In 1987, a worker lights a cigarette next to a new well near the village of Bourakebugou in Mali.

But at that moment, an explosion echoed inside the well. We now know this is due to a previously undetected cloud of flammable hydrogen wafting from a gas reservoir below the hole.

you may like

The Boora Kebugou well is the world’s first and only well capable of producing hydrogen. When mixed with oxygen in a fuel cell, hydrogen, the smallest and simplest molecule in existence, can generate electricity with no greenhouse gas emissions and only heat and water as byproducts. This makes hydrogen a clean energy source, with demand expected to increase fivefold by 2050 for the production of microelectronics, supplying industry, and powering cars and buildings.

Resource exploration companies are currently racing to discover reserves of natural hydrogen, also known as “gold” hydrogen. To help them, scientists have identified the key “ingredients” necessary to form such deposits. And thanks to this knowledge, technologies that accelerate or mimic natural hydrogen production, once thought to be unfeasible, are gaining traction, experts told Live Science.

“The more you start looking, the more you keep finding,” Jeffrey Ellis, a petroleum geochemist with the U.S. Geological Survey, told Live Science.

paradigm shift

Hydrogen is an energy source, but it’s also an important ingredient in fertilizers, refined oil, and rocket fuel. In industry, nearly all hydrogen is produced by heating natural gas with steam to form a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, from which hydrogen is extracted.

This method produces “grey” hydrogen and releases about 1 billion tons (920 million tons) of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year. This is equivalent to 2.4% of global annual emissions. In theory, renewable energy could replace natural gas to produce “green” hydrogen, but while “blue” hydrogen is produced from fossil fuels, no carbon is emitted into the atmosphere. However, these together account for only a small portion of the world’s hydrogen production.

“Hydrogen is a clean energy source, but how we get it is important,” Chris Valentine, professor of geochemistry at the University of Oxford, told Live Science.

you may like

But new hydrogen sources could reduce the industry’s carbon footprint, as it turns out that large amounts of hydrogen can accumulate underground. Scientists have long known that rocks in the Earth’s crust produce hydrogen, but experts previously concluded that the gas could not collect in reservoirs because hydrogen was detected in very small amounts in oil and gas wells.

The discovery in Mali overturns that theory. Researchers have found that the places where companies drill for oil and gas are not the best places to find hydrogen.

A huge reservoir waiting to be discovered

The discovery in Mali has begun a global search for hydrogen reservoirs. But before starting expensive exploration projects, geologists need to know how much hydrogen is lurking underground.

New estimates say the amount is staggering. Over the past billion years, Earth’s continental crust has produced enough hydrogen to meet society’s current energy needs for 170,000 years, a recent study by Valentine and colleagues found. Much of this hydrogen has escaped into the atmosphere, but the numbers are “a starting point for understanding the importance of hydrogen production in the Earth’s crust,” Valentine said.

Other estimates are twice the number in the Valentine paper. Ophiolites are chunks of oceanic crust that jut out from continental crust, and some estimates suggest that these oceanic crust remnants could produce as much hydrogen as continental crust, Valentine said.

But how much of this hydrogen remains in the Earth’s crust? In 2024, Ellis and his colleagues calculated that there will be 6.2 trillion tons (5.6 trillion tons) of hydrogen on Earth. This is about 26 times the amount of oil known to be left in the ground. It is largely unknown where these hydrogen stocks are located. While most is likely too deep or offshore to be accessed, and some reservoirs may be too small to be worth extracting, the researchers stressed that just 2% of total hydrogen could displace current fossil fuels for 200 years.

