to maintain shelves inventory. “Whether you’re preparing for a war or preparing for another crisis, the basic measures taken at the individual level will actually be pretty much the same,” says Petteri Kolbara, Secretary-General of the Finland Security Committee. Such a “overall” approach will help you sell this idea to countries far from Russia. Covid-19 was a useful reminder that people’s lives could suddenly change.

In particular, authorities want to promote the idea that protecting the territory is not just the work of soldiers and police. Businesses, community groups, and the wider public play a role in running society when stressed. A place that is resilient with a little preparation is less likely to be tested. Russian ships have no point “mistake” disconnecting Baltic power cables if the population is well equipped to deal with the outcome.

Even in Scandinavians, citizen scout-like instincts “prepare!” After the Cold War ended, they fell into anxiety. (The Swedish pamphlet is an update of advice that was first provided in 1943, repealed in 1991 and revived in 2018.) Just as peace dividends allowed the government to cut its defense budget, the public could stop thinking about the meaning of war. no longer. Germany is one of the places to build many new shelters (it’s still abundant in places like Switzerland and Finland). Conscription is considered across the continent. On March 7, Poland’s Prime Minister, Donald Task planned to allow all men to undergo some form of military training.

Stitching of time

Getting Europeans to be mentally prepared sends a broader, more calm message. There are limits to what the nation can do for its citizens. If one day a crisis hits, the public, used to being molykodor from cradle to grave for at least a while, may have to dodge itself.

Paying attention to the new mood, Charlemagne detoured to the supermarket to prepare his family for war. The cupboard below the stairs contains water next to the wine (which is also useful in the case of lockdown). The ladder is now bulging out with canned beans. The First Aid Kit has been updated. If that looks like an overkill, remember that the Finns say “you can prepare in advance.” ■

Economist subscribers can sign up for our opinion newsletter. This can connect our best leaders, columns, guest essays and reader communications.

Source link