Scientists can determine how aging the whole body is based on a single snapshot of the brain, researchers argue in a new study.

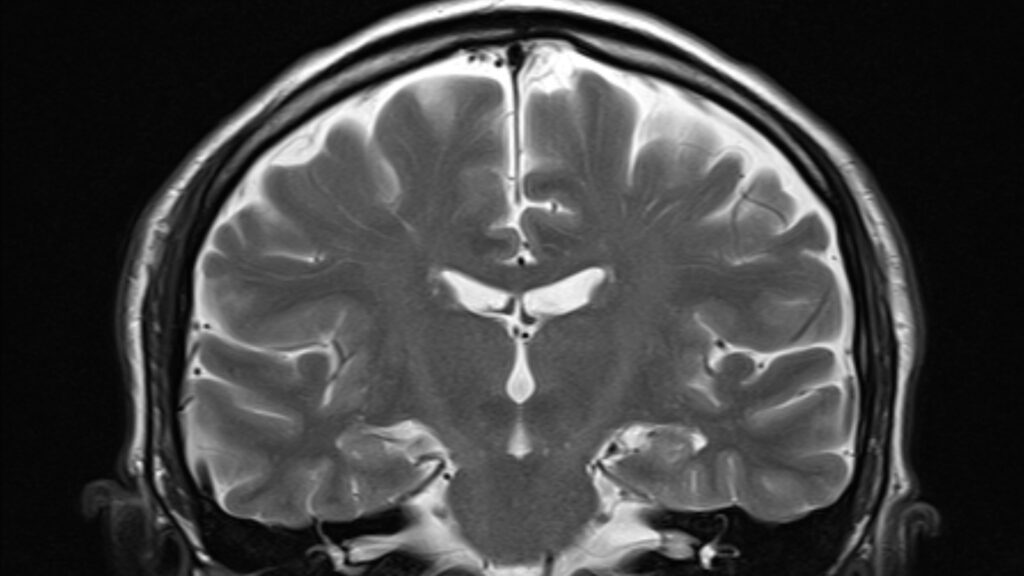

Scientists who published their findings in the journal Nature Aging on July 1st developed a benchmark for biological aging based on brain MRI. The team says the tool can predict future risks for individuals with cognitive impairment and dementia, chronic conditions such as heart disease, physical frailty and early death.

Ahmad Hariri, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, said: “Faster aging increases the risk of many diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and dementia,” he told Live Science via email.

You might like it

Hariri and her colleagues used data from the Dunedin study, which lasted 1,037 people from birth to middle age in Dunedin, New Zealand. Born in 1972 and 1973, these participants received regular 19 ratings to check the function of the heart, brain, liver, and kidneys.

To develop the tool, the team analyzed brain MRIs taken from this cohort at age 45 and performed data on brain structure (volumes of various brain regions and the ratios of white and gray matter through machine learning algorithms.

They compared processed brain data with other data collected simultaneously from participants, including physical and cognitive decline, subjective health conditions, and signs of facial aging, such as wrinkles. They argued that the significant reduction in these areas is linked to a faster pace in which aging, overall, and brain data features correlate with those metrics. They called the resulting model “Dunnedin pace of aging calculated from neuroimaging” or Duny Dinpakuni.

Related: Epigenetics Related to the Maximum Lifespan of Mammals

Previously, the team created a similar tool called Dunedin Pace for Aging, calculated from the epigenome (Dunedinpace). The metrics looked at methylation (chemical tags attached to DNA molecules) in blood samples to estimate the pace of people’s aging. Methylation is a type of “epigenetic change,” meaning changing gene activity without altering the underlying code of DNA.

“[DunedinPACE] “Dunedinpacni now allows research without epigenetic data, but found similar results using brain MRI to measure accelerated aging.

To see if their new tool would be useful to anyone other than Dunedin, the team will use it to estimate the pace of aging using MRI on other datasets: 42,000 MRI from Biobank, UK. More than 1,700 MRIs from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI); 369 in the Brainlat set, which contains data from five South American countries.

“Generalizing findings across datasets and demographic groups is a major priority for brain imaging research,” Duke PhD student Ethan Whitman told Live Science in an email.

They found that Dunedinpacni also estimated the aging rate of these other cohorts as well as other measures used in the past.

The UK biobank and ADNI also include measurements of specific health benefits of aging, including tests of physical frailty, grip strength and walking speed, such as heart attacks, strokes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and death from any cause in the cohort. Using these additional measures, the team was able to link faster aging rates, increasing the risk of heart attacks, stroke, COPD, and death, as determined by Dunedinpacni.

Hariri believes that the types of MRI used by Dunedinpacni are collected on a daily basis and therefore may be widely adopted. Now it’s the question of calculating data and determining criteria for what reflects “health” and “poor” aging, he said.

“They’re not involved in the research,” said Dr. Dan Henderson, a primary care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a medical instructor at Harvard Medical School who was not involved in the research. “It is worth considering other data sets where genetic and other factors may differ in important ways,” he added.

Henderson said that it can be seen that Dunedinpacni is ultimately used instead of traditional health measures to fine-tune medical interventions for individual patients. Whitman also sees broad meaning in his research. Assuming that doctors’ use has been tested, he believes it will help prepare patients for age-related health issues before they appear.

“We were really surprised that our tools could predict the risk of disease before symptoms begin,” Whitman told Live Science in an email. “I think this is a great example of why studying aging is important in general, but especially in young and healthy people. If you’re just studying people after getting sick, you’re missing out on a lot of things.”

Brain Quiz: Test your knowledge of the most complex organs in your body

Source link