“The potential there is huge,” Ellis said. Additionally, natural hydrogen, unlike the type created through industrial processes, exists in the Earth’s crust and therefore has built-in storage. Ellis said the carbon footprint is much smaller than produced hydrogen, and emissions only come from extraction.

component

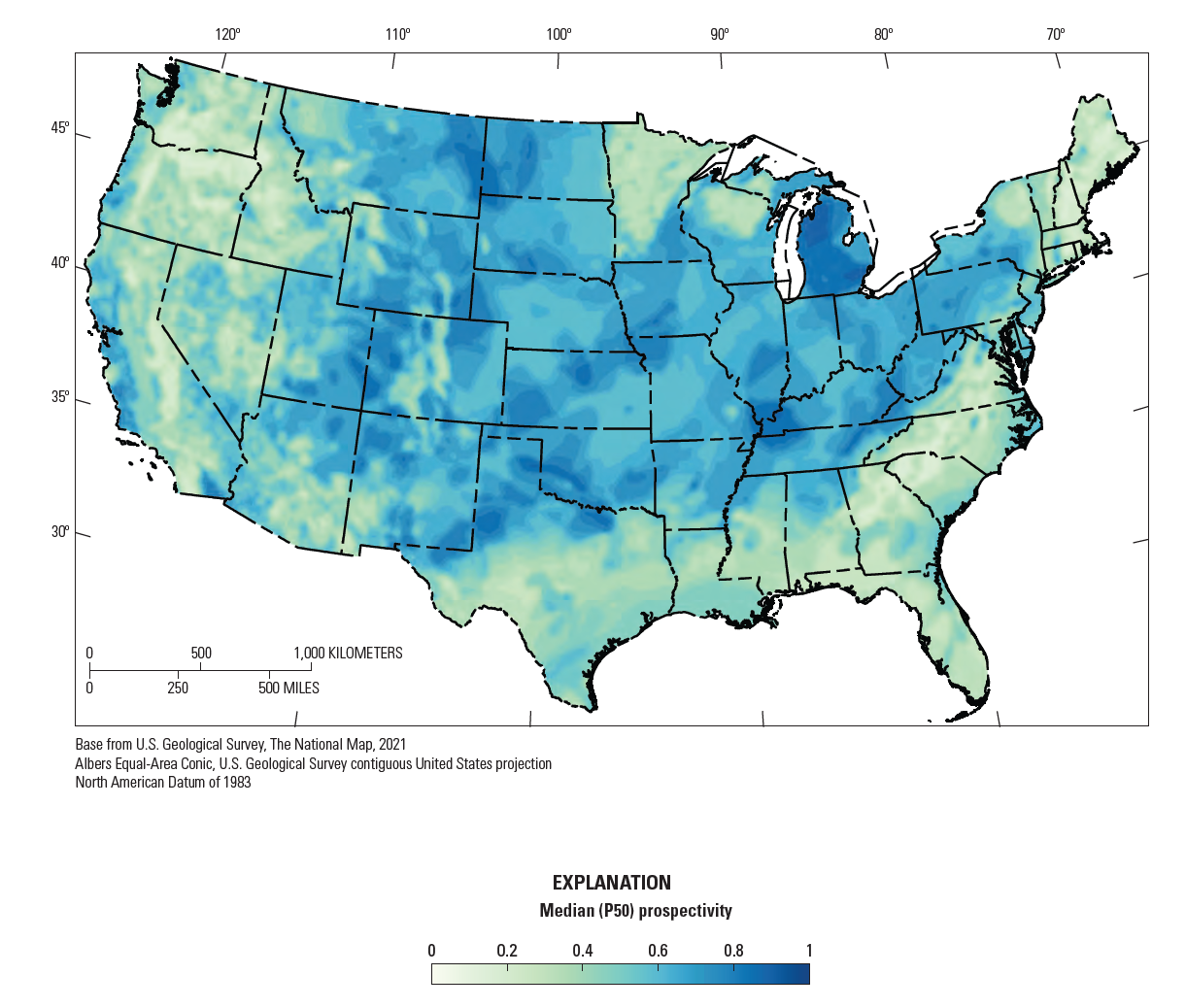

In January 2025, Ellis and his colleagues released a map showing where hydrogen storage sites are likely to exist in the lower 48 states of the United States. The researchers used gravity and magnetic signal data to estimate the composition of rocks throughout the Earth’s crust and determine where the hydrogen migrated underground.

