An mRNA-based vaccine for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) that has saved 2.5 million lives worldwide during the pandemic could help revitalize the immune system to fight cancer. This is a surprising finding from new research that we and our colleagues published in Nature.

While developing an mRNA vaccine for brain tumor patients in 2016, our team led by pediatric oncologist Elias Seyul discovered that mRNA can train the immune system to kill tumors, even if the mRNA is not associated with cancer.

you may like

So we looked at the clinical outcomes of more than 1,000 late-stage melanoma and lung cancer patients treated with a type of immunotherapy called immune checkpoint inhibitors. This treatment is a common approach that doctors use to train the immune system to kill cancer. This is done by blocking proteins that tumor cells make to turn off immune cell function, allowing the immune system to continue killing the cancer.

Of note, patients who received the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines within 100 days of starting immunotherapy were more than twice as likely to be alive three years later than those who did not receive either vaccine. Surprisingly, patients with tumors that generally do not respond well to immunotherapy also saw very large effects, with a nearly five-fold improvement in 3-year overall survival. This association between improved survival and COVID-19 mRNA vaccination remained strong even after controlling for factors such as disease severity and co-morbidities.

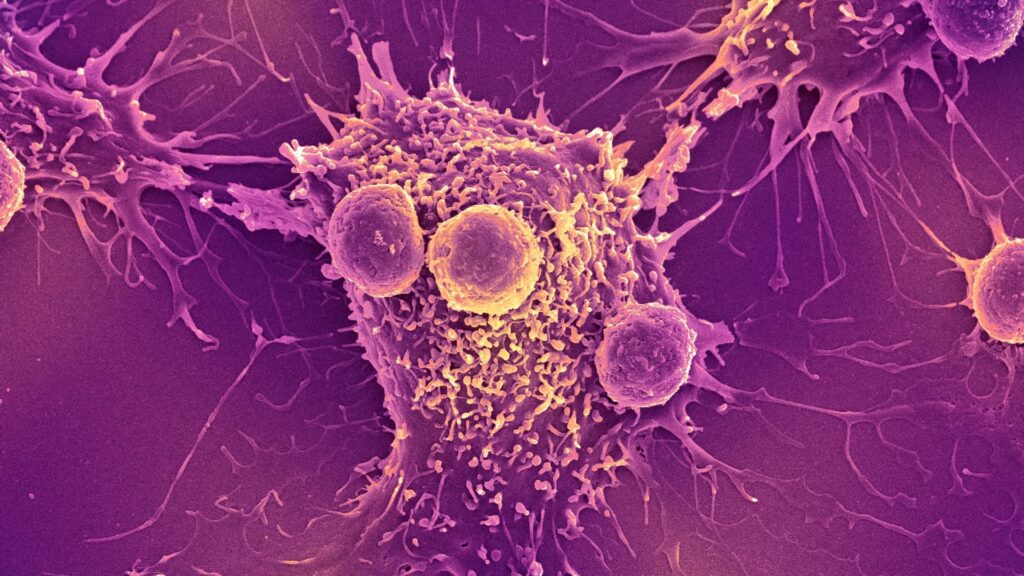

To understand the underlying mechanisms, we turned to animal models. We have discovered that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines act like an alarm, triggering the body’s immune system to recognize and kill tumor cells, overcoming cancer’s ability to turn off immune cells. Combining vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors can maximize the immune system’s ability to kill cancer cells.

watch on

why is it important

Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors has revolutionized cancer treatment over the past decade, providing cures for many patients previously thought to be incurable. However, these treatments are ineffective for patients with “cold” tumors that have successfully evaded immune detection.

Our findings suggest that mRNA vaccines may provide just the spark the immune system needs to make these “cold” tumors “hot.” If validated in our upcoming clinical trials, this widely available, low-cost intervention is expected to extend the benefits of immunotherapy to millions of patients who otherwise would not benefit from it.

What other research is being done?

Unlike infectious disease vaccines, which are used to prevent infection, therapeutic cancer vaccines are used to train a cancer patient’s immune system to fight tumors more effectively.

We and many others are currently working hard to develop personalized mRNA vaccines for cancer patients. This involves taking a small sample of a patient’s tumor and using machine learning algorithms to predict which proteins within the tumor would be the best targets for a vaccine. However, this approach can be costly and difficult to manufacture.

you may like

In contrast, mRNA COVID-19 vaccines do not require personalization, are already widely available around the world at low or no cost, and can be administered at any time during a patient’s treatment. Our finding that a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine has substantial antitumor efficacy offers hope that it may help extend the anticancer effects of mRNA vaccines to everyone.

what’s next

In pursuit of this goal, we are preparing to test this treatment strategy in patients in a nationwide clinical trial for patients with lung cancer. People receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors will be randomly assigned to receive or not receive a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine during treatment.

This study will determine whether a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine should be included as part of standard treatment for patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ultimately, we hope this approach will help many patients treated with immunotherapy, especially those who currently lack effective treatment options.

This study demonstrates that a tool born of a global pandemic could become a new weapon against cancer, rapidly expanding the benefits of existing treatments to millions of patients. By leveraging familiar vaccines in new ways, we hope to extend the life-saving benefits of immunotherapy to cancer patients who have been left behind.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link