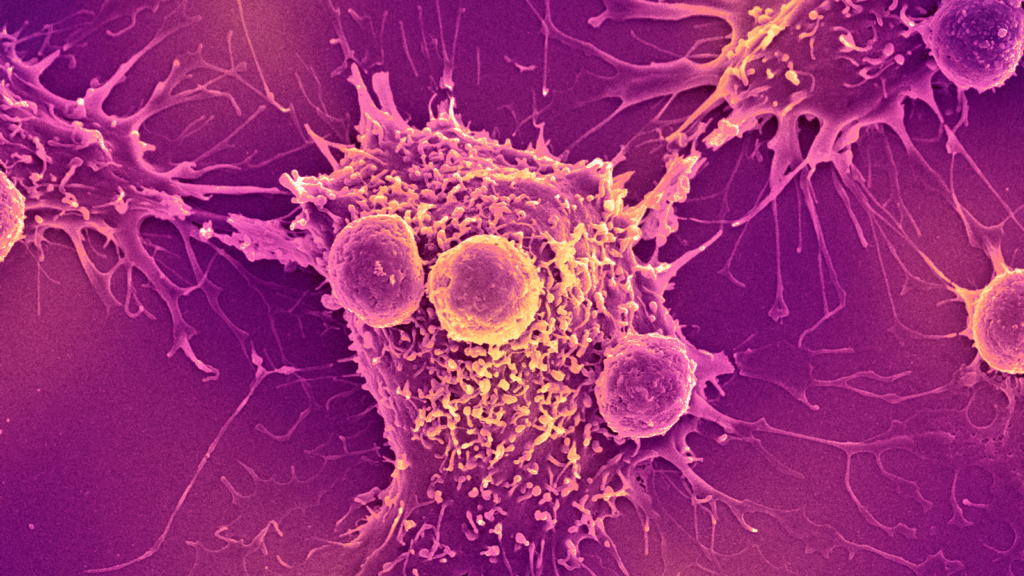

Universal cancer vaccines under development may help revive the immune system against tumors and outweigh the effects of existing cancer treatments, animal studies suggest.

Like vaccines for viral infections such as influenza, many cancer vaccines are designed to help the immune system recognize certain proteins. However, while traditional vaccines aim to prevent disease, cancer vaccines are currently being developed to help remove cancers that are already growing in the body and prevent the cancers that have been treated from returning.

Nevertheless, traditional vaccines and cancer vaccines often work in the same way. Influenza shots train the immune system to look for unique proteins found on the surface of influenza viruses, but cancer vaccines usually teach immune cells to find unique features of cancer cells.

You might like it

However, there is a challenge. These oncoproteins of interest may often be unique to individual patients. This means that each cancer vaccine may need to be formulated specifically for each patient. It is possible to create such a personalized vaccine, but they take time to make it – and, tentatively, the cancer of the patient may mutate and the vaccine may be less effective.

“It can take several months from when a patient specimen is actually undergoing personalized therapy,” said Elias Sayle, a pediatric oncologist at the University of Florida Health. Sayour and colleagues wondered whether a cancer vaccine could be designed that didn’t require this personalization and would instead fire a common immune response to maintain cancer.

“The idea that something could be quickly available, although in a non-specific way, could be innovative in how we bridge therapy and manage patients,” Sayou told Live Science.

Related: New mRNA vaccines for fatal brain tumors trigger strong immune responses

“Ready-made” cancer vaccine

The experimental vaccine, described in a report published on July 18th in Nature Biomedical Engineering on July 18th, is built on Messenger RNA (mRNA), which also formed the basis for the first Covid-19 vaccine that is currently being updated.

mRNA serves as a blueprint for cells to form the basis of new proteins. In the Covid-19 vaccine, the molecule contains a little instruction for the coronavirus. New cancer vaccines have instructions for substances that increase the body’s first-line immune defense, venting the “natural” immune system rather than “adaptive.”

In particular, vaccines aim to promote the body’s production of immune messengers, which play an important role in controlling inflammation and exploring spots in cancerous tumors. In a series of experiments in lab mice, researchers demonstrated that this signaling is key to tumor removal early in development. This signal brings together the immune system to attack tumors, preventing tumor growth. Blocking them will interfere with tumor growth.

Furthermore, these experiments showed that this early interferon activity is essential for a common form of cancer treatment called immune checkpoint inhibitors. These treatments tear the breakdown of immune cells, thus maintaining high levels of activity and effectively killing cancer.

Cancer involves hijacking interferon signals and interfering with subsequent anti-cancer immune responses. Therefore, cancer vaccines act as a kind of immune “reset.”

Researchers used the vaccine in combination with checkpoint inhibitors in a mouse model of melanoma, a type of skin cancer. In mice with treatment-resistant tumors, the treatment combo worked better than just checkpoint inhibitors, the team found. They also independently tested vaccines in mouse models of other cancers, including gliomas (brain tumors) and pulmonary osteosarcoma (bone cancer that spreads to the lungs). Similarly, when applied in its own right, it showed promising anticancer effects.

For this early work, the team tested several different mRNA formulations to agitate the interferon reaction, discovering that each of them did so effectively. More work is needed to understand whether the mRNA molecule itself or the protein used to make it is more important to trigger this generalized reaction, Sayou noted.

The current study focuses on solid tumors and is more likely to be resistant to immunotherapy than blood cancer, Sayou said. But “I personally think this can be used for all forms of cancer,” he added. “I think this is a universal paradigm that can be used to treat cancer.” In particular, he was able to see it being applied as a secondary prevention, helping to stop the treated cancer from returning.

“This exciting and novel paper provides promising evidence that giving the immune system a short, targeted boost at the right time will help previously unresponsive tumors respond to immunotherapy,” said Diana Azam, associate professor and director of science at the Center for Advanced Cancer Treatment at Florida International University.

“This approach can be particularly useful for ‘cold’ tumors. This is a type of cancer that does not trigger a strong immune response, such as the pancreas, ovaries, and some breast cancer.’ These tumors are hidden from the immune system and can be difficult to target with immunotherapy, so this type of vaccine may help expose these cancers to attack.

“While more research is needed to see how well this approach works for people, the results of mouse encouragement provide a strong foundation,” Azam said. People will want to ensure that vaccines incorporate useful immune responses without causing unnecessary inflammation in the long run, for example. “Future research will address key questions about safety, consistency and long-term efficacy in real-world cancer patients,” she concluded.

Meanwhile, Sayour and his colleagues have begun human exams to test the two-hit approach. It’s a ready-made cancer vaccine followed by a personalized vaccine. They work with patients with two types of recurrent cancer: either glioma or osteosarcoma in children.

“This approach saves the precious time needed for personalized vaccinations and can induce rapid immunity that could be further seized by personalized therapy,” Sayou said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide medical advice.

Source link