“This was the first time we had attempted this kind of mapping exercise,” Ellis said.

The researchers estimated the potential for productive hydrogen reservoirs, known as prospects, based on six geological requirements for producing and capturing hydrogen within the Earth’s crust. On the map, the line of sight ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 means hydrogen is most likely not present and 1 means hydrogen is very likely present.

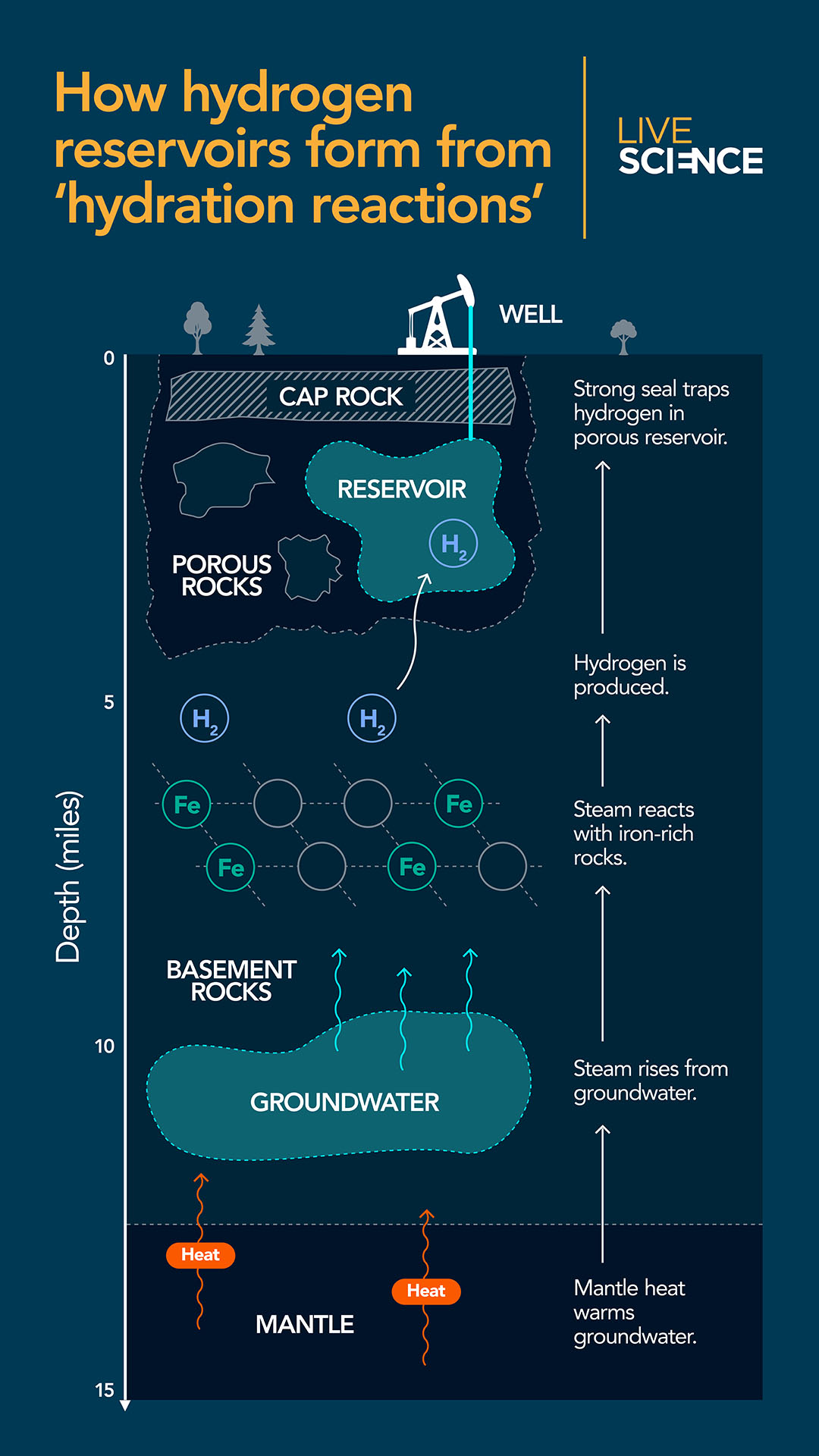

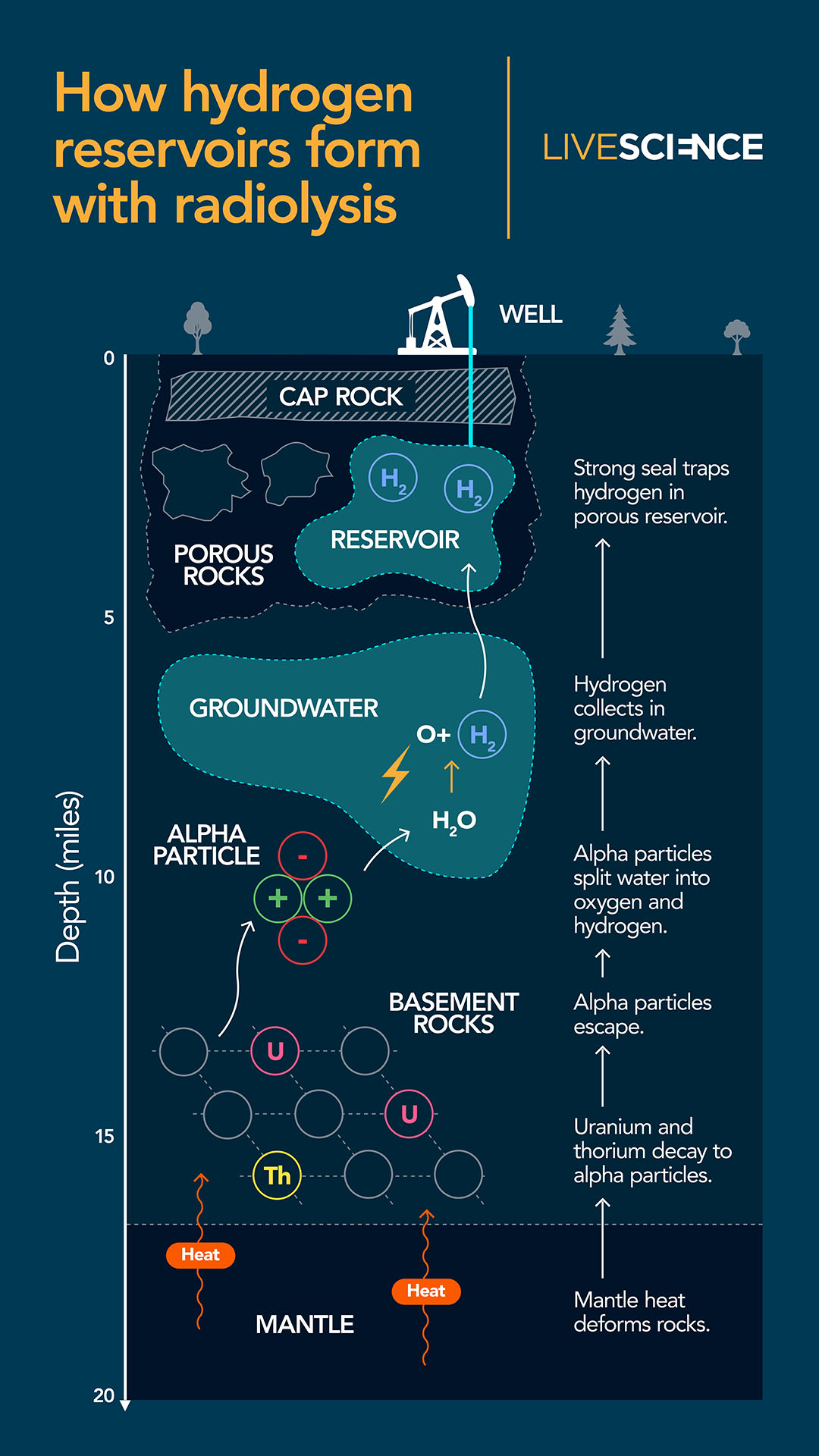

To form a hydrogen reservoir, the first and second requirements are the presence of abundant groundwater and hydrogen-producing rocks in the area. Oliver Waugh, an assistant professor of geochemistry at the University of Ottawa, told Live Science that water requirements limit hydrogen production to the top 10 miles (16 kilometers) of the Earth’s crust.

The best hydrogen-producing rocks are iron-rich rocks, which produce hydrogen through a “hydration reaction” in which water and rocks react. Other good sources of hydrogen include rocks rich in uranium and thorium, which produce alpha particles when the radioactive elements decay. These alpha particles can split water into oxygen and hydrogen, a process known as radiolysis, Waugh said.

Rocks rich in iron include basalt and gabbro. The Earth’s mantle, the layer beneath the Earth’s crust, heats groundwater, producing steam that reacts with iron to produce hydrogen. Rocks rich in uranium and thorium include granite, which can cause radiolysis of water.

