This work was originally published in a city state.

Over the past year, I have been reporting on a Longform article in the Places Journal about the Rose Quarter Project in Portland, Oregon, the Biden administration’s most ambitious highway revision. The Marquee Project of the Reconnect Community Program places a four-acre cap on I-5 in the Lower Albina district, a historically black neighborhood that was devastated by the construction of highways and other city renewal projects in the 1960s.

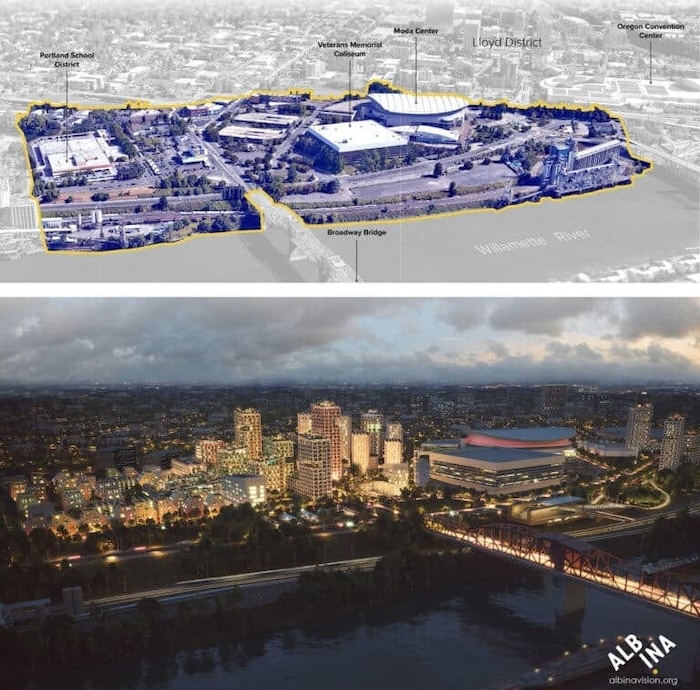

On all accounts, Oregon’s $450 million reconnected community grant was made possible thanks to the support of the Albina Vision Trust. Since its founding in 2017, the group has systematically built power, signed contracts with many of the area’s major landowners, invading in a 94-unit affordable residential complex and purchasing the buildings of the historic apartments next door. Covering the highway and eliminating dangerous off-ramps into the neighborhood is a prerequisite to making this area more liveable again.

The Albina Vision Trust’s plan to “buy back land, rebuild the community, and reaffirm Black heritage and Black Futures” was a perfect compliment for the Reconnected Community Program. Created for the “removal, remodeling or mitigation” of highways that divide neighborhoods through infrastructure investment and employment in 2021, the program was the first federal policy to specifically address racism that reached the construction of interstates. Transportation Director Pete Buttigigue regularly linked the program to racial justice in an official statement, prompting a lot of ock laughs from the conservative media.

However, for the Oregon Department of Transport, this reconnected community project is closely linked to the expansion of the underlying highway. It leads to years of protests and litigation that Portland environmental advocates have failed to comply. All of these various considerations and constituencies have made the Rose Quarter project extremely politically complex and expensive.

And now there’s another twist. Assuming an office, President Trump has issued executive orders in federal agencies that create conditions such as “racial justice” and “climate change” redundancy. As Trump continues to revoke Biden’s legacy as much as possible, Congressional Republicans are poised to eliminate the majority of funding for the “big beautiful bill” and the community program reunite. This leaves the entire program that funded the Rose Quarter project and the potentially transformative project from Buffalo to New Orleans.

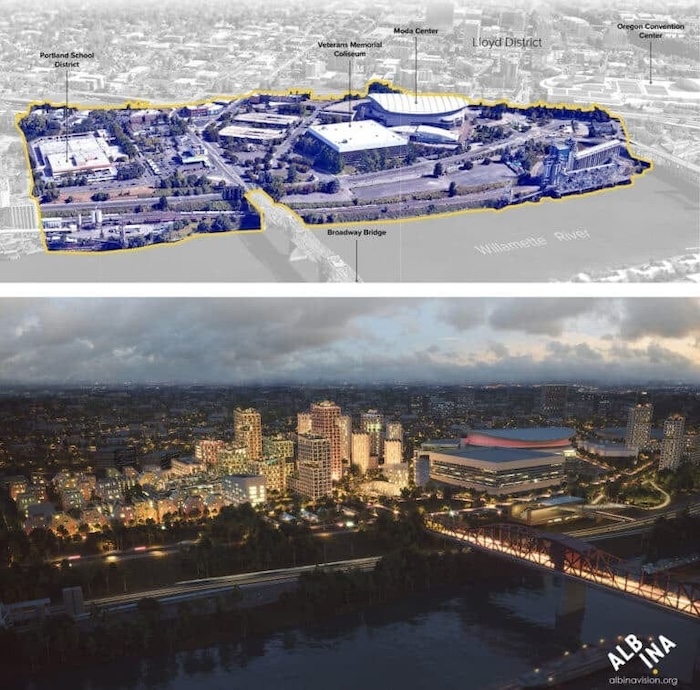

No matter what happens with the Rose Quarter Project, Albina Vision Trust’s work continues. The long-term plan is to build 3,000 mixed-income “climate-positive” homes on 94 acres across the river from downtown Portland. Their first building, Albina One, will begin welcoming residents this summer. Next up on the agenda is the redevelopment of the 10-acre Portland Public Schools Management Building. This is a brutal fortress that could become 1,000 homes.

The Albina Vision Trust’s “restorative redevelopment” model appears to be a promising extension of the new social housing movement tailored to American context. Cities are particularly relevant as they seek more intentional ways to rebuild public housing complexes and other places where the legacy of racist urban planning decisions is immensely looming. I’ll think about this a little more in future posts.

In the meantime, I would recommend reading my article in a rethinking of the Interstates series in Places Journal. This work goes deeper into the above story, linking this particular project to the history of American highway construction and highway removal. I also showcase many lovely people who have shown me around Portland and shared their hopes for the future of the city.

Source link