The third requirement is that the source rock be very hot, 480 to 570 degrees Fahrenheit (250 to 300 degrees Celsius), which ensures a fast reaction rate, Ellis said.

Fourth, the region must have reservoir rocks that can hold the hydrogen after it is produced and moves through the Earth’s crust. Ellis said the reservoir rock is typically porous sandstone, but other rock types can be used as long as they are highly fragmented.

The fifth criterion for forming a hydrogen reservoir is an impermeable “seal” to confine the gas within the reservoir. “Something like shale or something like salt would be really ideal on top of a porous rock,” Ellis says. Importantly, the seal must be present when the hydrogen is produced, or the gas will escape into the atmosphere, he said.

The sixth and final condition is that microbial activity is minimized where hydrogen is produced and accumulated, since microbes consume hydrogen, Waugh said.

According to Valentine, these six conditions, or ingredients, occur on every continent. Currently, hydrogen companies are primarily drilling exploratory wells in the Midcontinent Rift, where the North American continent began to break apart a billion years ago and ultimately failed to break apart, where iron-rich rocks are abundant.

Looking to the future

Researchers are also investigating hydrogen deposits in Oman, where ophiolites are present. Ellis said geologists at the University of Colorado are conducting a pilot project to test the feasibility of producing “induced hydrogen” domestically.

Stimulated hydrogen production is inspired by what scientists have learned about the geology that produces and stores hydrogen. This involves injecting water into the Earth’s crust to initiate either hydration reactions or radiolysis.

A year ago, Ellis said, people in the hydrogen industry were skeptical that accelerating hydrogen production would ever happen. But now, “we’ve seen a big change,” he said.

If natural hydrogen can be found and extracted, the gas has the potential to reduce emissions in a wide range of sectors. For example, abundant hydrogen has been discovered in mines, and since this is where humans drill deepest into the Earth’s crust, the gas could power mining operations, Waugh said.

Natural hydrogen could also reduce emissions from industries such as fertilizer production. “If we can replace hydrogen produced from hydrocarbons with clean hydrogen, we can make a huge difference very quickly,” Valentine said.

Natural hydrogen will not solve the climate crisis, but it can reduce some of the risks. “It has to be one of many strategies,” Waugh said. “All we need is to understand its true potential and how to make the most of it.”

Some important considerations for companies are whether the benefits of developing natural hydrogen storage, if found, are worth the costs of building on-site production plants and transporting the gas to industries that need it.

“Even if you are in a remote area and find a very large gas field, it may not be worth producing it because the cost of bringing hydrogen to market is too high,” Valentine said. “There’s a trade-off.”

But overall, experts are optimistic. “I think there are about a dozen wells being drilled in the U.S. right now,” Ellis said. “They discovered a lot of hydrogen.”

Source link